Reporters Without Borders’s 2021 “Press freedom predators” gallery focused on "old tyrants, two women and a European" amongst the 37 listed, but missed highlighting a troika led by Havana included in the list.

Hispanic America's troika of press freedom predators: Daniel Ortega, Nicolas Maduro and Miguel Díaz-Canel

In the 1990s when the Cuban economy was collapsing following the withdrawal of Soviet aid, the Clinton administration believed that the greatest threat posed by Cuba was regime change, or a collapse of the dictatorship that would lead to a mass exodus of millions of Cubans, and sought a soft landing. The Castro regime had a different idea. In 1990 following a request made by Fidel Castro to Lula Da Silva the Sao Paulo Forum (FSP) was established with the goal “to reconquer in Latin America all that we lost in East Europe.” Thirty years later with Venezuela and Nicaragua imploding under Marxist dictatorships, restricting speech copying the Cuba model, assisted by spies and troops of the Castro regime, the foolishness of the 1990s American assessment of the Castro regime should be evident. Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela, Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, joined together by Raul Castro's hand picked president, Miguel Díaz-Canel, represent a troika of press freedom predators identified by Reporters Without Borders. The expansion of this model from Cuba to both Venezuela and Nicaragua have other impacts in the region, and on the United States.

Juan Carlos and Amanda Gahona, the brother and mother of journalist Ángel Gahona, Photograph: Diana Ulloa/AFP/Getty Images

Consider the 2018 protests in Nicaragua where "hundreds of government opponents were killed by police and other Ortega enforcers"; they were "helped by Cuban agents," reported Mary O'Grady in The Wall Street Journal on June 13, 2021. One of those killed was Nicaraguan journalist Ángel Gahona who was "live-streaming a protest against President Daniel Ortega when he was shot dead. His family believe the aim was to silence him," reported The Guardian on May 29, 2018. The Nicaraguan newspaper "La Prensa" reported on June 3, 2019 that up 200 Cuban "intelligence officers" are operating in Nicaragua and in addition to other activities are carrying out "training programs for Ortega’s Police, Migration and Immigration authorities, Customs and prison system officials." They are giving trainings in "repressive tactics, espionage and control of prisons and border posts." Cuban spies have been openly operating in Nicaragua since 2007 with Daniel Ortega's return to power in 2006.

Nicaragua has a population of 6.6 million, and rising repression has led to an increase in migration to neighboring Costa Rica creating strains in the Central American democracy while other refugees have made the long trek to the United States. President Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua is identified as a "press freedom predator", but the role of the Castro regime in training the Nicaraguan despot and his security forces is left out.

Reporters José Carmelo Bislick Acosta and Andrés Eloy Nieves Zacarías shot dead in Venezuela. Source: RSF, Twitter

The Cuban government since 1959 has had a vision that can be fairly described as imperialist. The Castro regime repeatedly attempted (and continues to attempt) to subvert and destroy democratic governments, such as Romulo Betancourt's social democracy in Venezuela with armed guerillas throughout the 1960s, that failed and later succeeded with Hugo Chavez through the ballot box in 1998 and continued since 2013 with Nicolas Maduro. It has been imperialist in the sense that these governments have been managed by Havana's military and intelligence apparatus, and provides the Castro dictatorship with raw materials, and national wealth in exchange.

Angus Berwick in the August 22, 2019 Reuters, "Special Report: How Cuba taught Venezuela to quash military dissent" reported that the governments of Cuba and Venezuela signed two agreements, documents reviewed by the news agency, in May 2008, that gave Cuba’s armed forces and intelligence services wide latitude in the South American country to:

Train soldiers in Venezuela

Review and restructure parts of the Venezuelan military

Train Venezuelan intelligence agents in Havana

And change the intelligence service’s mission from spying on foreign rivals to surveilling the country’s own soldiers, officers, and even senior commanders.

Havana Times reported on December 8, 2018 that the Organization of American States Secretary General, Luis Almagro, "assured that there has been a 'Cuban presence' in tortures committed in Venezuela. 'It is estimated that the Cuban presence in Venezuela is 46,000 people, an occupation force that teaches to torture, to repress, to do intelligence tasks, civil documentation, migration.'"

The online independent Venezuelan publication La Razon, reported on June 26, 2021 that the Casla Institute, a Czech based NGO with a mission "to share with Latin-American reformers the finest lessons of democratic and economic transformation in post-communist Europe." The Casla Institute's 2021 report on Venezuela presents testimonies from civilians and soldiers who were tortured by Cuban officials, and a rape was also reported. These cases were referred to the International Criminal Court. The institute denounces that Cuban officials routinely participate in torture against Venezuelan civilians and members of the military. The Casla Institute study documented 25 incidents where 141 people were victims in 2020 of arbitrary detention, torture, forced disappearance and sexual violence.

The violence is also visited on journalists, and family members of media owners.

The Committee to Protect Journalists denounced that on "August 17, 2020, four armed men kidnapped radio show host José Carmelo Bislick Acosta; his bullet-riddled body was found the next day in a vacant lot near his home in the eastern Venezuelan city of Güiria, according to news reports and the Caracas-based free press organization Espacio Público." He was a member of the ruling party, but sometimes "criticized Venezuela's socialist revolution," according to Mónica Salazar, general secretary of the National Journalists Association in Sucre state, which includes Güiria.

Reporters Without Borders on August 25, 2020 also reported on Bislick Acosta's killing, and the killing of another journalist days later. Journalist Andrés Eloy Nieves Zacarías was shot dead "when at least 10 heavily-armed members of Venezuela’s Special Action Forces (FAES) burst into the recording studio of La Guacamaya TV, a local TV station located in the home of the station’s director, Frankie Torres, in Cabimas, in the northwestern state of Zulia, [on August 21, 2020]. They also shot dead Torres’ son, Víctor Torres. A few hours after the raid, the FAES said the two victims were members of a “criminal gang” – a claim immediately denied by the families of the victims."

President Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela is identified as a "press freedom predator", but the role of the Castro regime in training the Venezuelan despot and his security forces is left out.

Venezuela had a population of 30 million, but in 2015 years of socialist centralized planning and government repression reached critical mass, and an unprecedented exodus began from the South American nation that has dwarfed anything else in Latin American history. According to The Guardian "more than 5.6 million have left the country since 2015," and this mass emigration is being felt in the United States.

Jorge C. Carrasco, a journalist based in Brazil, writing in Foreign Policy in May 2019 concluded that "Venezuelan Democracy Was Strangled by Cuba" by "decades of infiltration" that "helped ruin a once-prosperous nation."

The Biden administration in March 2021 added Venezuelans "to the list of people eligible for Temporary Protected Status, a program that gives immigrants from select countries time-limited permission to live and work in the United States", and they have been allotted 323,000 spots. Joshua Goodman writing for NBC reported on June 28, 2021 "Record Numbers of Venezuelans Cross the U.S.-Mexico Border as Overall Migration Swells" and that "they're bankers, doctors and engineers from Venezuela, and they're arriving in record numbers as they flee turmoil."

The model that both these regimes are based on is the Castro regime in Cuba. The Castro brothers took power on January 1, 1959 in Cuba and began a process of consolidating dictatorial power. This included outlawing opposition political parties, ending academic freedom, and taking over the media.

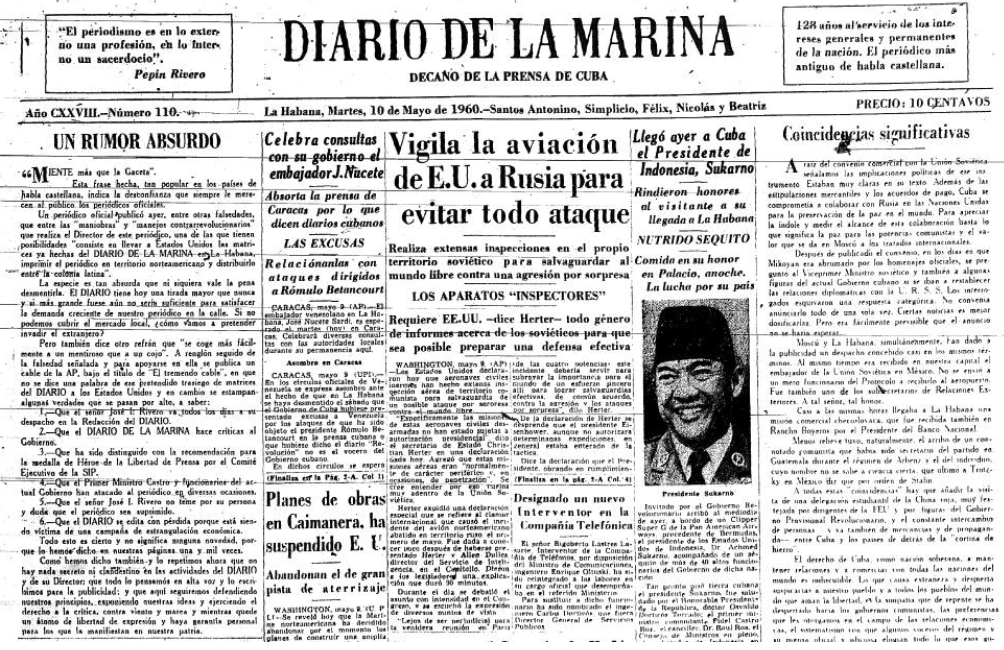

May 10, 1960 issue of the Diario de la Marina. It was closed on May 12, 1960 after 128 years.

At the University of Havana, and the already controlled Federation of University Students, FEU, held a mock burial of the Diario de la Marina newspaper. [ Fidel Castro had personally intervened in the student elections against the popular leader Pedro Luis Boitel, because they did not like his democratic convictions]

On May 12, 1960—the Diario de la Marina newspaper was closed, ending its 128 year history. Humberto Medrano, deputy editor of Prensa Libre, the newspaper with the largest circulation in Cuba, published a text the following day:

It is painful to witness the funeral of freedom of thought in a center dedicated to culture […] Because what was buried last night [at the University] was not a newspaper. Freedom of thought and expression were symbolically buried. The obligatory climax of that act has been the comment of the newspaper Revolution. The title of that comment says it all: "Free Press on the way to La Marina." They didn't have to say it. Everybody knows.

Prensa Libre was attacked by a mob then shut down days later on May 16, 1960. Prensa Libre's and La Marina’s offices and equipment were confiscated by the dictatorship and used to publish its dictatorship controlled newspapers.

March 1960 issue of Prensa Libre.

Cuba's last non-government controlled newspaper was closed on July 4, 1960. Thirty one years later, independent journalism would return to Cuba in 1991 , but remain underground, occasionally tolerated, but often punished with prison time, and on occasion journalists would pay the ultimate price.

Omar Darío Pérez Hernández was an independent journalist who went missing in Cuba over 17 years ago and who had received threats from state security. His family following his disappearance in December 2003 was intimidated into silence. Omar can be seen briefly in a video conducting an interview with students expelled from university for signing the Varela Project in 2002.

Omar Darío Pérez Hernández missing Cuba journalist

This hostility to a free and independent press remains a hallmark of the Castro regime, and one that has been exported to Venezuela and Nicaragua.

President Miguel Díaz-Canel has been identified as a press freedom predator, and he is, but that does not mean that he calls the shots in Cuba. Raul Castro formally departed the scene in April 2021, although informally retaining control through General Luis Alberto Rodríguez-López Calleja, his former son-in-law, and others he and his family control such as Diaz-Canel.

Meanwhile the regime in Havana continues to use migration as a weapon against the United States to leverage policy concessions. Thirty years later and what was seen as one remaining problem of the Cold War has become a major problem in the region.

One hopes that policy makers will consider this the next time there are "fears" that the Castro regime will collapse.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), July 2, 2021 (Updated July 5, 2021)

RSF’s 2021 “Press freedom predators” gallery – old tyrants, two women and a European

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is publishing a gallery of grim portraits, those of 37 heads of state or government who crack down massively on press freedom. Some of these “predators of press freedom” have been operating for more than two decades while others have just joined the blacklist, which for the first time includes two women and a European predator.

Nearly half (17) of the predators are making their first appearance on the 2021 list, which RSF is publishing five years after the last one, from 2016. All are heads of state or government who trample on press freedom by creating a censorship apparatus, jailing journalists arbitrarily or inciting violence against them, when they don’t have blood on their hands because they have directly or indirectly pushed for journalists to be murdered.

Nineteen of these predators rule countries that are coloured red on the RSF’s press freedom map, meaning their situation is classified as “bad” for journalism, and 16 rule countries coloured black, meaning the situation is “very bad.” The average age of the predators is 66. More than a third (13) of these tyrants come from the Asia-Pacific region.

“There are now 37 leaders from around the world in RSF’s predators of press freedom gallery and no one could say this list is exhaustive,” RSF secretary-general Christophe Deloire said. “Each of these predators has their own style. Some impose a reign of terror by issuing irrational and paranoid orders. Others adopt a carefully constructed strategy based on draconian laws. A major challenge now is for these predators to pay the highest possible price for their oppressive behaviour. We must not let their methods become the new normal.”

New entrants

The most notable of the list’s new entrants is undoubtedly Saudi Arabia’s 35-year-old crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, who is the center of all power in his hands and heads a monarchy that tolerates no press freedom. His repressive methods include spying and threats that have sometimes led to abduction, torture and other unthinkable acts. Jamal Khashoggi’s horrific murder exposed a predatory method that is simply barbaric.

The new entrants also include predators of a very different nature such as Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, whose aggressive and crude rhetoric about the media has reached new heights since the start of the pandemic, and a European prime minister, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, the self-proclaimed champion of “illiberal democracy” who has steadily and effectively undermined media pluralism and independence since being returned to power in 2010.

Women predators

The first two women predators are both from Asia. One is Carrie Lam, who heads a government that was still democratic when she took over. The chief executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region since 2017, Lam has proved to be the puppet of Chinese President Xi Jinping, and now openly supports his predatory policies towards the media. They led to the closure of Hong Kong’s leading independent newspaper, Apple Daily, on 24 June and the jailing of its founder, Jimmy Lai, a 2020 RSF Press Freedom laureate.

The other woman predator is Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh’s prime minister since 2009 and the daughter of the country’s independence hero. Her predatory exploits include the adoption of a digital security law in 2018 that has led to more than 70 journalists and bloggers being prosecuted.

Historic predators

Some of the predators have been on this list since RSF began compiling it 20 years ago. Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad and Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, were on the very first list, as were two leaders from the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region, Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Belarus’s Alexander Lukashenko, whose recent predatory inventiveness has won him even more notoriety. In all, seven of the 37 leaders on the latest list have retained their places since the first list RSF published in 2001.

Three of the historic predators are from Africa, the region where they reign longest. Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, 79, has been Equatorial Guinea’s president since 1979, while Isaias Afwerki, whose country is ranked last in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index, has been Eritrea’s president since 1993. Paul Kagame, who was appointed Rwanda’s vice-president in 1994 before taking over as president in 2000, will be able to continue ruling until 2034.

For each of the predators, RSF has compiled a file identifying their “predatory method,” how they censor and persecute journalists, and their “favourite targets” – the kinds of journalists and media outlets they go after. The file also includes quotations from speeches or interviews in which they “justify” their predatory behaviour, and their country’s ranking in the World Press Freedom Index.

RSF published a list of Digital Press Freedom Predators in 2020 and plans to publish a list of non-state predators before the end of 2021.

https://rsf.org/en/news/rsfs-2021-press-freedom-predators-gallery-old-tyrants-two-women-and-european

President of Cuba since 10 October 2019

Predator since taking office

Cuba, 171st/180 countries in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index

PREDATORY METHOD: Soviet-style totalitarianism

The protégé of Raúl Castro, who he replaced as president in 2019 and then as first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba as well in 2021, Miguel Díaz-Canel is the first Cuban leader since 1959 not to be a member of the Castro family but, following the Castro family tradition, he maintains almost total control over news and information.

TV, radio and print media are all closely controlled by the government while the constitution bans privately-owned media outlets. Journalists who don’t toe the party line are subjected to arrests, arbitrary detention, threats of imprisonment, harassment, persecution, illegal home searches and confiscation and destruction of journalistic equipment.

FAVOURITE TARGETS: Independent media outlets, all dissident journalists

Intelligence officers keep a close watch on independent journalists, try to restrict their freedom of movement, subject them to brief arrests and delete information from their phones. Although Internet access is largely controlled by the state, bloggers and citizen-journalists may find a degree of freedom online, but they do so at their risk. Journalists are often jailed while others have been forced to leave the country. The government also monitors the coverage of foreign journalists closely, granting accreditation selectively and expelling those whose reporting is regarded as “overly negative.”

OFFICIAL DISCOURSE: Authoritarian communism

“Our journalism is honest, free and sovereign, like the land we defend #WeAreCuba #WeAreContinuity.” (A tweet by the president reacting indirectly to the release of RSF’s 2020 World Press Freedom – in which Cuba was ranked 171st out of 180 countries – on 25 April 2020).

President of Nicaragua since 2007 (after having served for the first time in 1979-1990)

Predator since his re-election for a third consecutive term, in November 2016

Nicaragua, 121th/180 countries in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index

PREDATORY METHOD: Economic suffocation and judicial censorship

Since late 2016, the independent press has been living a nightmare, under constant pressure by the Ortega government and its Sandinista National Liberation Front supporters. They are trying to silence critical voices using a number of tactics: threats, persecution, harassment and defamation campaigns, arbitrary arrests and detentions. A “law to regulate foreign agents” is designed to closely monitor media organisations and groups that receive financing from abroad. Ortega stops at nothing to control information. He has put in place a sordid system of economically choking independent media: Discriminatory policies in awarding government advertising, in granting radio and television frequencies, in limiting the importation of supplies and material. In addition, independent media are subjected to abusive audits, and private advertisers are pressured not to buy space in independent media. In September 2018, the government went so far as to explicitly prohibit the supplying of ink, paper and rubber, leading most of the country’s print newspapers to close. Finally, with an eye to the November 2021 presidential election, Ortega has stepped up information control, launching abusive prosecutions against all oppositionists, both in the political class and the media.

FAVOURITE TARGETS: The Chamorro family and private media

Publisher Carlos Chamorro, founder of the Confidencial news site, and his sister, Cristiana, founder of the Violeta Chamorro Foundation, which advocates for freedom of the press, are the president’s major targets. Chamorro, a fierce critic of Ortega, had to seek temporary exile in Costa Rica in 2019, because of threats and attacks fed by the government. Cristiana Chamorro, a journalist who became a presidential candidate in 2021, has been under house arrest since 3 June, on a government charge of money laundering. Nearly 20 journalists close to the foundation have been interrogated and intimidated by the prosecutor’s office, with the aim of legally overwhelming her, and blocking her election campaign.

OFFICIAL DISCOURSE: Paranoid and exaggerated

“Disinformation terrorism, directed from the United States and taken at face value by media from many countries, especially Costa Rica, is brutal, criminal and xenophobic.” (May 2020, in a speech directed at Costa Rican and American media – La Nación, Telenoticias, Noticias Repretel, CNN) – reviewing government statistics and rhetoric on management of the public health crisis).

“Journalists are the children of Goebbels.” (28th anniversary of the Nicaraguan Army, 1 September 2007).

https://rsf.org/en/predator/daniel-ortega

President of Venezuela since 2013

Predator since taking office

Venezuela, 148th/180 countries in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index

PREDATORY METHOD: Censorship and deliberately orchestrated economic strangulation

The Maduro administration’s authoritarian and abusive treatment of independent media has not let up since 2017. Journalists are subjected to arbitrary arrest and violence by the police and intelligence services. The National Telecommunications Commission (CONATEL) strips overly critical radio and TV stations of their broadcast frequencies, and coordinates Internet cuts, social media blocking and confiscation of equipment. Most opposition print media have not survived all the various forms of harassment, while online media are subjected to repeated cyber-attacks that make their reporting more and more complex and expensive. Foreign reporters are often arrested, questioned and deported. Many of Venezuelan journalists have been forced to flee the country since 2018 because of the threats and physical dangers.

FAVOURITE TARGETS: Privately-owed media, the newspaper El Nacional

More than 100 media outlets have closed since Maduro became president while El Nacional, the prestigious national daily founded in 1943, had to stop producing a print version in December 2018. It is still active online but continues to be one of the government’s favourite targets. Its headquarters was seized on 14 May 2021 and it was ordered to pay 13 million US dollars (about 11 million euros) to Diosdado Cabello, a parliamentarian who is Vice-President of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, the ruling party founded by the late President Hugo Chávez. Cabello’s libel suit could result in El Nacional being permanently stripped of its headquarters and all of its assets in Venezuela. In 2021, the government accused several NGOs and independent media, including the Efecto Cocuyo, Caraota Digital and El Pitazo news sites and Radio Fe y Alegría, of being “journalism mercenaries” and of receiving foreign funding to bring down the government.

OFFICIAL DISCOURSE: Paranoid denigration

“Much of the media war to which Venezuela is being subjected is designed to ensure that no one comes near Venezuela, that no one comes to invest, although Venezuela is the best country in the world to invest in.” (Speech on 11 February 2019 launching “Marca País” (Country Brand), an initiative intended to promote tourism and exports and show the “real country.”)

“I denounce the international campaign waged by CNN in Spanish, this laboratory of lies, psychological warfare and garbage against the country, against Venezuela. A campaign that is also organised by NTN24, a trashy television channel funded by the paramilitary Alvaro Uribe, and by the Miami Herald, the media that is the depository of all the lies against Venezuela (...) [Media) that are full of hate, rage and madness. [Media] that try to poison and to pour their poison on Venezuela and the world.” (Speech at the inauguration of 80 homes at Caricuao, Caracas, on 18 September 2014).

https://rsf.org/en/predator/nicolas-maduro

From the Archive

Foreign Policy, May 14, 2019

Venezuelan Democracy Was Strangled by Cuba

Decades of infiltration helped ruin a once-prosperous nation.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez (L) speaks with Cuban President Fidel Castro (R) on 16 April, 1999, Egilda Gomez/AFP/Getty Images)

May 14, 2019, 1:34 PM

The U.S. role in Venezuela has come under plenty of scrutiny in recent weeks. But far more important than the largely ineffective efforts by Washington at backing a besieged opposition has been the influence of Havana over the regimes of both former President Hugo Chávez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro. On April 30, U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to impose a full embargo and high-level sanctions on Cuba over the alleged Cuban troop presence in Venezuela. “Hopefully, all Cuban soldiers will promptly and peacefully return to their island!” he tweeted. The Cuban government denies these accusations.

Yet the United States is not the only one making these claims. The secretary-general of the Organization of American States, Luis Almagro, declared last December that the Cuban government has been involved in military and intelligence activities in Venezuela by training forces and commanding operations. And accounts from former Venezuelan military officials—reported by the Washington Post—also suggest that Cubans are playing a critical role in the Venezuelan armed forces.

This February, Rocío San Miguel, the president of Control Ciudadano, a Venezuelan nongovernmental organization linked to the opposition dedicated to military affairs, told the BBC that the Cubans have interfered in five key areas of the Venezuelan government: registers and notaries, identification and immigration, the Bolivarian National Police, intelligence and counterintelligence bodies, and the national armed forces. What might have seemed like a conspiracy theory a decade ago now raises few doubts.

“If oil is wealth, oil was [Fidel] Castro’s obsession.” That was the late Venezuelan journalist, diplomat, and historian Simón Alberto Consalvi’s response when asked about the former Cuban leader’s targeting of Venezuela’s wealth. The quote opens Días de Sumisión (Days of Submission), a 2018 book by the Venezuelan journalist and writer Orlando Avendaño that analyzes the history of Cuba’s interference in Venezuela’s democratic system, and how Castro opened the way for Chávez to take the presidency of the country.

Avendaño argues that the beginning of Venezuela’s gradual process of submission to Cuba didn’t start with the rise of Hugo Chávez to power. Instead, he writes, it was a very complex and sweeping long-term project orchestrated by Castro and supported by the country’s hard left that progressively corroded the Venezuelan institutions.

The initial hopes were more cooperative. Twenty-two days after the triumph of the Cuban revolution, Castro traveled to Venezuela on Jan. 23, 1959, in his first official foreign visit. Castro saw in Rómulo Betancourt, Venezuela’s first elected president after the fall of the dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez, a political and economic ally who could fund his project with massive oil subsidies. Betancourt had supported Castro with arms, money, and, most importantly, political backing during the guerrilla war in Cuba. After all, they had certain things in common. Both had emerged from the intellectual left. And both wanted a drastic change in a Latin America ruled by military dictatorships for decades.

“I have felt a greater emotion upon entering Caracas than the one I experienced upon entering Havana … To these good and generous people, to whom I have given nothing and from whom we Cubans have received everything, I promise to do for other peoples what you have done for us. I promise not to consider ourselves entitled to rest in peace while there is still one Latin American man living under the opprobrium of tyranny,” Castro told 100,000 people gathered on Bolivar Avenue in Caracas.

But after 1959, Betancourt’s attitude toward Castro shifted, especially as Cuba moved closer to the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, Betancourt had been a member of the Communist Party of Costa Rica while in exile, but his views evolved toward a more democratic stance over the years. Betancourt was still against U.S. imperialism but also against Soviet imperialism. And although he had defended a revolution from the left in the past, he always thought that it also meant fair elections, something Castro wasn’t willing to accept.

The meeting between the two leaders failed, and Castro left Caracas without oil for his political project and with one more political enemy. In his 2008 book Power and Delirium, the Mexican writer and historian Enrique Krauze describes the meeting as “brief and harsh.” When Castro asked for oil, Betancourt told him Venezuela sold oil, not gifted it, and that Cuba would be no exception. The summary executions in Cuba further alienated Betancourt from his former ally. Two years later, in November 1961, Cuba and Venezuela broke off relations.

From that point on, Castro began what Avendaño, in Days of Submission, describes as the three stages of a complex process of “persistent and obsessive attempts” to control Venezuela at all cost: “The Uprising,” “The Infiltration,” and “The Consolidation.” Each used different strategies, and each came in response to the failure of the previous stage

First came the insurrection: the process of armed conflict in Venezuela, guerrilla warfare sponsored directly by Havana in the 1960s—a tactic used elsewhere in Latin America and on other continents, where Cuban advisors became a mainstay of communist insurrections.

According to Avendaño’s interviews with participants, Castro created a relationship with the main guerrilla group in the nation, called the José Leonardo Chirino Front after an 18th-century rebel. The front was led by Douglas Bravo, a former guerrilla and leader of the Party of the Venezuelan Revolution. This group was just one part of the National Liberation Front, a paramilitary union that brought together all the guerrillas in Venezuela and looked to Havana for its political compass. It failed, was devastated militarily, and eventually submitted a rather opaque pacification process. That pushed Castro toward a different strategy: infiltration.

The new tactic was to introduce individuals sympathetic to the Cuban revolution into the Venezuelan armed forces so that they could develop there to expand the project, attract officers, and, in a few years, achieve the capacity for fundamental strength and support to take power. This stage culminated in the attempted coup of Feb. 4, 1992. At that time, a group of military officers commanded by, among others, Chávez took up arms against the then constitutionally appointed president, Carlos Andrés Pérez—but the rebel troops surrendered in Caracas within the first 24 hours. “We have not met our objectives … for now,” said Chávez in a televised message, surrounded by military officers as he asked his forces to lay down their arms.

The coup may have ended up being a military failure, but it became a political victory for the radical opposition groups. At the end of the 1980s, after political deterioration and economic crisis, Venezuelans were disenchanted with democracy. Pérez took office on Feb. 2, 1989, with promises of economic reform, but instead inflation struck, prices rose, and shortages began to appear all over the country. On Feb. 27, 1989, citizens took to the streets of Caracas in protest against the government but were violently repressed by the police in clashes that ended in hundreds of deaths. In this context, a large part of society came to support the idea of a coup, the army was seen as the salvation of the nation, and, after 1992, Chávez was seen as a hero.

Cuba seized this opportunity, moving into a strategy of consolidating its relationship with the Venezuelan left. At the beginning of 1994, then-Venezuelan President Rafael Caldera received Jorge Mas Canosa, an anti-Castro leader, in Miraflores palace. In response to this, Castro decided to invite Chávez (who remained a popular member of the opposition at the time) to give a lecture at the University of Havana, after his release from prison. Castro received him personally at the airport, where Chávez greeted him with rapt admiration. Almost five years after that reunion, Chávez was elected president of Venezuela.

After Chávez was elected in 1998, the relations between the two nations quickly began to narrow. The triumph of Chávez during the political and military crisis of 2002 and 2003 let Havana penetrate and gain ideological control of the national armed forces and Venezuelan oil companies. It began with economic agreements and social exchanges, mostly oil in exchange for Cuban doctors, professors, and sports coaches. That took place openly but then shifted to military personnel and intelligence forces. For Chávez, this presence in his country of Cuban intelligence forces—some of the best-trained in the continent—could help him maintain his power and political stability in case of internal or external threats. For Castro, this would eventually expand his control over Venezuelan institutions and even over Chávez’s personal life and top secrets. Over the years, the Venezuelan military leadership allowed all this interference to take place in exchange for money, privileges, and immense access to power.

During the following years, especially after Chávez’s death in 2013, Havana would continue to exert its influence over the South American nation. Cuba has become critical to keeping Maduro’s regime in place in an “oil for repression” scheme in which Havana helped the socialist leader in his power struggle with the opposition in exchange for fuel, contributing to the country’s political, social, and economic crisis today. Last year, Reuters reported that Venezuela had bought nearly $440 million worth of foreign oil and shipped it to Cuba to fulfill its commitments to Havana. The Caribbean country, along with Russia, is one of the few backers holding off the abrupt collapse of the current Venezuelan regime. The destiny of Venezuela’s democracy could lie in Cuba’s hands. A far economically and militarily stronger country has ended up ideologically conquered—and politically devastated—by a far smaller and poorer one.

Jorge Carrasco is a Cuban-born journalist based in Brazil.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/05/14/venezuelan-democracy-was-strangled-by-cuba/

Reporters Without Borders, August 25, 2020

Two journalists murdered just days apart in Venezuela

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) calls on the Venezuelan authorities to conduct impartial investigations into the murders of two journalists in the past week in order to quickly identify the perpetrators and instigators.

Reporter and cameraman Andrés Eloy Nieves Zacarías was shot dead when at least 10 heavily-armed members of Venezuela’s Special Action Forces (FAES) burst into the recording studio of La Guacamaya TV, a local TV station located in the home of the station’s director, Frankie Torres, in Cabimas, in the northwestern state of Zulia, on 21 August. They also shot dead Torres’ son, Víctor Torres.

A few hours after the raid, the FAES said the two victims were members of a “criminal gang” – a claim immediately denied by the families of the victims.

This double murder came just three days after the body of José Carmelo Bislick, a teacher and presenter on local Radio Omega 94.1 FM, was found at a roadside in Güiria, a town in the northeastern state of Sucre, on 18 August. Bislick had recently drawn attention to cases of corruption in Güiria involving extortion and trafficking (in fuel, drugs and people).

“We are appalled by these acts of unspeakable violence, whose victims included two journalists exercising their right to inform, and we ask the Venezuelan police and judicial authorities to conduct impartial investigations to identify the perpetrators and instigators,” said Emmanuel Colombié, the head of RSF’s Latin America bureau.

“We also point out that state censorship, arbitrary arrests and violence against journalists – of which the perpetrators include the police and intelligence services – continue to take place throughout the country and to pose a serious threat to the freedom of expression.”

La Guacamaya TV supports President Nicolás Maduro’s government, while Bislick was an active member of Maduro’s ruling Unified Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). The fact that both victims supported government policy is unusual. In most cases, it is independent journalists or journalists critical of the government who are the targets of attacks.

According to Espacio Público, a Venezuelan NGO, there have been at least 270 attacks against journalists and 686 violations of the right to free speech in Venezuela since the start of the year. The Covid-19 crisis, compounded by frequent orchestrated restrictions on Internet access, has made it extremely difficult for independent journalists to cover the news.

Venezuela is ranked 147th out of 180 countries in RSF's 2020 World Press Freedom Index.

https://rsf.org/en/news/two-journalists-murdered-just-days-apart-venezuela

Pew Research Center, March 19, 2021

Venezuelans, Burmese among more than 600,000 immigrants eligible for Temporary Protected Status in U.S.

By D’Vera Cohn

Activists march toward the White House on Feb. 23 in a call for Congress and the Biden administration to pass legislation granting immigrants with Temporary Protected Status a path to citizenship. (Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images)

The Biden administration has added Venezuelans and Burmese to the list of people eligible for Temporary Protected Status, a program that gives immigrants from select countries time-limited permission to live and work in the United States.

The Department of Homeland Security on March 8 designated immigrants from Venezuela as eligible for TPS for 18 months. Since January, Venezuelans also have been eligible for deportation relief and work authorization under a program called Deferred Enforced Departure (see text box).

In designating Venezuelans as eligible for TPS, the Biden administration stated that the nation “is currently facing a severe humanitarian emergency” with impacts on its economy, human rights, medical care, crime, and access to food and basic services. The notice also cited charges of election fraud on behalf of President Nicolás Maduro, who has led the country since 2013. The TPS designation expires in September 2022.

The designation of Burma (Myanmar) will apply for 18 months to immigrants who have lived in the U.S. since March 11. According to news accounts, about 1,600 people are estimated to be eligible. In announcing the TPS designation, U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas cited the impact of the Feb. 1 military coup, including “continuing violence, pervasive arbitrary detentions, the use of lethal violence against peaceful protesters, and intimidation of the people of Burma.”

Overall, it is estimated that more than 600,000 immigrants from 12 countries – potentially including more than 300,000 Venezuelans – currently have or are eligible to have a reprieve from deportation under TPS, which covers those who fled designated nations because of war, hurricanes, earthquakes or other extraordinary conditions that could make it dangerous for them to live there. (The estimated total is based on those currently registered and those estimated to be eligible from Burma and Venezuela.) TPS recipients who meet certain conditions could be granted a pathway to citizenship under legislation proposed by President Joe Biden and congressional Democrats before Venezuela and Burma were added to the list of TPS-eligible nations.

Federal immigration officials may grant TPS status to immigrants for up to 18 months initially based on conditions in their home countries and may repeatedly extend eligibility if dangerous conditions persist.

The Trump administration had sought to end TPS for nearly all beneficiaries, but was blocked from doing so by a series of lawsuits.

Under extensions granted by the Department of Homeland Security in recent years, the earliest that TPS status could expire would be in September for immigrants from Somalia and Yemen. TPS benefits are set to expire in October for those from El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua and Sudan. For TPS beneficiaries from South Sudan and Syria, benefits would expire in 2022. The deadlines for most groups were extended by the Trump administration; the deadline for Syrians was extended by the Biden administration.

After taking office Jan. 20, Biden asked Congress to pass legislation that would allow TPS recipients who meet certain conditions to apply immediately for green cards that let them become lawful permanent residents. TPS currently does not make people automatically eligible for permanent residence or U.S. citizenship.

The legislation proposed by Biden and congressional Democrats would allow TPS holders to apply for citizenship three years after receiving a green card, which is two years earlier than usual for green-card holders. Citizenship would be granted if they pass additional background checks and meet the usual naturalization conditions of knowledge of English and U.S. civics.

The TPS provisions are part of broader proposed legislation that would grant similar benefits to some unauthorized immigrant farmworkers and recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Other U.S. unauthorized immigrants, after applying for temporary legal status, would be required to wait five years to apply for a green card that would make them eligible for citizenship later.

Most current TPS beneficiaries have lived in the U.S. for two decades or more. Those from Honduras and Nicaragua were designated eligible based on damage from Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and must have been living in the country since Dec. 30 of that year. The current protection for immigrants from El Salvador applies to those who have lived in the U.S. since Feb. 13, 2001, following a series of earthquakes that killed more than a thousand people and inflicted widespread damage. The TPS designation for Haiti was based on a damaging earthquake in January 2010; immigrants are eligible if they entered the U.S. by early 2011.

Immigrants with TPS live in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, according to the Congressional Research Service. The largest populations live in California, Florida, Texas and New York, which traditionally have had had large immigrant populations.

Once the Department of Homeland Security designates a nation’s immigrants as eligible for Temporary Protected Status, immigrants may apply if they entered the U.S. without authorization or entered on a temporary visa that has expired. Those with a valid temporary visa or another non-immigrant status, such as foreign students, are also eligible to apply.

To be granted TPS, applicants must meet filing deadlines, pay a fee and prove they have lived in the U.S. continuously since the events that triggered relief from deportation. They also must meet criminal record requirements – for example, that they have not been convicted of any felony or two or more misdemeanors while in the U.S., or been engaged in persecuting others or terrorism.

Federal officials are required to announce 60 days before any TPS designation expires whether it will be extended. Without a decision, it automatically extends six months.

Congress and President George H.W. Bush authorized the TPS program in the 1990 immigration law, granting the White House executive power to designate and extend the status to immigrants in the U.S. based on certain criteria.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published March 1, 2021.

D’Vera Cohn is a senior writer/editor focusing on immigration and demographics at Pew Research Center.