The Washington Post's Olivier Knox offers a flawed analysis on Cuba in The Daily 202. Knox cites a "Reuters piece about American farmers blaming Cold War-driven economic sanctions on Cuba for stymieing food sales to the island, which therefore buys pricier imports from places like Europe. Cuba suffers from food shortages and things are getting worse because of the war in Ukraine, a major global wheat supplier."

No mention that Cuba received 25 tons of wheat from Russia in an “emergency shipment” in mid-February 2023. Nor if the wheat had been stolen from occupied Ukraine territory. The Castro regime has been backing Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine.

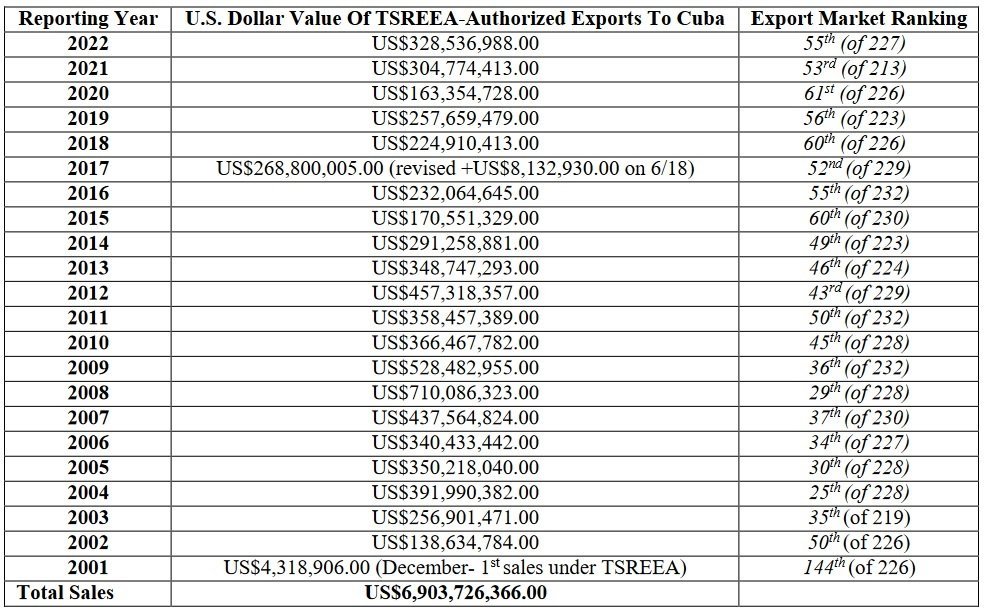

This also ignores what has taken place over the past 23 years. In 2000 the Clinton Administration opened cash and carry trade with Cuba, but without credits being available with the passage of Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (TSRA), 22 U.S.C. §§ 7201-7211 .

Over $6.9 billion ended up in the coffers of American companies doing business with the Cuban dictatorship, but what is left out is what it cost long time trading partners with the Castro regime. James Prevor, President and Editor in Chief of the publication Produce Business in the October 2002 article, “Cuba Caution”, described how Havana "had exhausted all its credit lines and, at best, was simply rotating the accounts. When the opportunity came to buy from the United States, Cuba simply abandoned all those suppliers who supported the country for 40 years and began buying from us."

Source: CubaTrade.org

However the low point in trade between Cuba and the United States during this period coincided with the Obama Administration repeatedly loosening U.S. sanctions and normalizing diplomatic relations.

The last year of the George W. Bush Administration, which had what apologists call a "hard line" policy with the Cuban government, saw over $710 million dollars in exports sold to Havana, Cuba. Meanwhile, Obama's repeated loosening of sanctions that began in 2009, continued in 2012 and dramatically expanded during 2014-2016 saw annual U.S. exports bottom out in 2015 to $170.5 million dollars before rising to 232 million in the last full year of his presidency.

This record does not find a positive correlation between loosening sanctions and increased agricultural sales.

Knox quotes the same Reuters article, “The United States created a loophole to its trade embargo with Cuba in 2000 to allow for food sales, but it still denies Cuba credit, forcing the communist-run government to pay cash up front for products it purchases from U.S. growers,” and concludes by asking: "But what has the policy accomplished? What will it accomplish? What happens if a food crisis destabilizes Cuba?"

Professor Jaime Suchlicki, Cuban Studies Institute

Cuba scholar Jaime Suchlicki at the Cuban Studies Institute on April 10, 2023 published an important analysis titled “The Folly of Investing in Cuba” that outlines a number of pitfalls both economic and moral to doing business with the Castro dictatorship that is a must read.

Existing U.S. sanctions have protected American taxpayers from having to shell out billions of dollars to subsidize the Castro dictatorship.

Others have not had the benefit of this policy.

China canceled $6 billion dollars in Cuban debt in 2011,

On November 1, 2013 the government of Mexico announced that it was ready to waive 70 percent of a debt worth nearly $500 million that Cuba owes it. The former president of Mexico Vicente Fox protested the move stating: “Let the Cubans get to work and generate their own money…They’re normally like chupacabras. The only thing they’re looking for is someone to give them money for free.”

In December 2015 it was announced that Spain would forgive $1.7 billion that the Castro regime owes it. In December of 2013, Russia and Cuba quietly signed an agreement to write off $32 billion of Cuba's debt to the former superpower. Western governments pursued Cuban maritime debts seizing Cuban vessels and negotiating payment through Canadian courts.

The 2015 debt restructuring accord between Cuba and the Paris Club, according to Reuters, "forgave $8.5 billion of $11.1 billion, representing debt Cuba defaulted on in 1986, plus charges."

The 19-member Paris Club comprises Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Britain, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland is owed money by Cuba Companies, with the exception of U.S. companies, doing business with Cuba when they are not paid pass the costs off to their respective governments, who in turn pass the costs off to taxpayers.

This is something to consider when the Agricultural lobby and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce argue that U.S. laws should be changed and the United States should join the long line of governments seeking to collect from the Castro regime, a deadbeat dictatorship.

Lastly, and most importantly is the question of food security in Cuba, and the prospect of a food crisis. There is a food crisis in Cuba, and it has been going on for some time.

The Obama 2014-2017 opening did not improve food security, but worsened it due to increased tourism from the United States. The New York Times reported on December 8, 2016 in the article "Cuba’s Surge in Tourism Keeps Food Off Residents’ Plates" that more U.S. tourists have translated into less food for everyday Cubans thanks to continued central planning by the communist regime. “The government has consistently failed to invest properly in the agriculture sector,” said Juan Alejandro Triana, an economist at the University of Havana. “We don’t just have to feed 11 million people anymore. We have to feed more than 14 million.”

Over six decades to the present day, between 70% and 80% of Cuba's food has and continues to be imported. This included the years when Cuba was heavily subsidized by the Soviet Union, and was part of the East Bloc. Since 2000, much of the food purchased by Havana has been imported from the United States. Despite this, rationing continued during the peak years (2011 - 2014) when the Cuban government received massive amounts of assistance from Venezuela's Chavez regime. What about Cuba's domestic agricultural production? Diario de Cuba in their February 7, 2022 article, "Cubans go hungry and Acopio leaves 22 tons of tomatoes to rot, farmers denounce," cites Cuban agronomist Fernando Funes-Monzote who stated that "Cuban agriculture does not need to produce more food," because "50% of what is grown today is lost before reaching the consumer."

This is part of the "internal blockade" that thousands of Cubans have referred to, and signed a petition calling for its end.

Prior to the 1959 communist revolution in Cuba, Cuban farmers were able to produce enough food to feed the entire Cuban populace. The Cuban Studies Institute found that between 1952-1958 there was "a successful nationalistic trend aimed to reach agricultural self-sufficiency to supply the people’s market demand for food." Despite the efforts to violently overthrow the Batista regime in the 1950s, "the Cuban food supply grew steadily to provide a highly productive system that, in daily calories consumption, ranked Cuba third in Latin America."

This ended when the Castro dictatorship seized and collectivized properties, and prohibited farmers selling their crops to non-state entities, in the early years of the revolution. Farmers no longer decided how much to produce, or what price to sell. The communist regime established production quotas and farmers were (and are) obligated to sell to the state collection agency, called Acopio.

Havana calls the United States economic embargo a "blockade." This is not true as the State Department (and U.S. - Cuba trade statistics over the past 20 years) demonstrate. A meme appeared on social media in Spanish that outlines the reality of the Castro regime's internal blockade, and Cuban scholar and journalist Carlos Alberto Montaner on July 15, 2021 gave a commentary on this. Below is a translation to English of this meme.

"The blockade does not prohibit fishermen in Cuba from fishing, the dictatorship does;

The blockade does not confiscate what farmers harvest, the dictatorship does;

The blockade does not prohibit Cubans on the island from doing business freely, the dictatorship does;

The blockade did not destroy every sugar mill, textile factory, shoe store, canning factory, the dictatorship did;

The blockade is not responsible for Cubans being paid with worthless pesos and stores sell you products with American dollars; the dictatorship is;

The blockade is not responsible that Cubans are beaten and imprisoned for thinking differently, the dictatorship is;

The blockade is not responsible that there are hundreds of Cuban political prisoners who have not committed any crime, the dictatorship is;

The blockade is not responsible for sending Cubans US dollars that they give to you in worthless pesos in the Western Union, the dictatorship is;

The blockade is not responsible for the dictatorship building hotels and the roofs that fall on Cubans' heads, the dictatorship is;

The blockade is not responsible for hospitals in Cuba that are disgusting, the dictatorship is;

The blockade is not responsible for not having water in homes, for not maintaining the aqueduct system, the dictatorship is;"

The United States does not have a "blockade" on Cuba, but porous economic sanctions with a focus on cutting off funds to the military that controls most of the Cuban economy. What the meme does reveal is the full extent of the "internal blockade" on Cubans imposed by the Castro dictatorship. Remittances continue to flood Cuba from the exile community in South Florida.

Professor Amalia Dache, University of Pennsylvania

Afro-Cuban American scholar, Amalia Dache, an associate professor in the Higher Education Division at the University of Pennsylvania who "engages in research within contested urban geographies, including Havana, Cuba; Cape Town, South Africa; and Ferguson, Missouri" explained in July 21, 2021 the reality of the US embargo and the Castro regime's internal blockade.

"No. It’s very hard for me to say that as someone who still has family living in Cuba. But lifting the embargo would not magically improve their lives. Here’s why: To understand the US embargo, it’s important to know about the internal blockade the Cuban government imposes on its own people. For example, the US embargo does still allow for food and medicine sales to Cuba. The Cuban government buys $100 million worth of chicken from producers in the United States annually. It sells that chicken to the Cuban people at a marked-up rate, sometimes at double the cost, and uses the profit to fund the regime. Other countries trade freely with Cuba, but because the government is heavily involved, the internal blockade keeps those profits from reaching the Cuban people. Poor neighborhoods — Afro Cuban neighborhoods — get the worst of the shortages. The police and military get money for new cars and surveillance technology."

The Cuban dictatorship is expert in promoting a false narrative about their regime repeating their false claims about the blockade, and their achievements in healthcare and education. 14ymedio revealed that “the two sectors on which the Cuban regime has founded its popularity since 1959, health and education, combined received in 2022 one tenth the budget dedicated to business services and real estate and rentals. The area, considered a mixed bag that includes tourism, received 33% of the budget last year (23.360 billion pesos, almost one billion dollars at the official exchange rate), compared with the other two, which taken together barely received 3.3%”. This is reflected in the disastrous state of both sectors.

The Washington Post, April 14, 2023

Food sales to Cuba, long day-care wait lists. Your weekly non political political stories.

Analysis by Olivier Knox

with research by Caroline Anders

April 14, 2023 at 12:04 p.m. EDT

Welcome to The Daily 202! Tell your friends to sign up here. Today I learned the 17th arrondissement of Paris has a website where residents can report having seen a rat. https://signalerunrat.paris

The big idea

Food sales to Cuba, long day-care wait lists. Your weekly non political political stories.

Farmers complain sanctions hamper food sales to Cuba. The pain of long wait lists for day care. Why trucks (and “trucks”) rule the road. And how Bali copes (or doesn’t) with badly behaved tourists. These are your weekly non political but political stories.

The Daily 202 generally focuses on national politics and foreign policy. But as passionate believers in local news, and in redefining “politics” as something that hits closer to home than Beltway “Senator X Hates Senator Y” stories, we try to bring you a weekly mix of pieces with significant local, national or international importance.

Please keep sending your links to news coverage of political stories that are getting overlooked. They don’t have to be from this week! The submission link is right under this column. Make sure to say whether I can use your first name, last initial and location. Anonymous is okay, too, as long as you give a location.

Cuba goes hungry

From Robert M. in Blackwater, Ariz., comes this Reuters piece about American farmers blaming Cold War-driven economic sanctions on Cuba for stymieing food sales to the island, which therefore buys pricier imports from places like Europe. Cuba suffers from food shortages and things are getting worse because of the war in Ukraine, a major global wheat supplier.

“A delegation of U.S. farm sector representatives in Havana said that embargo restrictions, despite some exceptions for agricultural products, still complicate efforts to ship food that might otherwise prove a lifeline for Cubans,” Dave Sherwood reported.

“The United States created a loophole to its trade embargo with Cuba in 2000 to allow for food sales, but it still denies Cuba credit, forcing the communist-run government to pay cash up front for products it purchases from U.S. growers.”

The politics: Support for the decades-old embargo in places like Florida and New Jersey makes it hard to weaken. But what has the policy accomplished? What will it accomplish? What happens if a food crisis destabilizes Cuba?

14ymedio, April 14, 2023

Cuba’s 2022 Accounts Confirm That the Country Spends 16 Times More on Building Hotels than on Healthcare

Five star hotel under construction, on First and B streets, Havana (14ymedio)

Posted on April 14, 2023

Categories 14ymedio, Translator: Silvia Suárez

14ymedio, Havana, 13 April 2023 — The two sectors on which the Cuban regime has founded its popularity since 1959, health and education, combined received in 2022 one tenth the budget dedicated to business services and real estate and rentals. The area, considered a mixed bag that includes tourism, received 33% of the budget last year (23.360 billion pesos, almost one billion dollars at the official exchange rate), compared with the other two, which taken together barely received 3.3%.

The accounts are even worse if these two areas are separated. The health and public services received 2.1% of the budget (1.520 billion pesos or 63.4 million dollars), education received 1.2% (820 million pesos or 34 million dollars), that is 16 and 27 times, respectively, less than the so-called “business and real estate services.”

The poor investment in health contrasts with the gigantic income the Cuban state obtains from exporting medical services, the country’s main source of hard currency. According to official data, collected from annual statistics published by the National Statistics and Information Office (Onei), in 2021, they collected 4.349 billion dollars from the export of health services, although between 2011 and 2015 they were able to obtain more than 11.500 billion, according to the information provided by the former Minister of Economy José Luis Rodríguez.

That imbalance in the budget for that sector, which is diverse and non-specific but associated with hotel construction, has been going on for many years; in 2021 the pinch was even greater, it received 35% of the total budget, though the total amount was smaller.

The only area that dares to approach it, although still far behind, is the manufacturing industry, which receives 17.3% of the budget, totaling 12.304 billion pesos. The sugar industry is excluded from that, with its own budget line which allows us to see the ruinous budget assigned to that notable product of Cuban industry — barely 0.6%, with 410 million pesos.

With a percentage in the double digits, the transportation, food and communications sector received 10.3% (7.316 billion pesos).

In fourth place, though barely noticeable to Cubans, was the provision of water, electricity and gas, which received 6.988 billion or 9.8.% of the total budget. Although the figure seems padded when compared to some of those already mentioned, it continues to be less than one third of what was budgeted for real estate.

Two other sectors that fared well were mining and quarries, an area in which the government has placed a lot of hope for the supposed benefits of exporting nickel, among other minerals. Those rceived 5.066 billion pesos. Hotels and restaurants — the portion of tourism not related to real estate — received 3.226 billion pesos, and commerce and repair of personal effects received 2.506 million pesos, ahead of what should be a priviledged sector, agricultural production.

To this area, specifically designated by the government as a “priority”, a mere 1.855 billion pesos were budgeted, only 2.6% of the total budget. “Amid a situation of food insecurity, it is worrisome that the relative weight of investment in agriculture remains stagnant at a leven which is 12 times lower than the relative weight of investment in business services and real estate,” stated Cuban economist Pedro Monreal on his Twitter account Wednesday.

The expert reminds us that the agriculture sector employs more than 17% of Cubans, the sector with the most employment, but the low level of investment makes it a beacon of low productivity that weighs down economic growth for the entire country.

“It is probably understood, but worth repeating — without a major investment in agriculture it will not be possible to overcome food insecurity in Cuba, nor to mitigate inflation, nor poverty, nor will there be national development. The slogans they come up with matter very little,” he said.

The data provided by the National Statistics and Information Office (Onei), which are for last year, lay bare not only the (now) old evidence that tourist construction is disproportionate compared to other sectors at a time when it is not on par with profits. It also reflects the constant contradiction of the government discourse that stops investing in pillars of social justice such as food (fishing uses 0.7% of total investment) health or education, to capture foreign currency which, to make matters worse, does not arrive.

The small amount budgeted for the agriculture sector, moreover, serves to bring down tourism. As the reproaches come from the ranks of officialdom itself, tourists spend more on food when they come to Cuba than on paying for hotel accommodations, but if there is no food, the country loses out on that income as well and informed travelers lose the incentive to come.

Translated by: Silvia Suárez

Cuban Studies Institute, April 10, 2023

The Folly of Investing in Cuba

By Jaime Suchlicki

A recent proposal to modify the U.S.-Cuba embargo and allow investments and travel to Cuba, introduced by a small bi-partisan group of members of the U.S. Congress, is likely to fail. Yet it shows the lingering perception that internal change in Cuba can be fostered by U.S. policies and that the 60 years of intransigent Cuba policy can be modified with travel and investments.

For some investors, Cuba has the appearance of offering significant opportunities. It is the largest island in the Caribbean, with a population of over 11 million; it is close to the United States, which should provide a large and prosperous market; it has a well-educated and trained population; and it suffers from a great need for material goods and for the rebuilding of its deteriorating infrastructure. Also, as the Castro era draws to an end and U.S.-Cuba relations eventually are normalized, tourism, mining, agriculture, and construction will become significant targets for foreign investment.

And yet, in reality Cuba combines the worst features of underdeveloped and communist societies. It is probably the most inefficient among the former socialist nations. By far, it is also the poorest in terms of per capita income. It follows, therefore, that all the drawbacks and disadvantages to investing in less developed and socialist countries apply with special emphasis to the Cuban case. Cuba combines the worst of both worlds as far as investment opportunities are concerned.

Moreover, Cuba’s economic decline in the last five years has reached catastrophic proportions, with no end in sight for the deflationary spiral. The entropy of the Cuban economy as it keeps on contracting has no parallel in recent history, perhaps with the exception of the Cambodian experience under the Khmer Rouge.

Cuba’s extreme dependence on foreign trade and the adoption of its economy for nearly three decades to an unnatural and immense Soviet subsidy inflow, which created an artificial economy that has now disappeared, paradoxically has proved to be its own nemesis. Cuba does not have a viable economy of its own. As nearly every category of inputs keeps on decreasing, so the spiraling vicious circle of pauperization keeps on descending unremittingly.

In Cuba there is no internal market to speak of. Consumption is limited by a strict and severe rationing regime. Whatever transactions take place outside it are in the illegal black market, which operates with scarce dollars and stolen merchandise. Meanwhile, the Cuban peso continues to depreciate as its purchasing power becomes nil and its function as a means of exchange approximates the vanishing point. This process is being accelerated by a huge and persistent governmental budgetary deficit and the virtual absence of any stabilizing fiscal and monetary policies. Under such extreme conditions and with no foreign exchange reserves, convertibility is totally out of the question.

Sugar production, Cuba’s mainstay export, has reached levels comparable to that of the Great Depression period, while the prices of other supplementary primary commodities continue their downward trend in the international market.

Efforts at diversifying production both for domestic and export purposes have proved to be notorious failures, despite enormous amounts of misplaced investment. Furthermore, the economic and social infrastructures of the nation are not only in a state of disrepair but are actually collapsing. The outdated electric grid cannot supply the meager needs of consumers and industry, transportation services have almost vanished, communication facilities are totally obsolete, and sanitary and medical services have deteriorated so badly that contagious diseases of epidemic proportions constitute a real menace to the population.

Under these present conditions it would be risky, if not foolhardy, to invest in Cuba. Even the export sectors, like tourism, which seem to be relatively prosperous and immune to the economy’s malady, will eventually fall victim to the general poverty of the country. It is impossible for isolated sectors of enclaves of economic activity to survive indefinitely under such cataclysmic conditions.

One other point of extreme importance to consider when evaluating the economic wisdom of investing in Cuba under Castro is that of the general subsidization of economic activities. The extremely lax fiscal, tariff, and labor policies now in force are likely to be rapidly replaced by more economically rational ones as soon as the current regime is supplanted. The present policies can only be understood as the desperate actions of a political system in urgent need of short-term financial resources in order to retain its grip of power.

Related to the preceding point is the crucial issue of the structural changes that will eventually take place in the price system as Cuba inevitably undergoes its transformation from a centrally planned and administered economy into a market-based one. At that time, a revolutionary mutation will take place in the cost accounting and price practices and calculation of business enterprises. There is no way now for an investor to anticipate the impact of such reforms on supply and demand conditions, and thus on the market position, solvency, and profit-making potential of his economic enterprise. The East European experience is a prime example of the enormous difficulty involved in salvaging apparently healthy enterprises once a change of economic system has taken place.

There is also a veritable maze of legal problems posed by the issue of the legality of foreign investments and the validity of property rights acquired during the Castro era. Obviously, both Cuban nationals and foreigners whose properties were confiscated during the early years of the revolution will reclaim them as soon as this becomes feasible. The United States, as well as other countries whose citizens’ assets were seized without adequate compensation, stand ready to support their nationals’ claims. Additionally, Cubans living in different parts of the world eagerly await the opportunity of exercising their legal rights before the Cuban courts in a post-Castro situation. Again, the East European example is a good indication of the complexities, delays, and uncertainties accompanying the reclamation process.

A different kind of problem is that posed by the legality of investments and the legitimacy of property rights relating to assets and facilities that did not exist before the Castro regime acceded to power. This, indeed, is an extremely sensitive and technically convoluted issue. It should be noted that exaggerated popular sentiments and a politically incendiary rhetoric will certainly await those who are now investing in Cuba. At the very least, they should expect to deal with a conflicted social climate and an adverse business environment. That is, at this time investors will invariably encounter an ambience in Cuba that is not conductive to productive operations.

As for the purely legal matter of the status of investment projects and contractual obligations entered into during Castro’s tenure of power, there is no dearth of scholarly opinions questioning their validity before a court of law. Under the precepts of international law, agreements subscribed to by usurping authorities and/or others that are clearly harmful and detrimental to the public good or commonwealth, or which violate the civil rights of the population (such as the case of forced or coerced labor), are considered null and void.

None of the above addresses a fundamental issue of extraordinary moral impact: lending assistance to a totalitarian regime that cruelly and callously has systematically violated the most elementary human rights of the Cuban population. The Cuban regime stands condemned by the United Nations and the Organization of American States as one among the few throughout the world that share that notoriety.

If investment and trade embargoes imposed in the past on those political systems that have been convicted of heinous crimes and abominable deeds against their populations have any sense and can claim to be morally justified, the case of Cuba must be among the most salient ones, symbolizing a country whose population has been uninterruptedly governed by a totalitarian regime for sixty-four years.

It is to be hoped that investors and entrepreneurs, cognizant of the drama of the Cuban people, will realize their ethical and moral obligations and abstain from lending success to a regime that will be harshly judged by history as well as by those who have been victimized by it.

*Jaime Suchlicki is Director of the Cuban Studies Institute, CSI, a non-profit research group in Coral Gables, FL. He is the author of Cuba: From Columbus to Castro & Beyond, now in its 5th edition; Mexico: From Montezuma to the Rise of the PAN, 2nd edition, and Breve Historia de Cuba.

https://cubanstudiesinstitute.us/principal/the-folly-of-investing-in-cuba/

Reuters, February 15, 20232:54 PM EST

Russia donates 25,000 tonnes of wheat to ally Cuba as ties deepen

By Mario Fuentes and Nelson Acosta

HAVANA, Feb 15 (Reuters) - Russia on Wednesday gave Cuba an "emergency" donation of 25,000 tons of wheat to combat shortages on the island, a sign of deepening ties between the two long-time allies.

The Russian ambassador in Havana, Andrei Guskov, said in a brief dockside ceremony in the Cuban capital that Moscow "accompanies Cuba's efforts in its development in areas such as industry, machinery, transportation and energy."

The substantial donation of wheat - used to make the bread that is a basic, government-subsidised staple in Cuba - marks the latest overture between the communist-run island and Russia.

Russia, hit by Western sanctions over the conflict in Ukraine, is looking to strengthen political and economic ties with other countries opposed to what it calls U.S. hegemony. Cuba has been under a U.S. economic embargo since 1962 after the Communist revolution led by Castro.

Ana Teresita González, Cuban deputy minister of foreign trade, told Reuters on the sidelines of the ceremony that the Russians had provided Cuba with food and medicine recently, part of an "enduring relationship" between the two countries.

"The Russian government and people have been by our side in difficult times since the pandemic," she said in a brief interview.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Cuban counterpart Miguel Diaz-Canel in November unveiled a monument in Moscow to Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro, pledging to deepen their friendship in the face of U.S. sanctions against both countries.

Days before invading Ukraine, Russia had also agreed to postpone debt payments owed by Cuba until 2027.

Cuban state-run media said in December the grains deliveries were part of 800 million rubles ($10.8 mln) earmarked by Russia to purchase and deliver wheat to Cuba.

Russia in April shipped 20,000 tonnes of wheat to Cuba as prices globally spiked early in the Ukraine conflict, prompting bread shortages on the island.

(Reporting by Mario Fuentes and Nelson Acosta in Havana, additional reporting by Alexander Frometa, editing by Dave Sherwood and Sharon Singleton)

https://www.yahoo.com/news/russia-donates-25-000-tonnes-191123968.html

From the archives

The New York Times, December 8, 2016

Americas

Cuba’s Surge in Tourism Keeps Food Off Residents’ Plates

By AZAM AHMED

HAVANA — For Lisset Felipe, privation is a standard facet of Cuban life, a struggle shared by nearly all, whether they’re enduring blackouts or hunting for toilet paper.

But this year has been different, in an even more fundamental way, she said. She has not bought a single onion this year, nor a green pepper, both staples of the Cuban diet. Garlic, she said, is a rarity, while avocado, a treat she enjoyed once in a while, is all but absent from her table.

“It’s a disaster,” said Ms. Felipe, 42, who sells air-conditioners for the government. “We never lived luxuriously, but the comfort we once had doesn’t exist anymore.”

The changes in Cuba in recent years have often hinted at a new era of possibilities: a slowly opening economy, warming relations with the United States after decades of isolation, a flood of tourists meant to lift the fortunes of Cubans long marooned on the outskirts of modern prosperity.

But the record arrival of nearly 3.5 million visitors to Cuba last year has caused a surging demand for food, causing ripple effects that are upsetting the very promise of Fidel Castro’s Cuba.

Tourists are quite literally eating Cuba’s lunch. Thanks in part to the United States embargo, but also to poor planning by the island’s government, goods that Cubans have long relied on are going to well-heeled tourists and the hundreds of private restaurants that cater to them, leading to soaring prices and empty shelves.

Without supplies to match the increased appetite, some foods have become so expensive that even basic staples are becoming unaffordable for regular Cubans.

“The private tourism industry is in direct competition for good supplies with the general population,” said Richard Feinberg, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, and specialist on the Cuban economy. “There are a lot of unanticipated consequences and distortions.”

There has long been a divide between Cubans and tourists, with beach resorts and Havana hotels effectively reserved for outsiders willing to shell out money for a more comfortable version of Cuba. But with the country pinning its hopes on tourism, welcoming a surge of new travelers to feed the anemic economy, a more basic inequality has emerged amid the nation’s experiment with capitalism.

Rising prices for staples like onions and peppers, or for modest luxuries like pineapples and limes, have left many unable to afford them. Beer and soda can be hard to find, often snapped up in bulk by restaurants.

It is a startling evolution in Cuba, where a shared future has been a pillar of the revolution’s promise. While the influx of new money from tourists and other visitors has been a boon for the island’s growing private sector, most Cubans still work within the state-run economy and struggle to make ends meet.

President Raúl Castro has acknowledged the surge in agricultural prices and moved to cap them. In a speech in April, he said the government would look into the causes of the soaring costs and crack down on middlemen for price gouging, with limits on what people could charge for certain fruits and vegetables.

“We cannot sit with our hands crossed before the unscrupulous manner of middlemen who only think of earning more,” he told party members, according to local news reports.

But the government price ceilings seem to have done little to provide good, affordable produce for Cubans. Instead, they have simply moved goods to the commercial market, where farmers and vendors can fetch higher prices, or to the black market.

Havana offers stark examples of this growing chasm.

At two state-run markets, where the government sets prices, the shelves this past week were monuments to starch — sweet potatoes, yucca, rice, beans and bananas, plus a few malformed watermelons with pallid flesh.

As for tomatoes, green peppers, onions, cucumbers, garlic or lettuce — to say nothing of avocados, pineapples or cilantro — there were only promises.

“Try back Saturday for tomatoes,” one vendor offered. It was more of question than a suggestion.

But at a nearby co-op market, where vendors have more freedom to set their prices, the fruits and vegetables missing from the state-run stalls were elegantly stacked in abundance. Rarities like grapes, celery, ginger and an array of spices competed for shoppers’ attentions.

The market has become the playground of the private restaurants that have sprung up to serve visitors. They employ cadres of buyers to scour the city each day for fruits, vegetables and nonperishable goods, bearing budgets that overwhelm those of the average household.

“Almost all of our buyers are paladares,” said one vendor, Ruben Martínez, using the Cuban name for private restaurants, which include about 1,700 establishments across the country. “They are the ones who can afford to pay more for the quality.”

By Cuban standards, the prices were astronomic. Several Cuban residents said simply buying a pound of onions and a pound of tomatoes at the prices charged that day would consume 10 percent or so of a standard government salary of about $25 a month.

“I don’t even bother going to those places,” said Yainelys Rodriguez, 39, sitting in a park in Havana while her daughter climbed a slide. “We eat rice and beans and a boiled egg most days, maybe a little pork.”

Mrs. Rodriguez’s family is on the lower end of the income ladder, so she supplements earnings with the odd cleaning job she can find. With that, she cares for her two children and an infirm mother.

Trying to buy tomatoes, she said, “is an insult.”

Another mother, Leticia Alvarez Cañada, described what it was like to prepare decent meals for her family with prices so high. “We have to be magicians,” she said.

The struggle is somewhat easier now that she is in the private sector and no longer working for the government, she said. She quit her job as a nurse to start a small business selling fried pork skin and other snacks from a cart. Now she earns about 10 times more every month.

“The prices have just gone crazy in the last few years,” said Mrs. Cañada, 41. “There’s just no equilibrium between the prices and the salaries.”

While many Cubans have long been hardened to the reality of going without, never more than during what they call the “Special Period” after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a new dynamic that has emerged in recent months threatens the nation’s future, experts warn.

“The government has consistently failed to invest properly in the agriculture sector,” said Juan Alejandro Triana, an economist at the University of Havana. “We don’t just have to feed 11 million people anymore. We have to feed more than 14 million.”

“In the next five years, if we don’t do something about it, food will become a national security issue here,” he added.

The government gives Cubans ration books to help provide staples like rice, beans and sugar, but they do not cover items like fresh produce. Tractors and trucks are limited and routinely break down, often causing the produce to spoil en route. Inefficiency, red tape and corruption at the local level also stymie productivity, while a lack of fertilizer reduces yield (though it keeps produce organic, by default).

Economists also argue that setting price ceilings can discourage farmers and sellers. If prices are set so low they cannot turn a profit, they argue, why bother working? Most will try to redirect their goods to the private or black market.

“From the point of view of the farmer, what would you do?” asked Dr. Feinberg, the California professor. “When the differentials are that great, it requires a really selfless or foolish person to play by the rules.”

Paladares sometimes go directly to farms to buy goods, and even provide farmers seeds for specialty products that do not ordinarily grow in Cuba, like arugula, cherry tomatoes and zucchini.

Most acknowledge that they distort the market in some ways, and this year the government stopped issuing licenses for new restaurants in Havana. But some restaurant owners argue that it is the government’s responsibility to create better supply.

“It’s true, the prices keep going up and up,” said Laura Fernandez, a manager at El Cocinero, a former peanut-oil factory converted into a high-priced restaurant. “But that’s not just the fault of the private sector. There is generally a lot of chaos and disorder in the market.”

On the outskirts of Havana, Miguel Salcines has cultivated a beautiful farm. Rows of tidy crops stretch toward the edge of his modest 25 acres, where he employs about 130 people.

Though he grows standard products on behalf of the government, there is no product he is more excited about than his new zucchini. A farmer for nearly 50 years, he had never grown the crop before, but planted a batch two months ago.

Now, the vegetables are coming into shape, the spots of bright orange flowers visible amid the green plumage. He knows this crop is not for the regular market, or for the government. It is like the arugula he grows.

It is for the tourist market and, by extension, the future.

“We are talking about an elite market,” he said. “The Cuban markets are a market of necessity.”

Hannah Berkeley Cohen and Kirk Semple contributed reporting from Havana, and Frances Robles from Miami.

A version of this article appears in print on December 9, 2016, on Page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: Cuba’s Surge in Tourism Is Keeping Food Off Its Residents’ Plates.

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/08/world/americas/cuba-fidel-castro-food-tourism.html