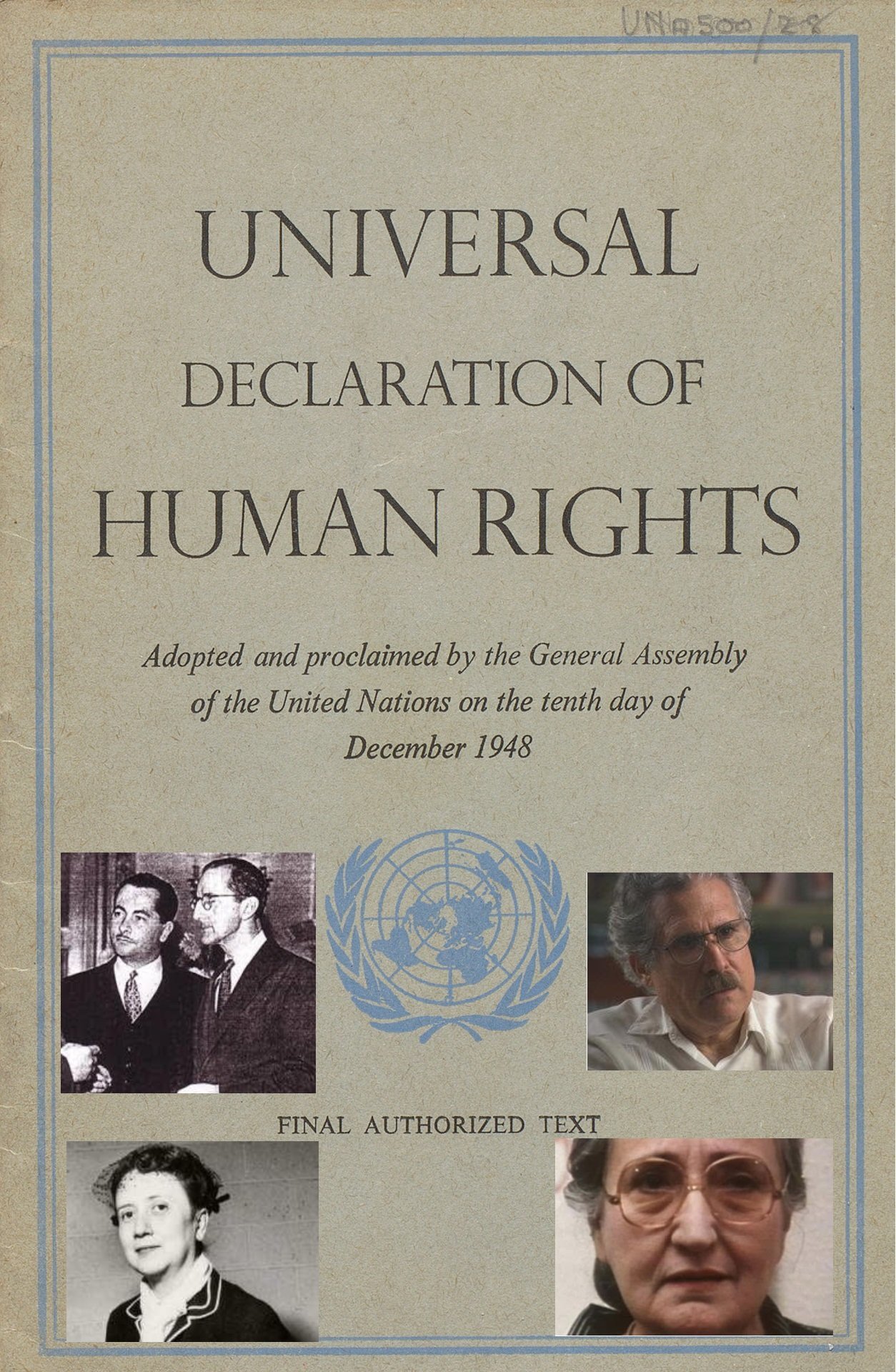

Gustavo Gutierrez Sanchez, Cuban architect of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Cuban dictatorship has a double discourse, one for the Cuban populace in the island, and another for the international community to justify its presence on the UN Human Rights Council, but its long term objective is to make the Universal Declaration of Human Rights irrelevant.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a prohibited document in the island. Cubans have been jailed for possessing copies of the Declaration that Cuban officials have called "enemy propaganda." Cuban children have been instructed to burn copies of the UDHR in an "act of repudiation" against the Ladies in White they were taken to by government officials.

Fidel Castro in a 1986 interview claimed that "[y]our political concepts of liberty, equality, justice are very different from ours. You try to measure a country like Cuba with European ideas. And we do not resign ourselves to or accept being measured by those standards." However the now dead Cuban dictator omitted that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was an initiative led by Latin Americans, and Cubans in particular. Furthermore that language placed in the Declaration was taken from the 1940 Cuban Constitution, or that Cubans lobbied for its passage in 1948, and Cuban diplomat Guy Perez Cisneros advocated for it, and celebrated its passage.

Meanwhile the Cuban regime uses official media to claim to celebrate human rights. Havana organizes events with other countries seeking to suppress human rights while claiming to promote them in their communications strategy for the international community while systematically repressing Cubans, and denying them their rights.

Havana has memory holed the history of Cuba's leading role in proposing, drafting, and lobbying for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights between 1945 and 1948. The names of Guy Perez Cisneros, and Gustavo Gutierrez Sanchez who broke new ground on the international human rights front were erased for decades.

Guy Pérez Cisneros (1915-1953)

In February 1945, with World War Two still underway, at the Chapultapec Castle in Mexico City twenty Latin American countries and a large delegation from the United States participated in the Inter-American Conference on Problems of War and Peace. Dr. Gustavo Gutierrez attended the conference, and presented on behalf of Cuba “two detailed proposals for consideration, a Draft Declaration of the International Rights and Duties of the Individual and a "Draft Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Nations." These two drafts were written by Dr. Gustavo Gutierrez in his book La Carta Magna de la Comunidad de Naciones. Later that year the Cuban delegation in San Francisco would present his draft for consideration in the creation of a universal declaration of human rights.

On December 10, 2017 in the Miami Herald's letters to the editor section, Pablo Pérez-Cisneros Barreto, the son of Guy Pérez-Cisneros y Bonnel, wrote of his family's and Cuba's legacy in drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

My late father believed that the declaration is the fruit of the great efforts of our civilization and human progress, a unique moment in which humanity came of age in its civic education; that it is also a source of inspiration for the formation of today’s citizens, and not cause for divisions among them. [...] Cuba had the distinction of being the country that proposed the finished declaration be put up for its final UN vote on Dec. 10, 1948. Hard to believe now but Cuba was once a leader when it came to human rights. And it is important to note that nine initiatives proposed in 1945’s Cuba became part of the final declaration, and that Cuba was the country that entrusted the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations in San Francisco to prepare the declaration as early as 1946. The third preamble of the declaration is a copy of one of the articles of the famed 1940 Cuban Constitution, and Cuba had the initiative to include in the declaration the right to honor one’s human rights and reputation, as well as protect citizens against arbitrary government interference in their private lives. Cuba presented the first amendment to the draft declaration which was accepted, adding the right of citizens of any member country to follow the vocation they choose. Cuba presented a second amendment which was also accepted — the right of every worker to receive an equitable and satisfactory payment for their work.

The Center for a Free Cuba is sharing the panel discussion held on International Human Rights Day in 2022 with three generations of Cuban human rights defenders to observe Cuba's human rights legacy, and how to recover it. Rosa Leonor Whitmarsh y Dueñas was born in the El Vedado quarter of Havana in the Republic of Cuba on May 9, 1930. She grew up in Cuba's Republic, lived its democratic high watermark between 1940 and 1952, and remembered the role played by Cuba in the passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Sebastián Arcos Cazabón was born thirty one years later in 1961 in Havana, and spent the first three decades of his life growing up in the Castro regime. Carolina Borrero and Yoel Suarez were both born in Cuba, a generation later. This conversation gives insights into the human rights situation in Cuba, and the legacy of the democratic Cuba that fought for the establishment of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and achieved it 75 years ago today.

This document continues to remain relevant and important today for humanity.

Mary Ann Glendon, an emerita law professor at Harvard who served as U.S. ambassador to the Holy See, explained why in her December 9th OpEd in The Wall Street Journal highlighted three historic reasons why the Universal Declaration for Human Rights remains important.

First, in 1948 political realists scoffed at the idea that mere words could make a difference. But by 1989 the world was marveling that a few simple words of truth—a few courageous people willing to call good and evil by name—could change the course of history. The Universal Declaration became the most prominent symbol of the great grassroots movements that hastened the demise of colonialism, brought down apartheid in South Africa, and helped topple the seemingly indestructible totalitarian regimes in Eastern Europe. Its nonbinding principles had more effect than the international covenants that were based upon it.

Second, religion played a large role in those transformative movements. As one of the lawyers who defended civil-rights workers in Freedom Summer 1964, I can testify that it was religious conviction that motivated many of us to follow Martin Luther King Jr. in the struggle to end legal segregation. The same was the case in freedom movements elsewhere.

Third, it wasn’t the great powers of the world but a coalition of less-powerful nations that assured that protection of human rights was included among the purposes of the U.N. Human rights weren’t a priority for the five big nations that became permanent members of the Security Council. When those big nations decided to found a new peace and security organization, their main concern was to assure the stability of frontiers and provide a means of settling disputes.

Conservatives were actively involved in the forging of this human rights consensus 75 years ago, and are needed today to engage and defend this legacy. David M. Kirkham, a Latter-day Saint and former diplomat, in DeseretNews on December 9, 2023 makes the conservative case for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

But it’s important to remember that early proponents of human rights believed these rights either originated with God or natural law. That helps explain the declaration’s emphasis on many vitally good principles, shared across the political and religious spectrum — from socialist nations to capitalist nations—as well as from many majority Muslim nations to Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish and Christian nations as well.

The premise of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” articulates the essential value of every human being. This aligns with my own personal religious convictions as a Latter-day Saint that children are born innocent, and also that we are all literal children of a God who is our Father.

And yet, some continue to see the declaration merely as a haven for extreme far-left and progressive ideas. True, a perilous but increasingly prevalent assumption from this ideological extreme is that human rights are mere social constructs, established by the presumed wishes of the people or worse yet by the powerful to subjugate those without power. But if people can create rights — as opposed to discovering them in the realm of enduring principles — then people can also take them away.

Rights important to persons of faith, such as freedom of religion and conscience, are jeopardized in a world that prioritizes social benefits over restraint and sacrifice. Hence the need for many more conservative voices in the human rights dialogue.

The defense of human rights presents an opportunity to hold accountable regimes that violate these rights. For example on November 14th members of civil society held a side event at the UN to call out the human rights violation of the Castro dictatorship in Cuba.

The Center also continues to gather signatures advocating for the expulsion of Cuba from the UN Human Rights Council, and as the examples of Libya, Russia, and Venezuela demonstrate this can be achieved.

Babalu Blog, December 10, 2023

The forgotten Cuban man who helped the Universal Declaration of Human Rights become reality

Today, on the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we remember Gustavo Gutierrez Sanchez, a Cuban you have likely never heard of but who was instrumental in its drafting. Gutierrez Sanchez was also very much involved in the writing of Cuba’s 1940 constitution, considered by many a masterpiece in democracy and freedom. Fidel Castro’s revolution promised a return to this constitution, but as history shows, the communist dictator could never accept the democracy and freedom part.

Via Notes from the Cuban Exile Quarter:

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the forgotten man, and Cuba’s human rights legacy

Seventy-five years ago on December 10, 1948 the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the UN General Assembly. In 2008 in commemoration of the 60th anniversary of this important milestone, Mary Ann Glendon, the United States Ambassador to the Holy See, highlighted Latin American and Catholic contributions to human rights, and made special mention of the contribution made by Cuba that was documented in a diplomatic cable.

“The principal leader of the Latin American group in 1948 was a charismatic young Cuban representative named Guy Perez Cisneros. His son, Pablo Perez-Cisneros, attended the conference and recounted his father’s contributions to the UDHR, noting the gap between the Cuba of his father’s day and the deplorable state of human rights under the present regime. The work of Guy Perez-Cisneros and other delegates was captured in a 12-minute video presentation featuring archival footage of Eleanor Roosevelt and Guy Perez-Cisneros’ UN speech in support of the UDHR.”

However, Perez Cisneros was not the architect of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and until The Washington Post journalist David Hoffman explored this chapter of Cuban history in his 2022 book, Give Me Liberty: The True Story of Oswaldo Payá and his Daring Quest for a Free Cuba, this information was only available in some archives, and obscure blogs.

Hoffman found that the 1940 Cuban Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and Article 88g of the 1992 Cuban Constitution that made the Varela Project possible were largely the result of one talented Cuban who over the course of his career had been a diplomat, jurist, and scholar, but you’ve never heard of him. In fact, he has been called the “forgotten man.”

His name was Gustavo Gutierrez Sanchez and he was born in Camajuani, in the Province of Santa Clara, Cuba on September 20, 1895, and he died in exile in Miami on July 17, 1959 at age 63. In 1916, at just 21 years of age he had obtained doctorates in Civil and Public Law, and became Assistant Professor of International Public Law in the University of Havana, and in 1919 became the department head at age 24.

Carlos Márquez Sterling, a Cuban historian and statesman who led the drafting of the country’s 1940 Constitution, in 1976 wrote an article in Diario de las Americas where he highlighted Gustavo Gutierrez’s role in the drafting of the 1940 Constitution.

“Gustavo had formed part of the Bicameral Commission which drafted the project of the Constitution and I can assure you that many of the institutions that later found expression in our original document were based on previous works created by Gustavo Gutierrez.”

Hoffman in “Give Me Liberty” reported that the 1940 Constitution had a provision that had been drafted years earlier by Gustavo Gutierrez, and became “Article 135, Section F, which provided that laws could be proposed by congressmen and senators, government officials, courts, – and by citizens. ‘In this case,’ the constitution declared, ‘it will be an indispensable prerequisite that the initiative be exercised by at least ten thousand citizens having the same status of voters.”

The Cuban jurist believed that this clause would have given Cuban citizens a voice in public affairs that could have acted as a brake on Machado’s slide into dictatorship, or led to an earlier repeal of the Platt Amendment, or prevented Batista becoming a strong man. This provision somehow was recycled into the 1992 Cuban Constitution, and was the basis for the Project Varela that challenged totalitarian rule in Cuba beginning in 2002.

Continue reading HERE.

The Wall Street Journal, December 8, 2023

There’s Life Yet in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

In the face of war and atrocities, the principles of the 75-year-old document remain sound

By Mary Ann Glendon

Dec. 8, 2023

The United Nations General Assembly approved the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on Dec. 10, 1948, without a single dissenting vote (although Saudi Arabia, South Africa and the Soviet bloc countries abstained). Today that remarkable consensus, achieved in the wake of two world wars and unspeakable atrocities, is falling apart. Hope for global consensus on anything seems remote.

But is it really the case that consensus on the relatively small set of fundamental principles in the Universal Declaration can’t be reinvigorated? The history of the declaration suggests three reasons why the effort is worthwhile. And a promising development, as yet little noticed in the West, indicates there may be a fourth.

First, in 1948 political realists scoffed at the idea that mere words could make a difference. But by 1989 the world was marveling that a few simple words of truth—a few courageous people willing to call good and evil by name—could change the course of history. The Universal Declaration became the most prominent symbol of the great grassroots movements that hastened the demise of colonialism, brought down apartheid in South Africa, and helped topple the seemingly indestructible totalitarian regimes in Eastern Europe. Its nonbinding principles had more effect than the international covenants that were based upon it.

Second, religion played a large role in those transformative movements. As one of the lawyers who defended civil-rights workers in Freedom Summer 1964, I can testify that it was religious conviction that motivated many of us to follow Martin Luther King Jr. in the struggle to end legal segregation. The same was the case in freedom movements elsewhere.

Today, the role of religion is more complicated. Recent years have seen a rise in regional conflicts that implicate religion and a decline in religious affiliation in the West. That is a bad combination because religious zeal doesn’t necessarily disappear when it ceases to be directed toward religious objects. It is often transferred to some other object, such as ethnic identity, and pursued with deadly dedication.

Fortunately, however, it isn’t beyond the power of religious leaders and groups to reject ideologies that manipulate religion for political purposes or use it as a pretext for violence. Nor is it beyond their capacity to find resources within their own traditions for promoting respect and tolerance, as the Catholic Church did in Vatican II and as the world’s largest Muslim political organization, Nahdlatul Ulama, is doing today. Humanitarian Islam, the inclusive, tolerant form of Islam promoted by that 100-million-member group, has real potential to shift the probabilities for peace in many parts of the world.

Third, it wasn’t the great powers of the world but a coalition of less-powerful nations that assured that protection of human rights was included among the purposes of the U.N. Human rights weren’t a priority for the five big nations that became permanent members of the Security Council. When those big nations decided to found a new peace and security organization, their main concern was to assure the stability of frontiers and provide a means of settling disputes.

But at the founding conference, delegates from lesser powers—such as Herbert Evatt of Australia, Charles Malik of Lebanon and Carlos Romulo of the Philippines—joined forces to expand that agenda. The language of the U.N. Charter became the foundation of the entire postwar human-rights project.

Today as in 1945, the most intense interest in the idea of universal human rights seems to be among nations and political groups that don’t exert the most influence on the world stage—but that understand that without commitment to a few basic principles, nothing is left but the will of the stronger.

The Center for Shared Civilizational Values, founded by the Indonesia-based Nahdlatul Ulama, wants to build a movement to strengthen a rules-based international order grounded in universal principles. Joining in that endeavor is the world’s largest network of political parties, Centrist Democrat International, composed mostly of European and Latin American political parties. In 2020 both organizations called for renewed global support of the human-rights principles in the Universal Declaration. That East-West collaboration is evidence that the core principles of the Universal Declaration have foundations in most of the world’s great philosophical and religious systems.

None of this would have surprised the men and women who brought the postwar human-rights project to life. They had seen human beings at their best and worst. But while the human race is capable of gross violations of human rights, it is also capable of imagining that there are rights to violate and articulating those rights in declarations and constitutions. People can orient their conduct toward the norms they recognize and feel the need to make excuses when their conduct falls short.

Seventy-five years ago, these visionaries forged a consensus that helped millions achieve better standards of life and greater freedom. Before giving up on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we should ask: Is it really going to take more wars, and more horrors, to breathe new life into a few enduring principles of human decency?

Ms. Glendon is an emerita law professor at Harvard. She served as U.S. ambassador to the Holy See, 2008-09.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/theres-life-yet-in-the-universal-declaration-of-human-rights-460a2be3

DeseretNews, December 9, 2023

The conservative case for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

A Latter-day Saint former diplomat explains why people of faith and conservatives should observe and honor human rights day this weekend.

By David M. Kirkham

Dec 9, 2023, 11:26pm EST

Hostages in Gaza, civilian casualties, war refugees from Ukraine, Christians persecuted in Egypt, Yezidis tortured in Iraq — these, the tired, poor and huddled of this world, share this salient feature: their dignity as human beings has been violated and torn from them.

A more widespread respect for human rights would go far to prevent such tragedies. Yet as we arrive at the 75th anniversary of the global adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights this weekend, too many aren’t sure whether they should even celebrate Human Rights Day, on Sunday, Dec. 10.

As defined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, human rights are “rights inherent to all human beings, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status.” They protect each and every one of us, just by virtue of our being human. We don’t earn them; they are not granted by governments. They are inherently, intrinsically and inalienably ours.

Even so, it’s not uncommon for Americans to ignore or even condemn this universal declaration. To some, it may seem simply ineffective as legally nonbinding. And since the beginning of its 75-year existence there’s little to suggest it’s saved us from ourselves. Furthermore, some religious believers may see religious teachings as transcending human rights, making them redundant. Political conservatives, meanwhile, sometimes see principles of American constitutional law as trumping the international statement of rights, while worrying about socialist undertones in purported economic rights.

This is understandable. After all, higher spiritual laws can seem to make secular statements of rights superfluous — especially when governments can never guarantee all of the declaration’s social and economic rights. And what about duties or responsibilities? Aren’t they as important as rights?

But it’s important to remember that early proponents of human rights believed these rights either originated with God or natural law. That helps explain the declaration’s emphasis on many vitally good principles, shared across the political and religious spectrum — from socialist nations to capitalist nations—as well as from many majority Muslim nations to Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish and Christian nations as well.

The premise of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” articulates the essential value of every human being. This aligns with my own personal religious convictions as a Latter-day Saint that children are born innocent, and also that we are all literal children of a God who is our Father.

And yet, some continue to see the declaration merely as a haven for extreme far-left and progressive ideas. True, a perilous but increasingly prevalent assumption from this ideological extreme is that human rights are mere social constructs, established by the presumed wishes of the people or worse yet by the powerful to subjugate those without power. But if people can create rights — as opposed to discovering them in the realm of enduring principles — then people can also take them away.

Rights important to persons of faith, such as freedom of religion and conscience, are jeopardized in a world that prioritizes social benefits over restraint and sacrifice. Hence the need for many more conservative voices in the human rights dialogue.

Consider four other reasons why moderate and conservative-minded persons and people of faith ought to sustain and celebrate these human rights efforts on the international stage:

1. A common moral starting point. In negotiations among peoples and governments over some of the most intractable problems of our time, we don’t all share the same religion, but nonbelievers and believers alike have come to agree in this declaration on such important points as people should not be subject to torture or deprived of their liberty without due process of a fair and humane legal system. A mutual respect for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its provisions can unite peoples with differing perspectives and agendas over common problems.

2. Religious freedom protection outside potentially corrupt regimes. Authoritarian regimes dictating who can worship, when, where and how, and deciding the consequences for nonconformism, pose a serious threat to believers in many parts of the world. The American Constitution, for all its inspired value, provides no protection to minority faiths, including Latter-day Saint congregations and missionaries, outside the United States. In many countries it is only laws derived from the principles of religious freedom found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that allow believers to meet, profess and live their faith.

This kind of protection can only be guaranteed when believers stay engaged in the process of defining, implementing and enforcing rights. Nonparticipants don’t get to make the rules. Faith communities need some recognition of human rights to fulfill their purposes. We ignore these rights at our peril.

3. Rights imply responsibilities. In a world where victimhood claims abound, many rightly point to the value of emphasizing responsibilities alongside rights. What they may not realize is that most human rights observers agree that each human right provision of the declaration implies a logically irrefutable, corresponding duty. If I have a right not to be tortured, governments and my fellow human beings have an accompanying responsibility to refrain from torturing. To maintain this equal emphasis on duties and rights, wise people need to remain engaged in the conversation.

4. Resolution of conflicting rights. Although human rights specialists assert that we can’t pick and choose which rights to support and prioritize, all serious observers know that there are times when rights contradict each other and need to be reconciled. Again, political conservatives might want to have a voice in how these contradictions are to be resolved.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a living document, subject to continued interpretation. It is widely acknowledged on the international stage as a fair statement of humanity’s aspirations, even by regimes with opposing interests. Like it or not, the declaration is here to stay. And thankfully, the spirit of the document suggests that persons of every political persuasion should respectfully participate in the ongoing interpretation of what human rights mean for our societies.

While the world’s many abuses against our brothers and sisters cry out to us for prevention and eradication, it’s significant that, since the adoption of the declaration, most “flagrant and repeated instances of rights abuse now are brought to light,” as Harvard law professor Mary Ann Glendon states, “and most governments now go to great lengths to avoid being blacklisted as notorious violators.”

When properly implemented, the modern human rights agenda helps bring to light all the hidden things of darkness in today’s tyrannical and lawless regimes. Again, having a voice in the process can make sure the discussion benefits from the values of people of faith.

Latter-day Saints in particular have something unique to offer here — in their conviction that the “worth of a soul is great” and that all human beings have a divine potential to become more like God. This is a very lofty understanding of human dignity indeed. My mention last year at an interfaith event in the United Arab Emirates that our church teaches even children about our divine nature brought approval and respectful inquiries by attendees. We have them singing “I am a child of God” from the moment they can croon a tune, I explained.

One BYU student participating in a European human rights study abroad program reflected on the ministry of Christ as she learned about human rights violations: “When Jesus atoned for us and felt all our pains, it was for all of us. That includes refugees and victims of sexual assault, discrimination and genocide. It made me think that it’s our duty to do what we can to help these people.”

Conservative or not. Religious or not. Human rights must be protected for everyone.

David M. Kirkham has been a Senior Fellow for Comparative Law and International Policy at the BYU Law School International Center for Law and Religion Studies since 2007, and is the new p

https://www.deseret.com/2023/12/9/23991303/conservative-case-universal-declaration-of-human-rights

Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, November 28, 2023

Can Cuba’s Democratic Legacy Be Recovered?

By John Suarez

Communist Cuba underwent its fourth Universal Periodic Review (UPR) on November 15, 2023, at the UN Human Rights Council, a process Havana repeatedly subverted since 2009 by using front groups to drown out critical human rights reports by established human rights organizations.

Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez began the UPR session attacking Israel, went on to blame the Cuban dictatorship’s shortcomings on U.S. sanctions, and turned the review into a politicized circus.

Over 20 years, I’ve witnessed Cuban diplomats undermine international human rights standards, first at the United Nations Human Rights Commission and later at the UN Human Rights Council, making a mockery of human rights.

On April 15, 2004 when the UN Human Rights Commission decided by a single vote to censure Cuba for its human rights record, a Cuban human rights defender attending the session, Frank Calzon, was physically attacked by a Cuban diplomat.

On March 28, 2008 the Castro regime’s delegation, together with the Organization of Islamic Congress, successfully passed resolutions that turned the UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression into an investigator policing “abuses” of freedom of expression.

On Feb. 2, 2009 during the Universal Periodic Review of China, Cuban Ambassador, Juan Antonio Fernandez Palacios, recommended that China repress human rights defenders with more firmness.

On March 17, 2014 at the UN Human Rights Council, Cuban diplomats defended the North Korean regime’s human rights record.

On Sept. 21, 2018 Cuban Ambassador to the UN, Pedro Luis Pedroso Cuesta, during the Universal Periodic Review on Cuba at the UN Human Rights Council stated that “our country will not accept monitors. Amnesty International will not enter Cuba and we do not need their advice.” Less than a month later, Cuban diplomats led an “act of repudiation“ at the UN shutting down a discussion on political prisoners in Cuba.

On July 1, 2020 the Cuban dictatorship introduced a resolution at the UN Human Rights Council endorsing the death of a free Hong Kong and praising China for passing the Hong Kong National Security Law.

What the diplomats of Cuba’s communist dictatorship do in Geneva is horrible, but it pales compared to what they do to Cubans on the island.

Human rights defenders Oswaldo Payá and Harold Cepero were killed on July 22, 2012. On June 12, 2023, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights confirmed that the two Cuban pro-democracy leaders were assassinated by Castro regime operatives.

On July 11, 2021 when Cubans across the island protested in huge numbers called for freedom, and an end to dictatorship. Raul Castro’s hand picked president, Miguel Díaz-Canel went on national television and gave the “order of combat.” Regime agents opened fire on unarmed Cubans, the number killed remains unknown due to regime repression, and lack of transparency, but the video of 36 year old singer Diubis Laurencio Tejeda shot in the back by police, and dying in his friends’ arms is devastating.

Artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and Maykel “Osorbo” Castillo Pérez are imprisoned in Cuba today for authoring a song about “homeland and life.” The dictatorship has severely restricted artistic freedoms, passed laws outlawing criticism of the regime on the internet, and passed an even more draconian penal code that expands the death penalty.

Human rights defenders Felix Navarro and his daughter Sayli Navarro, who sought to ascertain the plight of detained Cuban protesters, were themselves arrested and sentenced to long prison terms. There are over 1,000 prisoners of conscience in Cuba.

It was not always this way.

A democratic Cuba helped draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 75 years ago. Carlos Prío Socarrás, Cuba’s last democratic president, was elected in free and fair elections and took office on October 10, 1948. President Prío valued human rights, as seen by the activities of his diplomats during the United Nations’ founding.

Cuba, Panama, and Chile were the first three countries to submit full drafts of human rights charters. Latin American delegations, especially Mexico, Cuba, and Chile inserted language about the right to justice into the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in what would become Article 8.

Cuban delegate Guy Pérez-Cisneros addressed the UN General Assembly on December 10, 1948 proposing to vote for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Cuban Ambassador celebrated that it condemned racism and sexism, and addressed the importance of the rule of law:

“My delegation had the honor of inspiring the final text, which finds it essential that the rights of man be protected by the rule of law, so that man will not be compelled to exercise the extreme recourse of rebellion against tyranny and oppression.”

Fulgencio Batista overthrew this democratic Cuba on March 10, 1952, Guy Pérez-Cisneros died of a stroke in 1953, and hopes for democratic restoration were dashed by the Castro brothers in 1959 when they imposed a communist dictatorship.

This shared democratic Cuban heritage that in 1948 made world history must be restored, and Cuban communism dumped on the garbage heap of history.

John Suarez is Executive Director of the Center for a Free Cuba.

https://victimsofcommunism.org/can-cubas-democratic-legacy-be-recovered/