Senator Marco Rubio and Congressman Mario Diaz-Balart have taken the lead in calling out personnel cuts at the Office of Cuba Broadcasting (OCB). On July 13, 2021, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro N. Mayorkas spoke about U.S. Maritime Migrant Interdiction Operations at a Department of Homeland Security press briefing warning Cubans and Haitian: “Allow me to be clear: If you take to the sea, you will not come to the United States.” This message would have been more effective if it were more widely heard in Cuba, but the Office of Cuba Broadcasting, which includes Radio Martí, continues to be gutted in the midst of the largest Cuban exodus since 1959.

The Center for a Free Cuba has prepared a report on the budget cuts and reduction in personnel of Radio Martí and the programming in Chinese of the Voice of the Americas (VOA) at a time when crises with both Cuba and China, including threats against Taiwan, are increasing.

“I am appalled by the Biden admin’s shameful decision to begin a “Reduction in Force” at the OCB,” Diaz-Balart

In the Cuban case, street protests continue to break out across the island, despite continuing repression. In addition, tens of thousands of Cubans are on dangerous journeys to enter the United States. The report finds that this trend has been ongoing for some time, but the present moment demands more, not less public diplomacy through channels that will reach more Cubans directly, and that Havana will find more difficult to shut down or jam.

The Cuban dictatorship, and their agents of influence attempt to deflect responsibility for causing the exodus, and weaponizing it but the facts say otherwise. Consider the following.

Failures in Agriculture

Tons of fish rotting in Cuba in the midst of scarcity due to government inefficiencies..

The Washington Post published on August 25, 2022 the Associated Press article "Reforms help Cuban farmers, but many still struggle" by Andrea RodrÍguez, who is based in Cuba. She reproduces the official line in the article that shifts blame away from the dictatorship, but experts outside of Cuba offer a more accurate analysis.

“Before the 90s, Cuba had all the resources (supplied by Soviet Bloc allies) and the results were bad,” said Ricardo Torres, a Cuban economist at the Center for Latin American Studies at American University in Washington.He said problems include overly centralized administration and state ownership of most land — something imposed in years soon after the 1959 revolution, which nationalized big foreign owned farms and later smaller local ones. Most farmers have rights only to use the land they farm, not to own it, which outside experts say limits their incentive to invest in it.

This was not always the case. According to the Cuban Studies Institute between 1952-1958 there was "a successful nationalistic trend aimed to reach agricultural self-sufficiency to supply the people’s market demand for food." Despite the efforts to violently overthrow the Batista regime in the 1950s, "the Cuban food supply grew steadily to provide a highly productive system that, in daily calories consumption, ranked Cuba third in Latin America."

This ended when the Castro regime seized and collectivized properties, and prohibited farmers selling their crops to non-state entities, in the early years of the revolution. Farmers no longer decided how much to produce, or what price to sell. The Cuban government established production quotas and farmers were (and are) obligated to sell to the state collection agency, called Acopio. Recent laws on agriculture in Cuba, such as ( Decreto Ley 358 de 2018), continued to prohibit private sales of agricultural products to non-state entities. The dictatorship began rationing food in 1962 as a method of control and continues the practice to the present day. Rationed food is not free, but sold at subsidized prices. Rationed items are not enough to feed a person. In 2021 the regime attempted to change their agricultural policy, but it was cosmetic because officials are still wedded to communism, and cannot permit true market reforms.

Healthcare in tatters

On the healthcare front the system is also in tatters. The death of Cuban General Luis Alberto Rodríguez López-Calleja, chief administrator of GAESA, and former son-in-law to Raul Castro on July 1, 2022 presents several problems for the regime. First, he had played and was supposed to continue to have a role in Raul Castro's succession plans. Second, it appears that he died of lung cancer, but this has been shrouded in secrecy, in part because Havana claims to have developed a vaccine against lung cancer that they have widely touted. Since 2008 they have used this claim as a propaganda talking point for their claims to superior healthcare in Cuba, and have set up an online presence encouraging patients to go to Cuba for treatment.

Failed COVID-19 response

Cuban government officials decided early on in the COVID-19 pandemic that they wanted to be “be the first country in the world to vaccinate their whole population with their own vaccines,” and were willing to let Cubans die while they developed their domestic vaccines instead of importing them, including from their allies Russia and China in order to advance their “healthcare superpower” narrative.

The Economist on August 3, 2022 published “Covid-19 has damaged the reputation of Cuban health care: The country’s once-famed health system is in tatters.” In the United States, which had well publicized challenges and failures during COVID-19, excess deaths were 354/100,000. While Cuba, which was touted as a success story, had a far worse outcome than the United States with 550/100,000 excess deaths. Costa Rica, by comparison, had better outcomes than both Cuba and the United States with 194/100,000 excess deaths.

Obstetric violence in Cuba

Havana Times on August 25, 2022 published the article "How Cuba’s Authoritarian System Enables Obstetric Violence" written by Partos Rotos, a collaboration by Cuban journalists that begins with a description of what one Cuban woman went through.

On August 12, 2015, at two in the afternoon, Paloma López called the ambulance that would take her to Ramón González Coro, an OB-GYN hospital in Havana. Early that morning, she decided to start her labor at home, as she had heard about women being ill-treated at the hospital. When she arrived, she was six centimeters dilated but her water had not broken. “They took me to the gurney to monitor me, they lifted me and took me to a strange room. Then, without any warning, (the doctor) took out a pointy object, and bam! She stuck it in me, and it hurt. I screamed, ‘what is that!’, and it broke my water.” The obstetrician threw all her weight on Paloma’s stomach and used her forearm to press on the uterus to push the baby down. Paloma was startled and struck away the doctor’s hand. As she was leaning on her with her feet practically up in the air, the doctor fell to the floor. “Look at this bitch, she doesn’t want to be helped! She’s going to kill the baby,” Paloma recalls the doctor shouting. “Doctor, don’t say that! You have to ask me for permission.” “No, you don’t have a clue.”

The rest of the article outlines the systemic nature of obstetric violence in Cuba. Beyond psychological abuse visited upon the prospective mothers there are also negative physical consequences according to Havana Times.

For some, the problem was that they suffered excessive medicalization or aggressive practices. One of these practices is known as the Kristeller maneuver, which involves applying manual pressure on the ribs and has been questioned by the WHO since 1996. Another common procedure is called an episiotomy. It is performed by making an incision in the perineum, a tissue located between the vagina and the anus, to facilitate childbirth. This is often performed without consent and/or when it is not required.

Katherine Hirschfeld, an anthropologist, in Health, Politics, and Revolution in Cuba Since 1898 described how her idealistic preconceptions were dashed by 'discrepancies between rhetoric and reality.' She observed a repressive, bureaucratized and secretive system, long on 'militarization' and short on patients' rights.

Luis Pablo de la Horra in an article published by the Foundation for Economic Education titled "Why Cuba's Infant Mortality Rate Is So Low" answers the question in the subtitle that "Cuba’s impressive infant mortality rate has a simple explanation: data manipulation" and provides a more detailed explanation that is reproduced below.

"In a 2015 paper, economist Roberto M. Gonzalez concluded that Cuba’s actual IMR is substantially higher than reported by authorities. In order to understand how Cuban authorities distort IMR data, we need to understand two concepts: early neonatal deaths and late fetal deaths.

The former is defined as the number of children dying during the first week after birth, whereas the latter is calculated as the number of fetal deaths between the 22nd week of gestation and birth. As a result, early neonatal deaths are included in the IMR, but late fetal deaths are not. For the sample of countries analyzed by Gonzalez, the ratio of late fetal deaths to early neonatal deaths ranges between 1-to-1 and 3-to-1.

However, this ratio is surprisingly high in Cuba: the number of late fetal deaths is six times as high as that of early neonatal deaths. This number suggests that many early neonatal deaths are systematically reported as late fetal deaths in order to artificially reduce the IMR. Gonzalez estimates that Cuba’s true IMR in 2004, the year analyzed in the paper, was between 7.45 and 11.46, substantially higher than the 5.8 reported by Cuban authorities, and far worse than the rates of developed countries."

Daniel Raisbeck and John Osterhoudt at Reason on Monday April 18, 2022 premiered a documentary on "The Myth of Cuban Health Care" that is required viewing.

Not mentioned in their documentary is that other Latin American countries ( Costa Rica, and Chile ) rate higher than the U.S. on international indices with regards to their healthcare systems, but are rarely mentioned as models to emulate. Despite Cuba's unreliable and inflated statistics, its health care system still rates lower than the United States.

Failing Infrastructure

Hotel Saratoga explodes on May 6, 2022 killing over 40 Cubans and tourists

On May 6, 2022 the historic Hotel Saratoga exploded and over 40 Cubans were killed in what officials said was caused by a gas leak, It was managed by the military-owned Gaviota tourism company.

Cuban voices were declaring Cuba a failed state in the midst of a major fire at the Matanzas Supertanker Base that began on August 5, 2022 and over the next four days has spread out of control engulfing four tanks at the storage facility.

Matanzas Supertanker Base caught fire on August 5, 2022 following a lightning strike.

In the midst of the unfolding disaster, the Cuban government continued with a focus on optics and propaganda, in some cases delaying help to confront the raging fire. Stephen Gibbs, the Latin American correspondent for The Times tweeted on August 7th, “Mexican firefighters arrive in Cuba. Are the speeches really necessary? Isn’t this an emergency?”

Case study on relationship between lack of freedoms and failures to address social problems

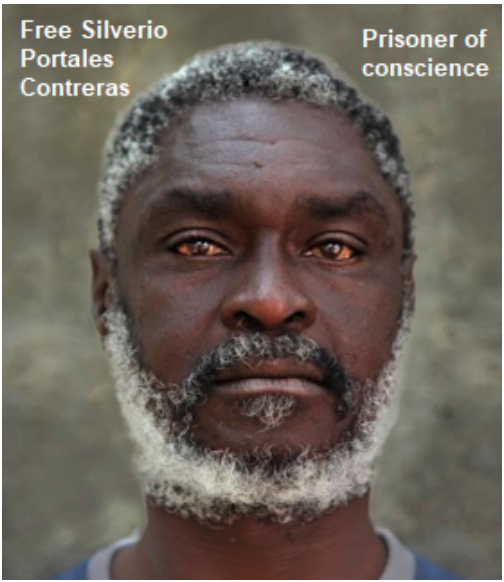

Silverio Portal Contreras jailed for four years for protesting against dilapidated buildings.

Silverio Portal Contreras was sentenced to four years in prison for alleged crimes of "public disorder" and "contempt" after leading several public protests demanding decent housing for all Cubans. He was detained on June 20, 2016 in Havana, and the court document states that "the behavior of the accused is particularly offensive because it took place in a touristic area." The document further describes the accused as having "bad social and moral behavior" and mentions that he fails to participate in pro-government activities. According to Silverio’s wife, before his arrest he had campaigned against the collapse of dilapidated buildings in Havana. Silverio was recognized as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International on August 26, 2019. He was beaten by prison officials in mid-May 2020 and lost sight in one eye.

Regime officials, who jailed Silverio, did not heed his warnings regarding dilapidated buildings. On January 27, 2020, three schoolgirls died when a balcony collapsed on them in Old Havana. María Karla Fuentes and Lisnavy Valdés Rodríguez, both 12 years old, and Rocío García Nápoles, 11 years old, were killed.

How can one expect society to improve when dissent is punished, and an independent press with a critical eye illegal? The example of Cuba over the past 63 years demonstrates that one cannot expect improvement. Propaganda claims yes, but actual improvement no. This is part of the message that Voice of America and the Office of Cuba Broadcasting should be sharing widely with the Cuban people, but massive cutbacks are reducing their impact.

Florida Daily, August 26, 2022

Mario Diaz-Balart Opposes Biden’s Plan to Reduce Personnel in Office of Cuba Broadcasting

By Kevin Derby - August 26, 2022, 2:00pm

This week, a Florida congressman called out the Biden administration for stripping funds from the Office of Cuba Broadcasting (OCB).

U.S. Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart, R-Fla., who has been in Congress for more than two decades and sits on the U.S. House Appropriations Committee, weighed in on the proposal to lower the budget of the OCB.

“I am appalled by the Biden administration’s shameful decision to begin a “Reduction in Force” (RIF) at the Office of Cuba Broadcasting (OCB),” Diaz-Balart said.

“For years now, USAGM has requested roughly $13 million for OCB, despite OCB’s usual annual budget of roughly $30 million in previous fiscal years. USAGM continues to blame Congress for the cuts, and certainly, the Democrat majority shares a large part of the blame. Yet to date, I have yet to receive an explanation as to why USAGM continues to request such an abysmally low number for OCB year after year while fully knowing the consequences. In fact, USAGM has not affirmed whether it is initiating these layoffs due to the administration’s plans for ‘reform’ or due to its requested budget cuts. In fact, in recent fiscal years, Congress has provided transfer authorities to shore up OCB and prevent layoffs. Nonetheless, the Biden administration is irresponsibly barreling ahead with devastating firings — just before the holidays — based on scant justification,” he added.

Diaz-Balart said OCB continues to help opponents of the Cuban regime.

“As we recently marked the one-year anniversary of the protests on July 11, hundreds of political prisoners remain imprisoned in Cuba, including several children. Diminishing this crucial source of outside, objective information at this time is an insult to the heroes who continue to risk their lives for freedom. It shows once again that the Biden administration is failing them in order to appease the communist oppressors. The Biden administration and USAGM should abandon this despicable attempt to weaken OCB before they cause irreparable harm, and finally stand with the Cuban people at a time when they need it most,” the congressman said.

Diaz-Balart faces community activist Christine Olivo, who is the Democratic Party’s candidate, in November. Diaz-Balart starts the race as a solid favorite in a strong Republican district.

The Washington Post, August 25, 2022

Reforms help Cuban farmers, but many still struggle

By Andrea RodrÍguez | AP

August 25, 2022 at 10:39 a.m. EDT

A farmer’s shadow is cast on the curtain of a tomato greenhouse at the Vista Hermosa farm in Bacuranao, just east of Havana, Cuba, Thursday, Aug. 4, 2022. A package of 63 reforms approved last year was meant to make it easier and more profitable for Cuban producers to get food to consumers. Farmers say the measures are still not sufficient to overcome obstacles. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

HAVANA — First, it was impossible to find fuel or seeds to plant. Later his name wasn’t on a list of farmers eligible to rent tractors from the state. Now Lázaro Sánchez fears the current tropical rainy season will hinder his ability to work the land.

While Sánchez worries about trying to grow crops at his farm on the outskirts of Havana, Cubans in the cities are struggling with shortages of food and soaring prices.

To address such problems, Cuba’s socialist government last year approved a package of 63 reforms meant to make it easier and more profitable for producers to get food to consumers — measures such as allowing farmers greater freedom to choose their crops and letting them sell more freely, at higher prices.

They are the latest in a series of highly touted changes adopted over the past 30 years since the collapse of the Soviet Bloc stripped Cuba of its most important sources of aid and trade. Officials have eroded the dominance of state farms and encouraged more semi-independent cooperatives. They have given farmers greater land use rights and loosened restrictions on sales.

But none of those efforts has yet been able to solve the island’s chronic agricultural woes.

Sánchez, for example, can now sell most of the vegetables he produces himself instead of being forced to sell them to the state at fixed prices, though it still takes a reduced share. He could even set up his own roadside stand if he chooses. His power and water bills have been cut.

But farmers say the measures are still not sufficient to overcome obstacles. While government prices for some supplies such as local herbicides, fertilizers, wire and tools were cut, many inputs remain hard to get. The state is trying to overcome a lack of resources needed to import them.

The shortage of fruits in a tropical nation and of pork that is basic to the Cuban diet has become even more dire due to hardships caused by a pandemic that choked off the revenue-producing tourism industry — and by economic sanctions tightened under former U.S. President Donald Trump.

And Sánchez said the problems he encountered mean his own farm won’t do much to solve the problem this season.

“Sadly, we are going to be affected in three or four months. The food we had to be planting we’re not going to have,” Sánchez told The Associated Press.

The 56-year-old Sánchez and his brother work a 26-hectare (64-acre) farm that usually produces crops such as squash, corn, bananas, small animals and the tuber called malanga that is widely eaten in Cuba.

The island spends about $2 billion a year of its scarce foreign currency importing foods — though authorities say about $800 million of that could be produced at home under the right conditions.

Cuba’s National Statistics and census Office reported production of 2.1 million tons of tubers — such as potatoes and malanga — last year, about the same as in 2020 but short of the 2.8 million produced in 2017.

Cuba’s farms produced 1.7 million tons of vegetables — down from 2.4 million in 2017. Output of rice, corn, beans and citrus also has been stagnant or declining, as has that of milk, pork and beef.

And that has slammed Cubans in the pocketbook at a time when many other prices are rising as well.

A pound of pork that sold for 100 Cuban pesos ($4.10) last year now goes for 300 ($12.50). An avocado that cost 20 pesos (80 cents) now is 60 ($2.50). A monthly wage averages about 4,000 pesos ($160).

Still, authorities defend the reforms, saying that without them, things would have been even worse.

“The 63 measures have had a favorable impact,” said Armando Miralles, the Agriculture Ministry’s director of organization and information. He said it was an achievement to avoid even sharper losses, given the economic woes.

Outside experts, however, say other factors are to blame as well.

“Before the 90s, Cuba had all the resources (supplied by Soviet Bloc allies) and the results were bad,” said Ricardo Torres, a Cuban economist at the Center for Latin American Studies at American University in Washington.

He said problems include overly centralized administration and state ownership of most land — something imposed in years soon after the 1959 revolution, which nationalized big foreign owned farms and later smaller local ones. Most farmers have rights only to use the land they farm, not to own it, which outside experts say limits their incentive to invest in it.

Cuban officials say most potential farmland remains uncultivated despite a series of efforts to encourage people to leave the cities and take up the plow.

“When they launched the 63 measures, in that moment it was an achievement,” said Misael Ponce, who has 120 hectares (297 acres) dedicated to ranching in addition to a small plant producing cheese and yoghurt he sells to hotels — a business allowed under the new measures.

But he said the new income has been eaten by inflation. While the state tripled the price of milk, the cost of inputs rose by eight times, he said. “It is something that has to be reviewed very quickly,” he said.

Havana Times, August 25, 2022

How Cuba’s Authoritarian System Enables Obstetric Violence

Cuba’s childbirth care system prioritizes infant mortality statistics but ignores quality indicators and humanized childbirth practices.

By Partos Rotos, a collaboration by Cuban journalists

HAVANA TIMES – On August 12, 2015, at two in the afternoon, Paloma López called the ambulance that would take her to Ramón González Coro, an OB-GYN hospital in Havana. Early that morning, she decided to start her labor at home, as she had heard about women being ill-treated at the hospital.

When she arrived, she was six centimeters dilated but her water had not broken. “They took me to the gurney to monitor me, they lifted me and took me to a strange room. Then, without any warning, (the doctor) took out a pointy object, and bam! She stuck it in me, and it hurt. I screamed, ‘what is that!’, and it was to break my water.”

The obstetrician threw all her weight on Paloma’s stomach and used her forearm to press on the uterus to push the baby down. Paloma was startled and struck away the doctor’s hand. As she was leaning on her with her feet practically up in the air, the doctor fell to the floor.

“Look at this bitch, she doesn’t want to be helped! She’s going to kill the baby,” Paloma recalls the doctor shouting.

“Doctor, don’t say that! You have to ask me for permission.”

“No, you don’t have a clue.”

The physician tried to apply the maneuver several more times. Paloma reacted in the same way and continued to push her off. Moments later, while trying to overcome the pain, she finally allowed the obstetrician to climb onto her stomach. “They pulled me. I felt the tearing of my baby girl, how they pulled her out,” she says. “Now I know that it was premature, that it wasn’t an organic birth. And I got a huge tear from the baby down there.”

A problem in Cuba and around the globe

Over the last two years, an increasing number of Cuban mothers have shared their childbirth experiences on social media platforms and independent news outlets. Their stories have unleashed an obstetric #MeToo on the island.

Some mothers report feeling verbally or psychologically mistreated. Others said they were denied information about what was happening to them or were never asked for consent to perform harsh interventions. Many described their childbirth as a traumatic event in which they were treated as if they had no autonomy and felt that their well-being was irrelevant.

For some, the problem was that they suffered excessive medicalization or aggressive practices. One of these practices is known as the Kristeller maneuver, which involves applying manual pressure on the ribs and has been questioned by the WHO since 1996. Another common procedure is called an episiotomy. It is performed by making an incision in the perineum, a tissue located between the vagina and the anus, to facilitate childbirth. This is often performed without consent and/or when it is not required.

Other patients said they felt neglected or ignored.

Their testimonies have helped shed light on a problem that happens in most countries, but which had remained especially invisible and naturalized in Cuba: obstetric violence.

This study, Partos Rotos (Broken Births), shows this is a systemic problem in the country. Over 400 women from all provinces participated in the study. They filled out over 500 questionnaires that asked them about their births. Most of the births described were performed either by C-section or vaginal delivery and took place in the last two decades.

The research is not based on a representative sample and its results have no statistical validity. However, it is a broad enough sample to provide an overview of how obstetric violence is prevalent in the country.

The interviewees describe a health system in which their requests for pain management are ignored (86%) and aggressive procedures – that are no longer systematically performed in other countries – are still common practice in Cuba. Manual dilatation or tourniquet was performed in almost 50% of the deliveries, and the Kristeller maneuver was also applied in a similar percentage. On the other hand, episiotomies were carried out in three out of four cases.

Respondents also noted that lack of consent and ill-treatment were common. Nearly half of the women voiced that medical personnel acted without seeking their consent, which violates patients’ human rights, according to the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

In addition, 41% of the mothers interviewed reported suffering verbal or psychological violence, and that medical staff ignored their requests or even accused them of putting their babies’ lives at risk.

Cuba is not the only country where these and other violent medical practices against women are still common. This is a global phenomenon that originates in sexism and a patriarchal culture that permeates health systems.

According to Eva Margarita García, a doctor in Anthropology and author of the first thesis on obstetric violence in Europe, obstetric violence is the result of gender violence and medical malpractice. She defines it as the violence that health personnel exercise on women’s bodies and their reproductive life through dehumanized treatment, medicalization abuse, and pathologizing of their physiological processes.

García believes this violence is mediated by a gender bias that infantilizes women and serves as an excuse to treat them in a degrading manner. However, this is such a socially normalized practice that it is often difficult to identify it as a problem.

In Cuba, however, certain factors make this a particularly acute problem. For instance, according to health professionals interviewed for this research, the Cuban health system is a top-down organization in which physicians have little room for reform.

They are under strong pressure to maintain certain statistical indicators, especially regarding infant mortality, and have little incentive to improve the quality of care or consider the mothers’ well-being. Moreover, in a country that is regarded as a medical powerhouse and is under authoritarian rule, the scope for recognizing and addressing the problem is narrower than in other countries.

Sexist stereotypes

In carrying out this report, we interviewed eight medical specialists, four women, and four men, who are actively participating or have previously participated in the Maternal and Infant Care Program (Programa de Atención Materno Infantil, PAMI), a program that centralizes women’s reproductive health in Cuba. All eight specialists chose to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals, such as losing their jobs or being expelled from the Ministry of Public Health (Ministerio de Salud Pública, MINSAP).

Interviews with these physicians suggest that, in Cuba, gender stereotypes that influence how women are treated during childbirth are still very much prevalent in the health care system. For example, a general practitioner with decades of experience in the country’s central region justified several practices of obstetric violence, “especially in women with delayed labor or in women who are namby-pamby or stubborn.”

There is also an inclination to see women in labor as ignorant and/or expect them to be subordinate. Informing, asking for consent, allowing them to have companions, or simply walking around during labor is seen as an obstacle for the professionals to carry out their job. As the interviewed specialists stated, these are not common practices. “Priority is given to the baby, caring for the newborn, and that the mother does not bleed, forgetting the psychosocial being,” a gynecology and obstetrics resident in Holguín explained.

Some obstetricians also believe that childbirth is always painful, so alleviating suffering is therefore not a priority. In addition, patients who request C-sections are seen as seeking “comfort” and are “forced” into vaginal delivery.

The expectation that women obey medical indications without protesting is also common among health personnel. This notion is so deeply rooted that the women themselves have begun to tell each other that it is better to “collaborate” or “behave well” – expressions that were regularly mentioned in the questionnaires – to avoid worse forms of abuse.

Sandra Heidl, a psychologist and feminist activist who gave birth in Cuba when she was 19, believes that “the product, the fetus, is the most important thing” to the Cuban public health system, and women take a backseat as the recipient of the product. Women take or are unaware of this violence because they want the best for their unborn child, and they have been told that physicians must decide for the babies’ sake,” Heidl explains.

This subordination of the patient to the physician is a feature of what is known as the Hegemonic Medical Model (HMM). Daylis García Jordá, the author of one of the few studies on obstetric violence in Cuba, considers that the HMM tends to see the patient as ignorant or the bearer of wrong ideas, while knowledge resides only within the physician. García Jordá explains that, despite the recent criticism against this model, it continues to be in full force. As a result, it gives way to a childbirth experience in which the physician matters and the patient does not.

In fact, health systems in many countries are designed to meet the physicians’ needs, according to Dr. Matthias Sachsee, a German specialist in health care quality with experience in Mexico, and Thaís Brandao, a Brazilian researcher in sexual and reproductive health.

Cuban medical professionals acknowledged that certain violent practices are performed due to the physicians’ convenience, such as the indiscriminate use of episiotomy. “It’s the easy way for the specialists to perform the delivery, to do it quickly because they just want to get it over with,” said a Gynecology and Obstetrics in Holguin.

Other common practices such as prohibiting pregnant women from walking or having company, performing enemas, or denying them pain medication are also related to the needs of the system or the physician’s preferences, without consideration for women’s needs and suffering.

For all these reasons, researcher Brandao says obstetric violence has “institutional roots” and its main cause is the system’s unwillingness to address the problem. In her opinion, obstetric violence does not stem from a lack of resources. “You can promote healthy, non-violent births even without any resources, because (as a government or system) you understand that this is what’s important,” states Brandao.

A unique birth

Since 1975, almost 100% of births in Cuba take place in public hospitals. Unlike pregnant women in other countries, Cuban women have no say in where or how they give birth. They must give birth in the only existing system controlled by the Minsap. Thus, Minsap’s rules, priorities, and shortcomings broadly shape the experience of giving birth on the island.

That institution has shown that its main objective is to keep certain indicators low, especially infant mortality: the number of children who die during or shortly after childbirth. This is the rate that the authorities proudly present every year to showcase the success of their childbirth care system. “It is the best-kept statistic in the ministry,” assured one of the interviewed physicians.

“In Cuba, the system is structured in a way that responds more to numerical parameters and works in response to the professionals’ needs or those of Public Health as an entity when bringing a new life into this world, and not of the women and their families,” specifies academic García Jordá in her study.

The interviewed professionals agreed that the Minsap pressures them to deliver excellent statistics and comply with strict protocols, which discourages them from introducing changes or acting according to their medical judgment. It is also common for them to have to meet quotas, for example, on the maximum number of C-sections they can perform.

Many physicians condemn the pressure they are subjected to. Some feel the inflexibility of the protocols makes them mere executors of policies designed by bureaucrats who don’t know the reality in which they work.

“It is unacceptable that a program involving human management is based on meeting indexes and parameters. Physicians cannot be thinking about numbers, figures, or emulations while caring for a patient’s life. So, you work under a lot of pressure”, states a retired obstetrician who worked in the field for over 20 years.

A recently graduated physician agrees. “For me, (OB-GYN) is one of the specialties where you have to be most careful because heads are cut off at any moment for any reason.”

From the authorities’ perspective, the system works because they achieve the statistics they aim for. Fewer mothers and newborns die in Cuba than in most countries in the region, which allows the government to boast about its system. The infant mortality rate is very similar to the rates presented in countries such as the United States. In addition, maternal mortality, although much higher than in the countries in the Northern Hemisphere, is among the lowest in Latin America.

However, no statistics are collected on obstetric violence or the absence of humanized childbirth. Despite the abundance of Minsap protocols, the professionals interviewed agreed that the principles of humanized childbirth, which some countries are now starting to apply, are little known in Cuba.

“If you refer to the international bibliography, you learn about it, but the practical course does not mention it. It’s not a topic that’s even discussed,” says a gynecology and obstetrics resident from Holguín.

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) established a series of recommendations for labor. The first element it recognizes is that childbirth cannot be subject to strict protocols, such as those applied in Cuba. Instead, care should focus on the woman’s state and her baby’s, “their wishes and preferences, and respect for their dignity and autonomy.”

WHO recommends encouraging pregnant women to move around and give birth in an upright position. It also suggests allowing them to be accompanied, eating or drinking during labor, not separating babies from mothers right after birth, not applying techniques that artificially speed up natural processes, limiting vaginal touches to once every four hours, and performing episiotomies only if strictly necessary.

These recommendations not only respect women’s rights but also yield positive results from a medical standpoint. Multiple studies have shown that the more comfortable and accompanied pregnant women feel, the greater the probability that their vaginal delivery will be successful and, in turn, aggressive techniques will be required to a lesser extent.

However, questionnaires and interviews with professionals in Cuba show that these recommendations are blatantly disregarded in the country.

Not caring nor humane

Many women described giving birth in an environment that lacked empathy, warmth, or humane treatment. Others directly reported being mistreated, coerced, and verbally abused. Minsap professionals deprived them of the experience they wanted to have when their children came into the world. This contributed to the birth becoming a source of trauma.

Many interviewees stated that they experienced psychological sequelae after their birth. In 30% of deliveries, women were afraid of getting pregnant again or reported having repetitive images of particular moments when giving birth. In one of every four deliveries, women experienced mood swings, difficulty sleeping, or fear of confronting the health care system.

In addition, in 14% of childbirths, women stated they suffered from postpartum depression.

“You will rarely see (these sequelae) reflected as a diagnosis in the medical records,” explains one of the professionals. “These patients are seldom referred to mental health services for treatment, which ends up affecting the physical health and quality of life of the patients and their families,” they added.

The verbal or psychological violence, the lack of empathy, or the feeling of neglect described by the women in the questionnaires have deep causes related to the misogynistic culture and the Hegemonic Medical Model. The verticality of the Cuban health system only aggravates this context, according to the consulted physicians.

Several professionals admitted that they end up passing on the pressures and shortcomings they experience to the women they are treating. This issue can be expected to intensify as the country’s medical services have deteriorated due to a lack of personnel and resources.

Currently, medical personnel in Cuba earn between 190 and 320 USD per month, at the official exchange rate. To survive, some of them accept gifts or cash from patients and usually reserve the best care and the few materials available for their treatments.

“Obstetrics and gynecology are among the specialties that most rely on this informal exchange. If you don’t have your doctor and you ‘don’t go through the gutter’, as they say, you’re screwed,” a recently graduated doctor said from her own experience becoming a mother.

Despite the profusion of healthcare professionals in the country, interviewees described increasingly intense work schedules and shifts due to staff shortages. After shifts of three or four consecutive days on call, it is common for PAMI staff to have to work in health centers or make home visits.

At the same time, the demands to meet statistical targets show no signs of slowing down. “We have to produce results at the same level as countries that have services with all the proper conditions,” in the words of a specialist quoted in Lareisy Borges Damas’ thesis. Borges Damas is a doctor in nursing who has researched models of humanized childbirth.

Several professionals claimed to have lost motivation working with this framework, which negatively affects the quality of the care they provide.

As a gynecology and obstetrics resident from Holguín said, “Nobody wants to work here, so they let this violence happen as long as it doesn’t affect the statistics. There can be ill-treatment as long as the pregnant woman and the baby do not die. That’s more or less how it works.”

Read more from Cuba here on Havana Times

https://havanatimes.org/features/how-cubas-authoritarian-system-enables-obstetric-violence/