Reuters reported on October 30th that "wealthy nations grouped together in the Paris Club of creditors have waived Cuba’s annual payment for restructured debt but plan to impose a penalty." The article then makes the claim that "this year marks the first time Cuba has missed the entire payment due by Oct. 31 since the restructuring agreement was signed in 2015, though it fell short of full payment last year as well." Although accurate, it leaves out the prior decades that the Castro regime played the role of a dead beat whether or not economic conditions were good or ill for Havana.

The 2015 restructuring and forgiveness of debt with the Castro dictatorship, a byproduct of the detente with President Barack Obama, is providing a lifeline to the Castro regime. This is a regime that Wall Street Journal columnist Mary O'Grady observed in 2014 that "since 1959, Castro Inc. has racked up unpaid foreign debt and other claims totaling nearly $75 billion—including $35 billion owed to the Paris Club. Cuba is one of the world's most notorious deadbeats, and the Cuban economy is moribund."

In 2002 the former Executive Director of the Center for a Free Cuba, Frank Calzon, offered an assessment of U.S. economic sanctions, "say what you will about the U.S. embargo, but one of its best-kept secrets is that it has saved U.S. taxpayers millions. Because of the embargo, American banks aren't among the consortium of creditors (among them Spanish, French, Canadian banks) known as ''The Paris Club.'' A consortium that has been waiting for years to be paid what's owed."

Mr. Calzon gave a conservative assessment when he claimed that U.S. taxpayers had saved millions in bailouts. In reality, the embargo has probably saved American taxpayers hundreds of millions over the years. Consider that the above mentioned Paris Club in 2015 forgave $8.5 billion of $11.1 billion debt that the Castro regime owed. And Havana, even before COVID-19, was failing to meet its remaining obligations on its debts.

These patterns stretch back over the entire history of the Castro regime, and the leadership, despite claims in the press has not changed, and this is due to ideology. Scott B. MacDonald writing in Global Americans on November 2nd observed that "despite the revolution coming to power in 1959, Cuba has remained considerably dependent on external props to maintain a generally inefficient command economy, dominated by large state-owned companies backed by the Communist Party’s inner court and the military." The rest of the article is worth a read, but MacDonald errs when he asserts Cuba "is headed by Miguel Díaz-Canal, the first non-Castro family member to preside over the country." This is wrong on two counts.

Although General Raul Castro handed over the office of the presidency to his hand picked successor Miguel Díaz-Canel on April 19, 2018. Havana used this to give the false impression that there was a transition in Cuba. The reality is that General Castro remains head of the Cuban Communist Party and in control of the military, and in the Cuban Constitution that makes him the maximum authority.

General Alberto Rodriguez Lopez-Callejas, Raul's former son-in-law, runs the Cuban economy. Raul Castro's son, Colonel Alexandro Castro, who negotiated the normalization of relations with the Obama Administration, is an intelligence officer with close ties to the secret police. Both are key posts for running the country, and are directly tied to the Castro family and General Castro.

Osvaldo Dorticos, was another president not named Castro in Cuba following the consolidation of communism under the Castro brothers in 1959. Diaz-Canel, like Osvaldo Dorticos who was president of Cuba from 1959 to 1976, over the past two and a half years has done the bidding of the Castros.The succession was not to make Miguel Díaz-Canel the new dictator but to maintain the Castro dynasty in power. Raul Castro and the Castro family continue to preside over the country.

This is also why patterns of repression continue to remain similar. The Christian Post reported on November 2nd that in the city of Santiago de Cuba regime officials "demolished a church that has long been a target of the communist regime and arrested a pastor who streamed the demolition live on social media, a human rights group has reported."

Millions of taxpayers around the world have bailed out the Castro dictatorship, and have subsidized repression. None of them are Americans, thanks to the U.S. Embargo on the Castro regime.

Reuters, October 30, 20201:22 PM

Exclusive: Wealthy creditors give Cuba a pass, but will impose penalties

By Marc Frank

HAVANA (Reuters) - Wealthy nations grouped together in the Paris Club of creditors have waived Cuba’s annual payment for restructured debt but plan to impose a penalty

This year marks the first time Cuba has missed the entire payment due by Oct. 31 since the restructuring agreement was signed in 2015, though it fell short of full payment last year as well.

The accord, signed in tandem with the U.S. detente under former President Barack Obama, is seen as a historic effort by all parties to begin to bring Cuba back into the international financial system and has survived efforts by the administration of President Donald Trump to torpedo it.

Cuba had asked earlier this year for a two-year moratorium and the waiving of penalties for overdue payments due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The Caribbean nation’s tourism sector was closed most of the year, export earnings declined, and fierce new U.S. sanctions are making matters worse for an economy already notorious for inefficiencies and currently suffering shortages of food, medicine and other basic goods.

The United Nations forecasts growth will decline 8% this year after averaging a 1% increase since 2016.

“We are united in our belief that the agreement should be saved and think the Cubans agree. That is why we waived payment, but not the penalties,” one diplomat said. Like others, he requested anonymity as he was not authorized to discuss the matter publicly.

Paris Club negotiations with Cuba will cover unpaid maturities and penalties, as well as the scheme of future payments, the sources said.

A spokeswoman for the Paris Club said it did not comment on such matters. The Cuban government did not respond to a request for comment.

A number of the diplomats said they were encouraged by Cuba’s recent announcement that it would devalue the peso and take other measures aimed at increasing exports and cutting imports which they saw as crucial to regaining solvency.

“Creditors, from the Paris Club to Russia and China, will be very encouraged by devaluation and other measures,” said a Western banker who follows Cuba closely and also requested anonymity.

Another of the diplomats with knowledge of the Paris Club situation, said - in reference to the governments’ chief debt negotiator Recardo Cabrisas - “Mr. Cabrisas needs to come talk to us.”

Cabrisas was in Russia a few months ago where restructured Soviet-era debt, new debt and economic plans were discussed and where he said Cuba was having problems meeting those obligations as well.

The 2015 Paris Club agreement, seen by Reuters, forgave $8.5 billion of $11.1 billion, representing debt Cuba defaulted on in 1986, plus charges. Repayment of the remaining debt in annual installments was backloaded through 2033 and some of that money was allocated to funds for investments in Cuba.

Under the agreement interest was forgiven through 2020, and after that is just 1.5% of the total debt still due.

The agreement states if Cuba does not meet an annual payment schedule in full within three months of the Oct. 31 deadline, it will be charged 9% late interest for that portion in arrears.

Cuba owed an estimated $85 million this year.

Cuba last reported foreign debt of $18.2 billion in 2016, and experts believe it has risen significantly since then. The country is not a member of the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank.

“Faced with the pandemic, almost all governments are taking their debt levels to record highs, and Cuba is no exception,” said Pavel Vidal, a former Cuban central bank economist who teaches at Colombia’s Universidad Javeriana Cali.

“The fiscal deficit has grown and so have the trade imbalances. Although there is no data to know the magnitudes.”

The Cuba group of the 19-member Paris Club comprises Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Britain, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cuba-economy-debt-exclusive-idUSKBN27F2N3

Christian Post, November 2, 2020

Cuban authorities destroy church, arrest pastor who filmed demolition

By Anugrah Kumar, Christian Post Contributor

Worshipers attend the inaugural mass of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Catholic Church in Sandino, Cuba on Jan. 26, 2019. | PHOTO: DIOCESE OF ST. PETERSBURG

Authorities in the city of Santiago de Cuba demolished a church that has long been a target of the communist regime and arrested a pastor who streamed the demolition live on social media, a human rights group has reported.

According to the London-based nonprofit Christian Solidarity Worldwide, Cuban State Security brought heavy machinery and bulldozers to the Assemblies of God Church in the Abel Santamaria neighborhood of Santiago de Cuba last Friday and destroyed the church.

CSW added that the church has been under threat since 2015 even though the denomination is one of the largest religious groups in Cuba and is legally recognized by the government.

Pastor Alain Toledano who lives in the same neighborhood and pastors another church recorded the government attack on the church and broadcast it on Facebook Live through his mobile phone.

However, he dropped the phone on the ground as he was approached by men wearing plainclothes. As the video feed was cut, the sound of bulldozers could be heard as members of the church sang in the background.

Cuban police then took Toledano, a leader of the unregistered denomination the Apostolic Movement, to the Motorizada Police Station. According to CSW's report Friday, he is being kept incommunicado.

Cuban authorities have claimed that the demolition was for the construction of train tracks on the site, but CSW sources said the church was the only building in the neighborhood that was destroyed.

https://www.christianpost.com/news/cuban-authorities-destroy-church-arrest-pastor.html

Global Americans, November 2, 2020

Cuba’s Sagging Economy, Regime Change, and U.S. Policy

By Scott B. MacDonald / November 2, 2020

The Cuban economy is in a bad state. Over the past three years it has been hit hard by the U.S. embargo of Venezuela (which undercuts Caracas’ ability to provide badly needed external support), the Trump administration’s imposition of economic sanctions on Cuba itself, and the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the tourist industry throughout most of 2020. The economy is expected to contract by six percent this year, with considerable uncertainty hanging over 2021. Add to this mix the U.S. elections; if Democratic challenger Joe Biden is elected there could be a reset in relations, which could help the tourist sector but see greater action on human rights, while a second term of Republican Donald Trump could bring an even greater tightening of U.S. policies with the end-game being regime change in Havana. Cuba is likely to be high on the U.S. foreign policy agenda for whoever sits in the White House in January 2021.

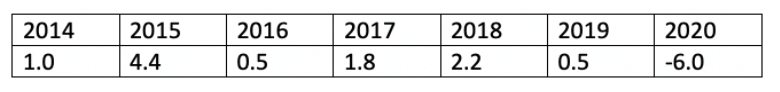

Cuba – Real GDP Growth Rate %

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

A Sagging Economy

The Cuban economy’s performance throughout the last decade has been disappointing on many fronts, putting the island-state behind much of Latin America and the Caribbean. Despite the revolution coming to power in 1959, Cuba has remained considerably dependent on external props to maintain a generally inefficient command economy, dominated by large state-owned companies backed by the Communist Party’s inner court and the military. A convoluted foreign exchange system only worsens matters. Although a private sector exists, it has only been allowed out of necessity during periods of extreme economic stress, such as the Special Period in the 1990s following the collapse of the island’s main source of foreign aid, the Soviet Union.

In 2020 most Cubans have undergone more than one period of shortages of goods, including chicken, eggs, rice and other staples. This last round of long lines and bare shelves gave rise to The Economist magazine calling Cuba, “Queueba”. A country that was once a major agricultural powerhouse, Cuba imports close to two-thirds of its food at an annual cost of USD$2 billion. At the same time, the economy’s main sources of foreign exchange revenue are professional services— driven by the export of medical professionals, tourism, and remittances. Although these sectors earn valuable currency for the country, they do not cover the trade balance deficit, meet local demands for many products such as food, or allow Cuba to address its infrastructure needs.

Cuba’s fundamental problem is that the Revolution has been largely financed by first the Russians and then the Venezuelans as well as through the many sacrifices of the Cuban people. With the increasingly troubled nature of Venezuelan assistance after 2014, the hope for the Cuban economy was that the normalization of relations with the United States would bring in a wave of U.S. tourists. Indeed, following President Barack Obama’s 2015 visit to the island tourism increased considerably. According to economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago, gross tourism revenue (without subtracting the value of imports) peaked at USD$3.2 billion in 2018.

Hopes of U.S. tourism bailing out the Cuban Revolution, however, ended with the Trump presidency in 2017. Strongly influenced by the anti-Castro Cuban-American community, the Trump administration labeled Havana as part of the “Troika of Tyranny”, which also included leftwing authoritarian governments in Venezuela and Nicaragua. The Trump administration’s sanctions against Caracas dovetailed nicely with putting Cuba under pressure, in particular, making it more difficult to send Venezuelan oil to the Caribbean island.

The Trump administration’s restrictions on U.S. tourism (such as the suspension of cruises and prohibitions from staying in government-run hotels) to Cuba also hurt: in 2019, Cuba received 9.3 percent fewer tourists than in 2018; the 2019 target of five million tourists was unfulfilled by 15 percent. The Trump administration took other measures, such as stopping U.S. travelers from bringing home Cuban cigars and rum and making it more difficult to send remittances to Cuba—the country’s second highest source of hard currency. Moreover, in a move to scare foreign investors away from Cuba, President Trump refused to sign a waiver under the 1996 Helms-Burton Act which would disallow U.S. citizens the right to sue mostly European companies that operate out of hotels, tobacco factories, distilleries and other properties that Cuba nationalized. Previous U.S. presidents had waived this part of the Helms-Burton Act to avoid complications with European allies.

Adding to the list of problems in 2019, professional services exports were hit hard by changes in the governments of Bolivia, Brazil, and Ecuador, which ended their use of Cuban doctors and technicians. These led to an estimated annual loss of around USD$1 billion in revenue although some of that loss could be clawed back by the end of 2020 as Cuban medical teams were in high demand during the pandemic.

It is in this context that Cuba was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. This resulted in a lengthy shutdown of the country, including its tourist sector. Cuba has done a relatively good job of containment. According to the World Health Organization, Cuba has had around 6,700 confirmed cases and 128 deaths due to COVID-19, compared to the Dominican Republic’s 125,008 confirmed cases and 2,226 deaths and Venezuela’s 90,100 confirmed cases and close to 800 deaths. Hopes for a gradual reopening of the island’s tourist trade now hinge on the security situation brought about by the second wave of the pandemic in North America and Europe.

Are China and Russia willing to pay for Cuba’s communism?

Cuba’s options for a new external patron are not inspiring. The Maduro government in Venezuela is struggling to remain in power and its oil industry is deeply troubled. That leaves China and Russia.

Although China has assumed a significant role in the Cuban economy through trade and investment and the forgiveness of USD$10 billion in debt, it has not demonstrated an appetite to bankroll Cuba’s dysfunctional system. President Xi Jinping and other high-ranking Chinese officials stopping off in Havana for a photo opportunity is one thing; it is another to sink several billion dollars into an economy which lacks key natural resources and whose leadership refuses to take Beijing’s advice to mix market economics with single-party Leninist rule. Additionally, China’s Venezuelan experience did not leave Beijing hungry for sinking large sums of money into another badly managed economy.

Russia has demonstrated a renewed interest in Cuba, but has balked at assuming its once formidable role of maintaining Fidel Castro’s revolutionary show. Russia is willing to offer credit-for-arms sales, project development for rail and power utilities, debt-forgiveness in writing off USD$32 billion in 2014, and visits by the Russian Navy and high-ranking government officials. China and Russia’s involvement in Cuba has geopolitical value in poking at U.S. security concerns, but Cuba’s ruling class have parked their country in an unattractive developmental cul-de-sac that has a large price tag attached; Beijing appears to have little interest and Russia cannot afford it.

The U.S. Elections

Another major factor hanging over the Cuban economy is the U.S. election. In a rally in Florida in late September 2020, President Trump stated, “I canceled the Obama-Biden sellout to the Castro regime.” Over the past four years U.S. policy has hardened considerably; another four years of a Trump administration would probably see greater efforts to squeeze the Communist regime, hoping to spark some type of regime change. This policy would also be closely linked to ongoing pressure on the Maduro regime in Venezuela, with the view that if one dictatorship is felled, the other will follow. Decades of a U.S. economic embargo dating back to the early 1960s failed to bring down the Castro regime; it remains questionable that four more years will provide a different outcome.

A Biden victory would probably lead to a rapprochement between Havana and Washington. It appears that a broader Latin American and Caribbean policy would be marked by a repudiation of the Trump administration’s hardball, new Cold War approach and driven by more of a sense of mutual respect and shared responsibility. It would probably benefit Cuba in two ways; there is a strong chance that some of the economic sanctions introduced by the Trump administration would be rolled back, allowing a more normal economic relationship—which in Cuba means tourism—and a softer approach to negotiating change in Venezuela stands a good chance of the Maduro government remaining in power longer and perhaps being able to maintain a flow of oil to its Caribbean ally. At the same time, a Biden administration might be able to extract more out of the Cuban government after having experienced four challenging years of U.S. measures. Timing is an important factor in diplomacy.

Looking Ahead

Despite Cuba’s poor economic outlook, there is hope. Cuba’s educational system has produced a class of medical professionals, who remain important to generating foreign exchange reserves and could provide a foundation for a broader regional medical hub. At the same time, the country’s entrepreneurs, called cuentapropistas, have since their emergence in the 1990s survived inconsistent and often hostile government policies. And they have been hit hard by a tightening of U.S. sanctions and the COVID-19 pandemic, which hurt tourism and related businesses upon which they depend. A loosening of U.S. economic measures, along with headway on COVID-19, would probably help revitalize private sector activity.

Part of the solution to Cuba’s economy resides in unlocking more of the private sector. Much will have to change for the Cuban private sector to rebound and eventually assume a greater role in the country’s direction. One badly needed reform would be to allow the cuentapropistas to incorporate. Indeed, the Cuban private sector has lobbied the government since 2007 for the right to incorporate, which would make it easier for them to sign contracts and conduct business with banks. The government has done little on this front, freezing the private sector out of long-term credit, which is essential for any sustained expansion.

Cuba has entered the 2020s much in the same fashion as it did in the 1990s; the world is a more uncertain place, its main economic backer is riven by a major economic collapse, and its relations with its northern neighbor are tense. But there are differences. Fidel Castro is dead and his brother Raúl is 89. The country is headed by Miguel Díaz-Canal, the first non-Castro family member to preside over the country. Although Cuba is still a police state, it is more open to the outside world through the internet and travel. Cubans have a greater understanding of the world around them than before. The pandemic has probably reinforced some of the closed nature of the polity in the short-term, but Cuba desperately needs to open up for the economy to work. If not, prospects for finding another willing donor to a failing economic experiment are going to be hard to find in a post-COVID world.

https://theglobalamericans.org/2020/11/cubas-sagging-economy-regime-change-and-u-s-policy/