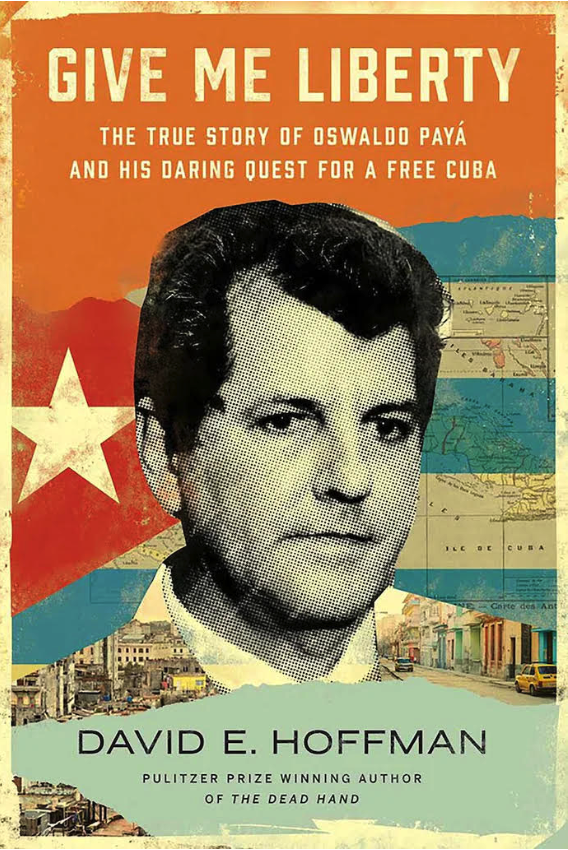

Today in The Washington Post, Contributing Editor David E. Hoffman wrote an essay, adapted from his upcoming biography of Oswaldo Payá, “Give Me Liberty,” that will be released on June 21, 2022 by Simon & Schuster, on how Cuban activist Oswaldo Payá, together with the Christian Liberation Movement that he co-founded in 1988, nonviolently and openly challenged Fidel Castro’s dictatorship, and paid for it with his life on July 22, 2012. Hoffman writes:

“Oswaldo Payá fought long and hard for democracy and respect for basic human rights. His dreams were not achieved in his lifetime; the Castro dictatorship remains entrenched. But an important legacy of Oswaldo’s quest was that gradually, painstakingly, despite the obstacles, Cubans began to raise their voices against despotism. And on one sultry summer afternoon, they became the protagonists of their own history. On July 11, 2021, a crowd gathered in San Antonio de los Baños, a small town southwest of Havana. Through their pandemic face masks, they chanted “¡Patria y Vida!,” homeland and life, the title of a hugely popular protest song that had become an anthem of discontent, a play on Fidel’s old war cry of “patria o muerte,” homeland or death… A Facebook video of the protest went viral, sparking the largest spontaneous anti-government demonstration since Fidel took power in 1959…”

He concludes on an optimistically realistic note.

“A totalitarian state does not simply flutter and faint. The Cuban regime still commands an army and vast security forces; it controls the airwaves, the border and the economy, and it monopolizes all politics. But Oswaldo Payá showed — and the events of July 11, 2021, proved again — that no state, no matter how dictatorial, can imprison an idea forever. The quest for liberty runs free.”

There are four important documentaries where you can hear the voice of Oswaldo Payá. Two are Czech based productions: Voces de la Isla de la Libertad (2000), La Primavera de Cuba [The Cuban Spring] (2003), one is U.S. based: Dissident: Oswaldo Payá and the Varela Project, and one is produced by the Cuban diaspora: The truth about the murder of Oswaldo Payá and Harold Cepero (2022).

The Christian Liberation Movement (MCL) continues both in Cuba, and in the diaspora to carry on the struggle for a free Cuba. MCL is part of a network of political parties, the Christian Democrat Organization of America (ODCA) where they joined with two other Cuban organizations, the Cuban Democratic Directorate, and the Christian Democratic Party of Cuba agreed on a resolution that advocates for isolating the Cuban dictatorship diplomatically.

"The ODCA newly recognizes and supports the 11 concrete actions of the Solidarity Campaign for the freedom of Cubans, an initiative promoted by the Christian Liberation Movement, where the governments of the region and the rest of the democratic world are asked for their support in this campaign of economic, financial and political isolation of the Cuban regime, while providing aid to the Cuban population through humanitarian channels."

There is an important conversation underway on the ethical questions surrounding Canadians going on holiday to Cuba. Representatives of the Assembly of the Cuban Resistance are in Canada visiting institutions that have relations with the Cuban government, and challenging the status quo. Two opinion pieces, one in the National Post, and another in the Toronto Star call attention to how tourism from Canada contributes to the suffering of Cubans on the island, and benefits their oppressors.

Rene Bolio, Orlando Gutierrez, and Luis Zuniga protesting Canadian tourism in Toronto.

Father Raymond J. de Souza, in his opinion piece "The ethics of vacationing in Cuba" published in the National Post exposed the ongoing "functional apartheid" in Cuba and the dictatorship's repressive nature.

"Older readers will recall the opprobrium that was heaped upon the Sun City resort in South Africa. In 1985, Little Steven of the E Street Band assembled a collection of musical superstars to record “I Ain’t Gonna Play Sun City.” The resort was a world-class destination, but the artists argued that to play Sun City was to endorse the apartheid regime and to enrich those it empowered. Are the sunny beaches of Cuba any different? There is a functional apartheid at work, not divided by race but by dollars. Until about 10 years ago, local Cubans were banned from frequenting the resorts as customers. Now, they can, but can’t afford it and are harassed if they do. The resorts are for foreigners. The regime desires their hard currency and the resorts are luxury camps designed to hide the reality of Cuba." ... "Cuba is not the world’s most dangerous regime, but it is the most dangerous regime for the Cuban people. It is also the leading protagonist in exporting repression to Venezuela and Nicaragua, and its malign influence can be found in Bolivia, Peru and elsewhere. And simply not going there on vacation takes literally no effort at all."

Dr. Orlando Gutierrez Boronat, a member of the Assembly of the Cuban Resistance, in his June 15, 2022 opinion piece, "Canadians care for Cuba, but in a careless way" in the Toronto Star outlined how tourism underwrites the repressive apparatus in Cuba.

In Cuba, more than 70 per cent of the hotels and all of the economy are controlled by the government. Research reveals that, for every dollar expended into the Cuban economy, 80 cents find its way directly into the coffers of the military. This is the same group that sentenced more than 400 demonstrators last July with jail terms of up to 30 years after a peaceful protest involving tens of thousands of ordinary Cubans who called for greater freedoms.

Lastly, in the Voice of OC Norberto Santana's article "Santana: CA State Senators Applaud Cuban Regime as Biden Blocks Diplomats From Americas Summit" published on June 13, 2022 drew the stark contract between President Joe Biden blocking Cuba’s Communist Party leaders from attending the Summit of the Americas Summit in Los Angeles, California and State Senators welcoming Alejandro Garcia del Toro, deputy chief of mission to the Embassy of Cuba in Washington D.C. into the California senate chambers with open arms.

"Biden based his decision on the regime’s abysmal human rights record and the ongoing repressive wave with thousands of kids, activists, journalists and parents jailed after they all poured into the streets of Cuba last July, calling for an end to decades of government repression. Biden also has kept Communist Cuba, which supports Russia’s war in Ukraine, on the U.S. State Department’s listing of state sponsors of terror – a distinction only applied to three other regimes: Syria, Iran and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (also known as North Korea). Yet just before the America’s Summit, California’s State Senators stood and gave Cuba’s Communist regime a rousing, standing ovation."

This embrace of the Cuban dictatorship taken by the California State Senate on May 26, 2022 while political show trials are still underway in Cuba is a moral failing of the first order, and a lack of solidarity with the Cuban people to confuse an oppressed people with their oppressor. State Senators can rectify, and join with others in calling for the expulsion of Cuba from the UN Human Rights Council, while recognizing the just and democratic demands of the Cuban people.

The Washington Post, June 16, 2022

‘Liberation is born from the soul’: Oswaldo Payá’s struggle for a free Cuba

Oswaldo Payá speaks to supporters at his Aunt Beba's house on May 14, 2002. "Liberation is born from the soul, through a stroke of lightning that God gives to Cubans," he said. "This little paper, it contains the popular will." (Jorge Uzon/AFP via Getty Images)

Contributing editor

Just before 6 a.m. on July 22, 2012, Oswaldo Payá opened the door of his house in Havana’s El Cerro neighborhood and stepped into the darkened street. He was accompanied by his young protege, Harold Cepero. Both carried overnight bags.

Oswaldo was 60 years old, with thick, wavy hair the color of charcoal and a swirl at the peak of his forehead. He had deep rings under his eyes and worry creases sometimes rippled across his brow, but his brown eyes were soft, understanding and patient. He often dressed casually, in jeans and a short-sleeved checkered shirt, the collar open wide, the buttons askew. By day, he was an engineer who specialized in medical electronics, troubleshooting lifesaving equipment at Havana hospitals. But his great passion was to change Cuba, to unleash a society of free people with unfettered rights to speak and act as they wished. He called it liberation.

He and Cepero walked past slumbering households as dogs and roosters milled about behind gates and fences. Oswaldo looked warily for cars in the shadows. Over many years, Fidel Castro’s state security had stationed surveillance vehicles in a nearby park and had paid residents in neighboring houses to inform on him. Oswaldo hoped the darkness would cover their departure, giving them a head start on a dangerous mission.

Oswaldo was going to Santiago de Cuba, 540 miles to the east, to train young activists and organize local committees for the Movimiento Cristiano Liberación, the democracy movement he founded in 1988. He started it with friends at the parish church, where four generations of his family had anchored their Catholic faith. The movimiento had grown to more than 1,000 members across the island, a civic and political group, nondenominational but driven by the values of Christian democracy that had confronted fascism and communism in the 20th century. Oswaldo, in building the movimiento, had become a leading voice of the opposition to Castro’s dictatorship.

A blue Hyundai Accent pulled up to the curb. Oswaldo softly recited a brief prayer, then climbed into the rear seat on the driver’s side; Cepero on the passenger side.

Two foreigners rode in front. They had come to Cuba expressly to assist Oswaldo and rented the blue Hyundai to drive him around, evading state security. The driver, 26-year-old Ángel Carromero, led the Madrid youth wing of Spain’s ruling Partido Popular, or People’s Party. Next to him was Aron Modig, 27, who headed the youth organization of Sweden’s Christian Democrats in Stockholm.

Oswaldo gave Carromero directions out of Havana. As the sun rose, he talked to his visitors of memories and pent-up hopes, a lifetime of visions pursued yet never quite fulfilled.

Oswaldo recalled how he had launched the Varela Project in 1998, challenging Castro’s dictatorship with an unprecedented nationwide citizen petition for democracy. The project was named for Félix Varela, a 19th-century priest and philosopher who was Cuba’s most illustrious educator. Oswaldo explained how they had doggedly collected signatures, door to door, then surprised Fidel and state security by submitting 11,020 names to the National Assembly in 2002 and 14,384 additional signatures the following year. More than 10,000 other signatures were still hidden. Nothing like it had ever happened before in Castro’s Cuba.

But Oswaldo and his movement paid a heavy price. His activity thrust him into the crosshairs of Cuba’s Seguridad del Estado, or state security, a hardened secret police trained in the methods of East Germany’s Ministry for State Security, the Stasi. In Cuba, state security harassed and intimidated dissidents and opposition figures using wiretaps, subversion, threats, detention and fear. Oswaldo took the brunt of it for years. After the first wave of Varela Project signatures was submitted, state security arrested and imprisoned 75 activists and independent journalists. They were sentenced to long prison terms in 2003 for nothing more than collecting signatures. Oswaldo was not arrested, but he was subjected to a different torment: relentless psychological warfare, including death threats.

This is the story of one man’s struggle against totalitarian rule. Throughout Cuba’s volatile history, people have risen to demand the right to rule themselves freely. They were dreamers who dared to wish for more, whose visions were often cut short, whose pursuit of liberty was often lost and then resurrected again by a new generation. Oswaldo Payá inherited those dreams and turned them into action with the Varela Project. He knew how basic rights were trampled upon in Cuba and set out, against great odds, to do something about it.

When a U.S. diplomat visited his house on Calle Peñón in 2006, Oswaldo was insistent. “People aren’t taking seriously enough the threat that they’d liquidate me,” he said.

He confided to a friend, “I see very few chances of getting out alive.”

When Castro led a ragtag band of rebels in the Sierra Maestra mountains in the late 1950s, the bearded guerrilla promised to create a democracy to replace the brutish autocracy of Fulgencio Batista. “We are fighting for the beautiful ideal of a free, democratic, and just Cuba. We want elections, but with one condition: truly free, democratic, and impartial elections,” he pledged. His manifestos spoke of “liberty,” “democracy” and “freedom.”

Once in power, Fidel took a different path. With backing from the Soviet Union and the Stasi, he constructed a dictatorship based on an overarching ideology, a single party, a secret police, total control of mass communications, the elimination of civil society and the power of a ruthless police state. His ambitions were totalitarian, to corral all of Cuba inside his revolution; as he put it, “within the Revolution, everything; against the Revolution, nothing.”

With Fidel, everything was intensely personal. He recoiled at criticism, perceiving it as disloyalty and disloyalty as treachery. He was impatient and unforgiving. He possessed none of the skills important in a democracy, such as the ability to accept defeat or compromise, to share power or to follow rules set by others. His life had been spent fighting, with words or bullets. One of Fidel’s commanders during the guerrilla war, Huber Matos, a teacher from Manzanillo, had bravely smuggled a planeload of weapons and ammunition from Costa Rica for the rebel army. Later, after Fidel was in power, Matos told the Cuban leader he was appalled at the growing influence of communism in the revolution. Castro had him arrested and sentenced to jail for 20 years.

Oswaldo devoted a lifetime to opposing Castro’s repression. He believed the rights of every person are God-given and cannot be taken away by the state. For most of his life, those rights were stolen, tarnished and denied in Cuba. Even something as innocent as hanging a sign saying “Feliz Navidad,” or “Merry Christmas“ on the bell tower of his church was considered subversive. Defiant, Oswaldo hung the sign anyway. He never lived in a state of liberty, but liberty lived in his mind and drove his fight for it.

Oswaldo, right, with friends in El Cerro. (Ofelia Acevedo)

Oswaldo was born in 1952. As a boy, he witnessed the seizure of his father’s business as Castro’s revolution confiscated private enterprises in 1965. As a teenager, he protested the Soviet tanks’ crushing of the Prague Spring in 1968 and was sent to Castro’s forced labor camps. Later, Oswaldo demanded that Catholic Church leaders in Cuba stand up for human rights and democracy; weakened by decades of repression, they chose reconciliation rather than confrontation. When Oswaldo published a popular newsletter demanding basic rights, the archbishop of Havana insisted that he stop. He would not. By the 1990s, when the collapse of the Soviet Union plunged Cubans into economic despair, Oswaldo had become a prominent advocate of democracy and basic human rights.

Oswaldo, home from a forced labor camp in 1972. (Ofelia Acevedo)

In the early 1990s, as thousands of Cubans took to the sea in flimsy rafts to escape, Oswaldo searched for ways to mobilize people to oppose the dictatorship. He admired Solidarity leader Lech Walesa and in 1990 proposed a “national dialogue” and “roundtable” similar to what happened in Poland to end Communist rule. But he had no means of public communication — no internet, no access to radio or television or newspapers. He was met with stony silence from the government.

However, Oswaldo was aware of a long-overlooked provision of Cuba’s constitution under which citizens could initiate legislation through a petition that would require 10,000 signatures. After thinking about options for many years, Oswaldo sought to bring about change by using the system against itself. The constitution and the citizen initiative would be his tools.

The early 1990s, with Ofelia, Rosa María, Reinaldo and Oswaldito. (Ofelia Acevedo)

Oswaldo had been profoundly affected by the Tiananmen Square massacre in China. He wanted nonviolent change but understood the risk that violence could flare. “We don’t think,” he said, “that a truly liberating process involves bloodshed.”

In 1991, he began to collect signatures for a vague proposal: legislation for a referendum, a national dialogue and democratic change. On July 11, government-backed thugs ransacked his house and sprayed graffiti on the walls outside: “Payá, you worm,” “CIA agent,” and “Long live Fidel.” Oswaldo picked himself up and tried again, this time with a lengthy “transition program,” a detailed road map to democracy that ran 46 pages and nine chapters. In 1995, he joined others in forming an umbrella group of civil society, Concilio Cubano. Castro’s state security went after the leaders and shut it down.

Through trial and error, Oswaldo learned. His earlier documents were too long, he realized. He needed to simplify, to be more of a preacher with a sermon than an electrical engineer with a complicated diagram.

In July 1991, a government-backed mob attacked Oswaldo’s house, where he was collecting signatures. (Ofelia Acevedo)

His next, much simplified plan was the Varela Project. It requested that the rubber-stamp National Assembly put five basic proposals to a popular referendum: freedom of association, press and expression; amnesty for political prisoners; the rights of private enterprise; a new electoral code for genuinely free elections; and new elections after the referendum. The petition was printed on a single sheet of paper creased at the half-fold, with room for 10 signatures and addresses and identification numbers. He wanted people to shed their fear and stand up to be counted.

In January 1998, a visit by Pope John Paul II electrified the island. Spontaneous shouts of “Libertad!” filled the square when the pope celebrated a final Mass. Oswaldo and his wife, Ofelia, were there with their children — and ecstatic. Days later, Oswaldo launched the Varela Project.

It was hard at first. He was constantly under surveillance and pressure from state security. They looked for weaknesses, hoping to infiltrate meetings, recruit informers and pressure members. Oswaldo watched for infiltrators. He had to step carefully; to be shrewd, skeptical and hard-nosed. Ricardo Zuñiga, a U.S. Foreign Service officer who served in Havana and knew Oswaldo during this period, recalled that state security was a formidable adversary. “They had multiple tools to aim at you: to dissuade, to co-opt, to show up at your work, to harass your children. They weren’t going to kill you, just make your life miserable.” State security typically assigned one officer to each target of repression. In the case of Oswaldo and the movimiento, it was a fellow named “Edgar.”

Henrik Ehrenberg, a Swedish democracy activist who visited Oswaldo frequently in those years, recalled, “Every meeting was a risk. State security was sometimes one step ahead of us. They would hear he was coming somewhere and go around the day before, threatening people not to come.” Oswaldo took evasive actions, postponing meetings, warning his people so they could stay out of trouble. He met them in rooms with blinds drawn. He instructed them on how to keep state security from seizing the petitions — and how to protect the people distributing them. Collecting signatures was legal under the constitution, he reminded them, but they were also going up against Fidel. “This is for real,” Oswaldo often told small groups, soberly describing the dangers ahead.

Oswaldo noticed that a spirit of resistance was blossoming in the summer of 1999. The pope’s visit had encouraged people to act on their own. The signs of civil society were unmistakable in the rise of associations of lawyers, farmers, economists, ecologists, teachers, independent libraries, youth organizations, relatives of political prisoners, and the blind or otherwise physically disabled. They were spread out across the country, not just in Havana, and the participants were becoming more diverse — youths, women, people of color. Amid all this activity, Oswaldo needed to collect more signatures. The Varela Project had hundreds but not thousands.

A breakthrough came in late 1999. The long-splintered Cuban opposition formed a new umbrella group, Todos Unidos, or everyone united. The founding document, which Oswaldo helped draft, was a direct call to the goals of the Varela Project. “We, the Cuban people, are the protagonists of our history,” it declared. “We are the ones who must create all of these spaces where we, as free men and women, can build a better society.” Oswaldo was named spokesman, essentially the leader. Soon, members of Todos Unidos became the foot soldiers of the Varela Project. Within two years, there were 100 groups working to collect signatures. It was a rare period of cohesion and common purpose.

“In the middle of this experience,” Oswaldo recalled later, “state security stopped me one day, threatened me, and told me that if the opposition in Cuba becomes unified, I’ll be imprisoned for so many years — that Todos Unidos was based on destroying the revolution and that they wouldn’t allow it.” Oswaldo had been threatened before. Now, however, he took special measures, assisted by a clandestine network of nuns, who concealed the signed petitions in convents. The petitions were cranked out on a noisy photocopier installed in the house of Oswaldo’s Aunt Beba, near his home on Calle Peñón. Every petition had a unique serial number for tracking. Every page of 10 signatures was laboriously copied and the original stored with the nuns.

On the streets, people were surprisingly eager to sign, more so than Oswaldo had anticipated. One ardent backer, Fredesvinda Hernández, collected more than 1,000 signatures, believed to be the most gathered by any single person.

Still, state security harassed the signature collectors — threatening their jobs and warning of jail time or harm to their families. Hundreds of collectors were arrested in 2000; in December alone, 270 were detained. At one point, state security detained José Daniel Ferrer, one of the project’s leaders in Santiago de Cuba, and about a dozen others. They were beaten up by a roadside, and about 130 signatures were seized. For weeks, state security officers with microphones and recording gear shadowed every member of the movimiento who came or left from Aunt Beba’s house. But the harassment didn’t slow things down. Signatures came in by the hundreds, soon the thousands.

Then state security decided to take a different approach. The Stasi had taught Cuba’s state security a simple lesson: Rather than use brute force, arrests and violence, it was often better to subvert, manipulate and paralyze quietly from within. The Stasi had created a vast corps of unofficial informants in East Germany to infiltrate any corner of society and do the dirty work. In Cuba, state security refined these methods. They knew how to infiltrate, discredit and ruin an organization.

One of Oswaldo’s close associates was Pedro Pablo Álvarez, a union organizer who had helped ramp up signature collection by pursuing signatures in small towns outside of Havana, using his labor connections. In Beba’s house one day, Álvarez closely examined a Varela Project petition. He knew from experience that Cubans all had an 11-digit national identification number and an ID card. Each digit in the individual number had a specific meaning. A single digit indicated male or female: Men were even numbers, women were odd. He focused on a certain signature, Juana, a woman’s name. Something was wrong. Juana had a man’s number. He took the page to Oswaldo. They began to look at more petitions.

Oswaldo had a sinking feeling. Hundreds of the signatures had ID numbers that were of the opposite gender. The signatures had been falsified. “Edgar” and his colleagues in state security had infected the project. Years of hard work could be ruined. It turned out that in the rush to collect signatures, the Todos Unidos-affiliated groups skipped a verification step. The mismatches were not just errors — it was a campaign of subterfuge. The very fact of falsifications would give Fidel an excuse to dismiss the whole project with a wave of his hand.

The falsifications were Oswaldo’s worst nightmare. State security was inside his network. He launched a crash campaign to validate every signature. Oswaldo selected about 250 of the most trusted members of his movement across the island and formed verification brigades. Town by town and village by village, they rechecked all the signatures, addresses and ID numbers; every original signature was verified three times. The work was done quietly so state security would not know that its infiltration had been detected.

On the evening of May 9, 2002, Oswaldo’s team gathered at Beba’s. Cardboard boxes were piled against a wall. (They were labeled “Havana Club,” a famous brand of Cuban rum, but they contained signatures brought from the nuns’ hiding places.) Two of the boxes were covered on all sides with white paper saying “Project Varela” in English and “Proyecto Varela” in Spanish. They held some 11,020 verified signatures. In Fidel’s Cuba, it was nothing short of astonishing.

Oswaldo was excited but tense, trying to avoid giving any hints to state security that anything was afoot. He picked this moment with extreme care. If state security attacked Beba’s house, they could seize the signatures and destroy the project.

Oswaldo stood in a circle with eight close associates. Looking up at the ceiling as he spoke, he said the signatures would be submitted to the National Assembly in a few days — after former U.S. president Jimmy Carter arrived on May 12 for a week-long visit. There would be extensive international coverage of Carter’s visit, the first by a former U.S. president since Fidel took power. Fidel was unlikely to want arrests or trouble while Carter was in Cuba.

After Oswaldo spoke, he silently passed around a piece of paper. Tomorrow, it read. 10 a.m.

The next morning, the two boxes containing the signed petitions were placed in the back seat of a red 1957 Chevrolet. Oswaldo and his team headed off toward the National Assembly. Several others followed in a small Volkswagen to be the observation team, standing off to watch and report to the world in case of arrests.

The Chevy jolted out of the neighborhood, down the sloping Calle Peñón. State security was caught off guard. Officers raced to their parked cars and motorcycles, but a phalanx of foreign journalists was waiting at the National Assembly — tipped off by Oswaldo’s team — including CNN, Television Española, and reporters from Associated Press and Reuters, as well as others there to cover Carter’s upcoming visit. Two of Oswaldo’s closest associates, Regis Iglesias and Tony Díaz, each grabbed a box, and Oswaldo carried a saddlebag with a list of all who had signed, a letter addressed to the president of the National Assembly and a press statement. Regis defiantly raised his hand, with a thumb and index finger making the L for “liberation.”

On May 10, 2002, Oswaldo delivered 11,020 Varela Project signatures to the National Assembly. (Jose Goitia/AP/Shutterstock)

Looking out at the crowd, Tony could see state security officers dismounting from their motorcycles and getting out of their cars. But they were beyond the cordon of journalists, so they could never make it in time to block Oswaldo, who stepped inside the building and submitted the signatures — just as the constitution provided. Afterward, Oswaldo declared to the reporters: “A new hope is opened for all Cubans. We are asking that the people of Cuba be given a voice.”

Suddenly, Julio Ruiz Pitaluga, one of the observation team members watching at a distance, lost his composure. He had served 23 years as a political prisoner in Castro’s Cuba. Overcome with emotion, he ran up and embraced Oswaldo, Regis and Tony. “I have been waiting for this day for 42 years,” he said, his voice cracking.

Fear had ruled Cubans’ lives for decades — fear of state security, of informers on every block, of arbitrary punishment for a mere remark. The Varela Project was a stake in the heart of that fear. It was a powerful gesture, though most Cubans knew very little about it, since the Varela Project had been ignored by the state-run press. The following week, Carter, in a speech televised live at the University of Havana, with Fidel sitting directly in front of him, endorsed the petition drive. Oswaldo immediately called a news conference. “Liberation is born from the soul, through a stroke of lightning that God gives to Cubans,” he declared. He challenged Castro’s government to publish the text of the Varela Project petition. Holding it up before the television cameras, he said, “Look how short it is! They’re so afraid of it. This little paper, it contains the popular will.”

Oswaldo was awarded the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought by the European Parliament in 2002. But upon his return to Cuba, state security cracked down, arresting 75 activists and journalists. In this period, known as the “Black Spring,” Oswaldo was not imprisoned, but he was tormented by the sentences inflicted on his friends. They were released in 2010 after intervention by the Catholic Church.

A decade later, on July 22, 2012, on his way to Santiago de Cuba, still trying to rally people for democracy, Oswaldo was in the back seat of the Hyundai with Cepero, his protege, as they drove deep in the Cuban countryside.

Oswaldo’s long talk included a description of the day-to-day hardships on the island. Production of sugar and tobacco — once mainstays of the economy — had fallen below 1950s levels. For most of Cuba’s 11 million people, living conditions were dire, salaries paltry, food and goods scarce.

By then, Fidel, almost 86 years old, had relinquished power to his brother Raúl, who eased up slightly on the economy but maintained a hard line against dissent.

Several hours into their trip, Carromero, the driver, noticed a car following them. A red Lada, the Soviet-era boxy auto fashioned after the Fiat, was on their tail, though distant. The road was getting worse, and Carromero slowed. Carromero mentioned the red Lada to Oswaldo, who said, “Do not give them any reason to stop us.” Carromero asked Oswaldo whether it was normal to be followed in such a remote area. Yes, Oswaldo replied. But he urged Carromero to remain calm. His tone was reassuring. He said that state security often did this to show who was boss. They wanted everyone to live in fear.

The red Lada disappeared. Oswaldo’s car stopped twice for gas; at the second stop, they grabbed sandwiches. A boy was selling music CDs. Cepero bought two: a compilation of the Beatles, and one by a Cuban artist.

Back on the road, a hot breeze rushed through the car windows. Carromero slipped the Beatles CD in and turned up the volume. Oswaldo was particularly fond of the “Abbey Road” classic “Oh! Darling.” The music and warm air lulled Modig to sleep, while Oswaldo and Cepero sang their hearts out.

Then Carromero noticed something in the mirror. A second car was tailing them, newer than the red Lada, and it was closing in, stubbornly. Carromero saw two men in the car. Oswaldo and Cepero turned around, too. “The Communists,” Cepero said with a tone of scorn, referring to state security. The car’s license plate was blue, the color of government vehicles. Carromero asked what he should do. Oswaldo again said, Don’t give them any reason to stop us. Just keep going.

The car drew closer. Carromero could see the driver’s eyes. Then the other car seemed to leap forward. It charged at the Hyundai. Carromero lost control. Oswaldo and Cepero were killed in the crash, which has never been satisfactorily investigated.

Oswaldo Payá fought long and hard for democracy and respect for basic human rights. His dreams were not achieved in his lifetime; the Castro dictatorship remains entrenched. But an important legacy of Oswaldo’s quest was that gradually, painstakingly, despite the obstacles, Cubans began to raise their voices against despotism.

And on one sultry summer afternoon, they became the protagonists of their own history.

On July 11, 2021, a crowd gathered in San Antonio de los Baños, a small town southwest of Havana. Through their pandemic face masks, they chanted “¡Patria y Vida!,” homeland and life, the title of a hugely popular protest song that had become an anthem of discontent, a play on Fidel’s old war cry of “patria o muerte,” homeland or death. The lyrics of the new song declare, “No more lies, my people ask for freedom.” As the crowd marched, more shouts erupted: “¡Libertad! Down with dictatorship! We are not afraid!”

A Facebook video of the protest went viral, sparking the largest spontaneous anti-government demonstration since Fidel took power in 1959. Ultimately, a 100,000 or more people in 30 cities and towns expressed fury over shoddy medical care, electricity blackouts, hunger and the regime’s political straitjacket. Sudden and vast, the outpouring of discontent was authentic grass-roots anger — and almost entirely peaceful.

In response to the protests, state security sent plainclothes thugs to beat demonstrators with metal rods. One protester was killed. More than 1,300 people were detained, including teenagers. Many reported physical abuse after being arrested, including jailhouse beatings with batons. Most had done nothing more than shout “¡Libertad!”

As Oswaldo learned, change is hard. A totalitarian state does not simply flutter and faint. The Cuban regime still commands an army and vast security forces; it controls the airwaves, the border and the economy, and it monopolizes all politics. But Oswaldo Payá showed — and the events of July 11, 2021, proved again — that no state, no matter how dictatorial, can imprison an idea forever. The quest for liberty runs free.

National Post, Jun 15, 2022

Raymond J. de Souza: The ethics of vacationing in Cuba

Is it morally acceptable to vacation in the island jail known as Cuba?

If Canadians care about where their comestibles comes from, ought they care where they go on vacation, as well? The ubiquity of ethically sourced coffee, free-range chickens, dolphin-friendly tuna and pesticide-free pomegranates suggests that a great number of people realize that the decisions they make as consumers — like all free choices — are moral choices.

Is it morally acceptable to vacation in the island jail known as Cuba? Lots of Canadians do. Some 40 per cent of all tourists in Cuba are Canadians. Perhaps some are drawn by the ideological devotion of “the Cuban people who had a deep and lasting affection for ‘el Comandante,’ ” as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau gushed through his grief upon the death of Fidel Castro.

But most go to loll on the lovely Cuban beaches. For my part, I resolved years ago to never go on holiday in Cuba as long as the Castro regime was in power. It wasn’t much of a sacrifice though. I get bored on the beach by the second hour and don’t like the heat. Beach vacations at an all-inclusive resort are not really suited to an avid indoorsman who rarely takes a second drink. Yet if I was forced to go, I would go elsewhere.

Happily, Fidel is dead and Raul Castro retired last year as first secretary of the Cuban Communist party. Miguel Diaz-Canel is now president. Yet the repression did not relent — same regime, different tyrant.

Last July, long-suffering Cubans — exasperated by a lack of food and medicines, despite Castro’s supposed health-care success — massively took to the streets to demand liberty. The brutality of the regime’s response no doubt stirred up fond memories of the beloved Comandante himself. Protesters were rounded up and many were frog-marched through sham trials and sentenced to decades in prison.

I wrote recently about Latin America’s backsliding on the freedom agenda of the late 20th century. Providentially, this week, Cuban freedom activists launched a campaign to get Canadians to think about Cuban liberty before they slide down there in search of some sun. Freedom for the Cuban people is at least as important as freedom for Canadian poultry.

I was pleased to meet them this week and hear firsthand about the dynamics of tyrant-friendly tourism.

“We are convinced the timing is right for Canadians to consider the small but concrete actions they can take to help Cubans find freedom,” said Orlando Gutiérrez-Boronat, the general secretary of the Cuban Democratic Directorate. He is part of the Assembly of the Cuban Resistance, a coalition of human rights groups inside and outside Cuba that is leading the campaign UnLockCuba.org, which was launched this week in France, Spain, Italy and Canada.

“Year after year, decade after decade, the regime has lorded over our people and has done so with the financial support of individuals, business and even governments that are not aware of the realities on the island.”

The United States and the financial remittances of Cuban-Americans have the greatest impact upon Cuba, to be sure. But other factors — including Canadian tourists — have an impact, too.

“The Cuban military almost exclusively owns the resorts and hotels and are the ones who see 80 to 90 per cent of the money, not the Cuban people,” claimed Gutiérrez-Boronat.

Older readers will recall the opprobrium that was heaped upon the Sun City resort in South Africa. In 1985, Little Steven of the E Street Band assembled a collection of musical superstars to record “I Ain’t Gonna Play Sun City.” The resort was a world-class destination, but the artists argued that to play Sun City was to endorse the apartheid regime and to enrich those it empowered.

Are the sunny beaches of Cuba any different? There is a functional apartheid at work, not divided by race but by dollars. Until about 10 years ago, local Cubans were banned from frequenting the resorts as customers. Now, they can, but can’t afford it and are harassed if they do. The resorts are for foreigners. The regime desires their hard currency and the resorts are luxury camps designed to hide the reality of Cuba.

Consumer behaviour is moral behaviour. That’s not really controversial, although making judgments about what degree of co-operation with evil is involved is usually very complex. National Post columnist Kelly McParland attempted to go a year without buying anything from China, a noble venture that he learned “takes persistence, pig-headedness and a willingness to pay more than the lowest conceivable price to avoid offering financial support to what many believe is the world’s most dangerous regime.”

Cuba is not the world’s most dangerous regime, but it is the most dangerous regime for the Cuban people. It is also the leading protagonist in exporting repression to Venezuela and Nicaragua, and its malign influence can be found in Bolivia, Peru and elsewhere. And simply not going there on vacation takes literally no effort at all.

I look forward one day to a Cuban vacation, even if not for the beaches. But not yet.

National Post

https://nationalpost.com/opinion/raymond-j-de-souza-the-ethics-of-vacationing-in-cuba

Toronto Star, June 15, 2022

Canadians care for Cuba, but in a careless way

Your tourism dollars and many of your corporations are supporting tyranny, injustice, and human rights abuses in Cuba. And things are getting worse.

By Orlando Gutierrez Boronat, Contributor

Wed., June 15, 2022

Seduction is a powerful force in our world. It has always been this way. The cunning, the beautiful, but especially the strong, when ill-intentioned, lure their prey into submission through it and then use a threatening show of force and lies to keep their prey subservient and subjugated.

Bienvenidos to the world of Cuba, land of the romantic getaway, “worker’s paradise” and a country where everyone is “educated,” but among the poorest of the poor, and where misinformation is common currency.

Do Canadians know the real Cuba? Savvy as Canadians are in worldly affairs, and notwithstanding the halo around your international humanitarian aid record, it pains me to break it to you — most Canadians are careless when it comes to Cuba. Your tourism dollars, and too many of your corporations, are supporting tyranny, injustice, and human rights abuses on our island. And things are getting worse.

For more than 60 long years, Cuba has been ruled by an abusive, undemocratic, and fearful military government regime. The vast majority of Cubans have been waiting patiently for free elections, their rights to be restored, and a more effective decentralized economy that encourages entrepreneurship, creation of wealth, and innovation.

Instead, they’ve endured continual abuse and repression at the hands of the one-party socialist system that sucks away wealth, stifles innovation, and only succeeds at making everyone equally poor — with the exception of the military ruling class.

To make things worse, Cubans must endure the endless barrage of tourists who unwittingly fall into the trap set for them by the Communist Party of Cuba — the only party allowed to think and act on the island. The travellers come with cash, romanticized images of revolutionary fighters, and occasional goody bags for my people. Unbeknownst to them, the main beneficiary of their travels and good intentions is the illegitimate, criminal government that rules with an iron fist.

In Cuba, more than 70 per cent of the hotels and all of the economy are controlled by the government. Research reveals that, for every dollar expended into the Cuban economy, 80 cents find its way directly into the coffers of the military. This is the same group that sentenced more than 400 demonstrators last July with jail terms of up to 30 years after a peaceful protest involving tens of thousands of ordinary Cubans who called for greater freedoms.

In fact, over the past three years, under the cover of COVID and, more recently, war on Ukraine, the Cuban government has ratcheted up its repression. Though painful, it has galvanized groups around the world to slowly awake from their slumber to express solidarity toward the Cuban people.

In Argentina, for example, two NGOs recently set up stands with books by banned Cuban authors at the 2022 Book Fair to encourage their citizens to consider human rights issues on the island. In Spain, several political parties linked arms in public marches to call for an end to Cuban repression. Yet still many Canadians remain oblivious to the realities of life in Cuba.

In 2022, the World Bank established that the threshold for poverty in Latin America is a salary of approximately $2.15 per day or less. After decades of full socialism imposed by force and supported by ignorance or indifference from other nations, the average income of a worker in Cuba is between $20 and $25 per month. Is this a country worth supporting with your travel dollars? More apropos: is this not a situation worth denouncing and resisting?

At first glance, Canadians seem committed to human rights and freedoms, democracy, and peacekeeping. Over the years, while focusing our efforts on the United States, we’ve forgotten that Canadians play one of the biggest roles in supporting our oppressors.

I’m happy you care. Now let’s do something that can actually help our people for real and for good.

Dr. Orlando Gutierrez Boronat is a member of the Assembly of the Cuban Resistance. He was born in Havana in 1965 and lives in Miami.

Voice of OC, June 13, 2022

Santana: CA State Senators Applaud Cuban Regime as Biden Blocks Diplomats From Americas Summit

State Senate chamber. Credit: California State Capitol Museum Twitter

While President Joe Biden blocked Cuba’s Communist Party leaders from the Americas Summit on Democracy in Los Angeles last week, California Senators seemingly welcomed a top-ranking Cuban diplomat into the senate chambers with open arms.

Biden based his decision on the regime’s abysmal human rights record and the ongoing repressive wave with thousands of kids, activists, journalists and parents jailed after they all poured into the streets of Cuba last July, calling for an end to decades of government repression.

Biden also has kept Communist Cuba, which supports Russia’s war in Ukraine, on the U.S. State Department’s listing of state sponsors of terror – a distinction only applied to three other regimes: Syria, Iran and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (also known as North Korea).

Yet just before the America’s Summit, California’s State Senators stood and gave Cuba’s Communist regime a rousing, standing ovation.

Cuba’s Regime Jailed Thousands Who Hit The Streets Last July Calling For Freedom

By way of background, here’s the first sentence of the most recent Human Rights Watch report on Cuba:

“The Cuban government continues to repress dissent and deter public criticism, including through brutal abuse against massive anti-government demonstrations in July 2021. It routinely relies on long and short-term arbitrary detention to harass and intimidate critics, independent activists, artists, protesters, and others.”

You can find similar descriptions in a host of international human rights organizations’ reports on Cuba.

Yet California’s State Senate leaders called it “a distinct honor” to welcome Cuba’s Deputy Chief of Mission to the U.S. as a “very special dignitary” into the Senate chambers, an infrequent practice in years past to publicly introduce international leaders to the state’s most senior legislative leaders.

Here’s a link to see the CA State Senate legislative season where Cuba’s Deputy Mission Chief addresses Senators right at the start, about the two-minute mark.

At the start of the Senate’s May 26 session, Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins, a Democrat from San Diego, noted that she was “incredibly honored” to introduce Alejandro Garcia del Toro, deputy chief of mission to the embassy of Cuba in D.C.

Atkins noted that del Toro was being escorted to the chambers by the chair of the Senate’s Latino Caucus, Sen. Maria Elena Durazo – a fellow Democratic Senator from LA – and then proceeded to summarize his diplomatic experience as a former ambassador to the Bahamas, along with two stints in D.C. and a law degree from the University of Havana.

Atkins, who mentioned she’s traveled to Cuba twice, added that del Toro was in town to meet with local labor leaders, and that he would be attending Sacramento’s Central Labor Council’s Salute to Labor annual dinner.

Yet with all that background research, nobody bothered to mention all the Cuban kids in prison for protesting last July.

Not a word about the fact that the distinct honor they bestowed upon del Toro is a privilege that ordinary Cuban’s don’t get: Access to their own government, much less a chance to dissent.

Not a word about still being classified as a state sponsor of terror by the U. S. State Department.

A Warm, Wonderful California Welcome

Instead, Atkins and the state senate offered Cuba’s regime a “warm, wonderful California welcome,” in her own words.

Along with an open mic.

“Despite the very bad narrative that is common to hear in the U.S. media about Cuba,” Del Toro said, “we can assure you Cuba is not a threat to the U.S. Cuba is a neighbor country of the U.S.”

“One of the main goals of the Cuban government, even of the Cuban people, is to try to have a better relations, mutual and respectful relations with the U.S. and that includes of course mutual benefit relations with the State of California.”

Ironically, del Toro credited senators – comprised of opposing political parties headed into competitive elections – for “enacting laws for the people of California.”

He neglected to mention that’s a privilege the Cuban government doesn’t bestow upon its own people.

In Cuba, to have any kind of political opinion, you must be a committed Communist.

That is the only political option available to any Cuban citizen trying to improve their quality of life or the economy.

Any Cuban that doesn’t like that and gets vocal about it, faces being beaten up, jailed or forced to go into quiet exile, where of course they are expected to work hard abroad and send money back home — to help finance the military-police state.

Now, I understand the concept of engagement with closed regimes.

It’s supposed to democratize them, open their economies up.

Yet I think the historical record raises questions whether this kind of one-sided, quiet engagement just opens up limited economic opportunities for a few and hinders progress on democracy, fair labor standards or human rights for the majority.

I don’t hear about great labor standards in China, Vietnam or Cuba.

I wonder how much Northern California labor leaders really know about labor conditions inside Cuba’s hotels on the island or sugar and tobacco plantations?

I wonder if they asked?

Do they realize that just like political parties, the Cuban government controls labor unions?

I wonder if these local labor leaders are in favor of having the federal government run their unions?

Don’t forget that Cuban officials also have zero tolerance for any kind of independent media and aren’t very friendly at all toward any kind of organized religion.

The only people who can have a say inside Cuba are Communists.

Going Local

My own parents were among the many who were forced to leave Cuba in the 1960s because they were Catholics and not Communists. Thus, I was born and grew up in Southern California, granting me a unique right under the U.S. Constitution – I’d argue even a responsibility – to ask questions as a free person about government decisions.

Now, I didn’t get much information from the bureaucrats at the CA Senate Office of International Relations, which organizes these kinds of presentations, or from Atkins, the state senator that organized this public introduction.

The Senate Office on International Relations didn’t seem excited at all to talk about how this invitation went out.

Oftentimes, these offices are all about international engagement until there’s questions about human rights.

Every government in the world faces these questions.

Free people should never ignore that debate.

Californians should always ask these questions before agreeing to do business or cultural exchanges.

That’s real engagement.

Now, as always in a democracy, when stumped at the higher levels, I went local to find a voice.

I started with my local delegation of state senators from Orange County to find out what’s up.

Several California State Senators said once they began to realize who they were honoring and applauding for, a sense of unease took over.

“It was a total blindside,” said Republican State Senator Pat Bates, who represents much of South Orange County.

“I kept wondering who is this person and why we are doing this?” Bates said.

Democratic State Senator Josh Newman also was surprised by the presentation, noting that he had no idea who was being presented.

“I wasn’t aware beforehand of arrangements to have the Cuban Chief of Mission give remarks on the Senate floor on May 26th,” Newman texted back to my questions, adding, “I didn’t pose for the photograph with him, nor did I attend any reception held on his behalf following. I do appreciate that it would be a cause of concern and, for many, anger that a representative of the Cuban government appears to have received such a favorable reception and without a discussion as to the significance or symbolism of such an event.”

When asked about how the event was organized and whether human rights issues were addressed with the Cuban representative, Atkins’ office completely sidestepped specific questions and only offered a general statement.

“The Senate is proud to have welcomed representatives from around the globe. There is no question that the US-Cuba relationship is a challenging one. The US continues to press Cuba for important changes that will improve that relationship, and the Senate looks forward to when there can be more interaction between the people of California and the people of Cuba,” read Atkins’ statement.

Two Orange County Democratic state senators also ran from the debate.

State Senator Dave Min referred all questions, through a spokesperson, to the Senate Office of International Relations, which promptly punted answering questions to Atkins’ office, which took all day to send back a dry sandwich quote.

State Senator Tom Umberg, who can be clearly seen standing and applauding the Cuban diplomat in the Senate chamber video, had no comment when I reached out both through text and through an office spokeswoman.

I also tried to reach out to a host of Latino State Senators on the issue.

Despite the fact that Atkins seemed to publicly characterize the effort as led by the Latino caucus, virtually no Latino senators – like Durazo or State Sen. Anna Caballero would engage when I directed questions to both of them.

Caballero, a Northern California Democratic Senator, who introduced del Toro as the presiding officer at the start of the Senate session as a “distinct honor” said through a spokesperson, “Senator Caballero attended this meeting at the request of the PT (Pro Tem Atkins), and led no such efforts. Please reach out to their office for further information.”

State Senator Bob Archuletta, a Democrat who represents a sizable Cuban American community in Downey in the midst of his Southeast LA district, backed hosting the Cuban diplomat and offering him an open mic.

“The California state senate has a long history and tradition of welcoming delegations, diplomats and other special guests to Senate chambers,” Archuletta said through a spokesman. “This is an opportunity to share our democracy and open government with others who sometimes do not have the same opportunities. The Cuban delegation was no different. I look forward to welcoming anybody to witness our great democracy in action.”

Reactions from a Cuban American Neighborhood in Southern California

The view that Cuba’s government is just like “anybody” and “no different” draws a very different reaction when put to those who have experienced Cuba.

When I read Archuletta’s quotes to Latinos in the district with a knowledge of Cuba, the reaction was pretty much unanimous.

“Wow.”

“It shows you that’s an uneducated point of view. It shows you no thought for his residents in his district. It’s uninformed and an insult to all democracy-loving people everywhere,” said Mario Guerra, a two-time mayor of Downey who came close in 2014 to himself becoming a Republican State Senator for the district.

“It says a lot about the State of California,” he said.

“Cuba is one of the few communist governments that still exist in the world,” said Guerra, questioning Sacramento’s focus on Cuba as opposed to so many other democratic governments that could be offered a chance to introduce themselves to the state senate.

Guerra, 63, was born in Cuba in 1959 and left on one of the first Freedom Flights from Cuba. He still remembers the exact date, Dec. 21, 1965, and like many Cuban families came to Southern California, helping create vibrant neighborhoods in places like Huntington Park with his family, later moving to Downey.

He eventually became a successful insurance broker and local deacon at his Catholic Church and served as Downey Mayor from 2006 to 2014, when he ran for State Senate, losing to former State Sen. Tony Mendoza.

The former Downey mayor also took issue with Atkins’ leadership in recognizing such a regime – especially amidst an ongoing repressive wave – saying it totally ignores the Cuban American experience here in California.

He was even more taken back by Archuletta’s comments, given that many families in his district are so directly affected by human rights abuses in Cuba.

“It’s so wrong. It’s laughable for an elected official in the State of California, especially one that represents lots of Cuban Americans … I am embarrassed for him and disappointed.”

“Shame on you. Shame on your leader, Sen. Toni Atkins,” Guerra said, adding the members should take the time to educate themselves on Cuba.

Is California’s State Senate Really Interested in Hearing From the Other Side?

When asked whether there’s an ethical obligation to present another side of Cuba to the State Senate, Newman agreed saying it was a “moral obligation.”

Bates also agreed that it was “reasonable” there should be an opposing viewpoint brought to the Senate, “so we can hear the other side of what’s going on there,” she said.

A spokesperson for Archuletta said he also would likely be open to hearing from a recognized opposition voice.

Newman even got curious when I informed him that many Cuban dissidents had attended the LA summit.

Because the Biden Administration blocked Cuba’s regime from the America’s summit, for the first time ever, the voice of Cuba at the democracy summit came from people like Rosa Maria Paya.

Her father, Oswaldo, was a Cuban dissident who successfully led thousands in a signature effort inside Cuba calling for a plebiscite, under the Cuban constitution, about the future of the government.

After securing the signatures, he was killed suspiciously in a car accident in Havana in 2012.

His death has never been investigated. Rosa Maria continues to call for investigations into his death and speak out about human rights abuses in Cuba.

The 10-year anniversary of his death is on July 22.

David Hoffman, a Pulitzer Prize winning contributing editor with The Washington Post is about to release a book about Paya’s life and untimely death.

When I asked her about the message sent by the California State Senate, Rosa Maria Paya lamented the fact that these legislators handed an open mic to one of the world’s most anti-democratic regimes.

“The Cuba dictatorship applies state terrorism against our people that have been silenced for 63 years. For that reason, it is a victory for the Cuban, Venezuelan and Nicaraguan people that their dictators were rightfully left out of last week’s Summit of the Americas,” said Paya through a spokeswoman.

“However, giving a public platform in the Congress of the State of California, to the Cuban totalitarian regime is a disgrace,” she said. “Particularly when there are over 1,000 political prisoners sitting in Cuban jails, many of whom have been tortured and are serving long sentences for participating in peaceful protests last July 11th.”

Every Cuban deserves a voice, Paya said.

“Hearing from not only the opposition, but from the people of Cuba, is what is right and just. Their voices should be given at minimum the same attention as has been given by the State Congress to the propaganda of the dictatorship.”

•••