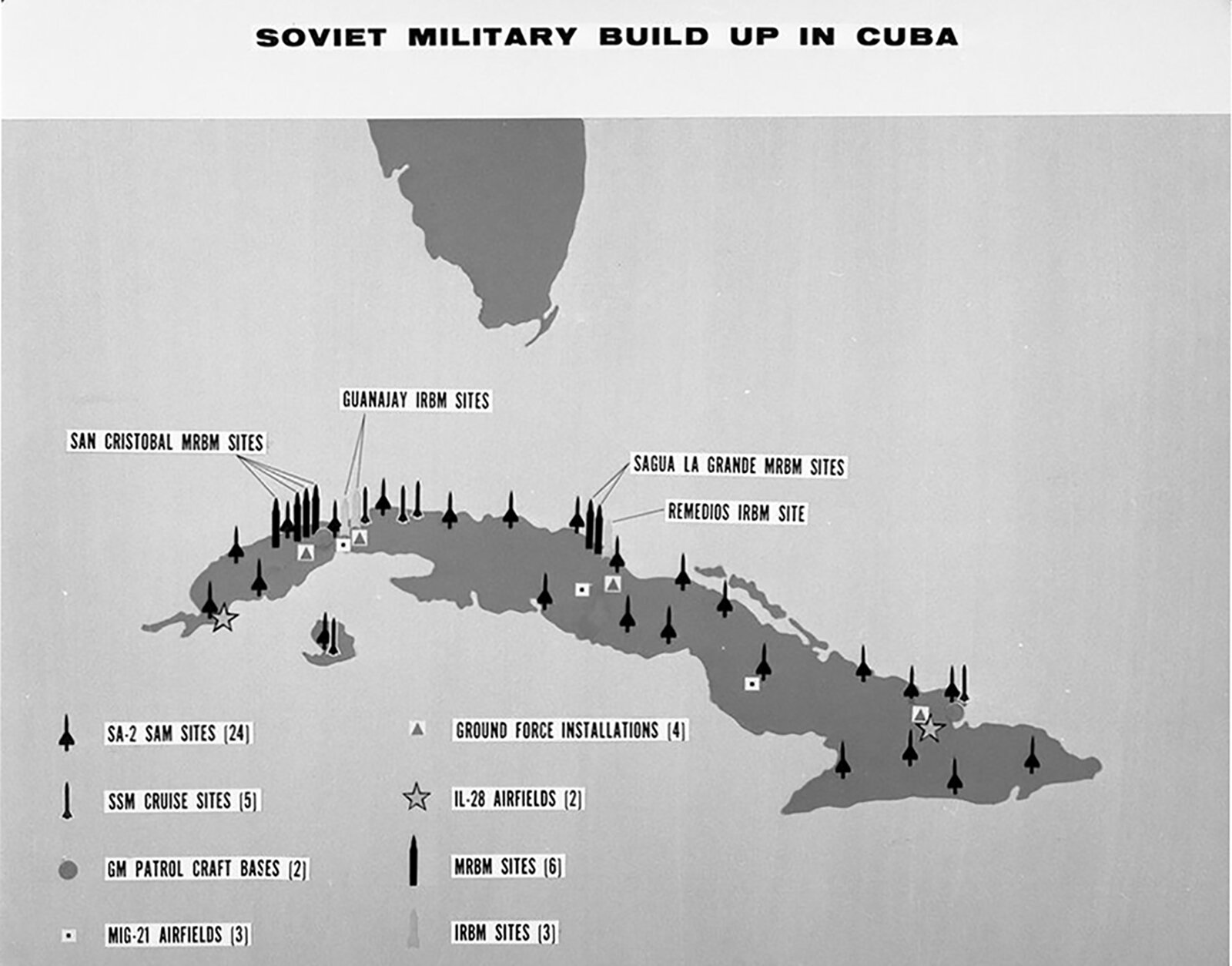

Department of Defense Cuban Missile Crisis Briefing Materials. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

The world is marking another anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the days in October 1962, when the Soviet Union introduced offensive nuclear missiles into Cuba, and the United States blockaded the island and after eleven tense days Moscow withdrew its missiles. This crisis brought the world perilously close to nuclear armageddon. Professor Jaime Suchlicki of the Cuban Studies Institute draws on this history in the important essay "What We Learned From The Cuban Missile Crisis", and concludes that this crisis was precipitated by perceptions of American weakness.

"The single most important event encouraging and accelerating Soviet involvement in Cuba was the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961. The U.S. failure to act decisively against Castro gave the Soviets illusions about U.S. determination and interest in the island. The Kremlin leaders believed that further economic and even military involvement in Cuba would not entail any danger to the Soviet Union itself and would not seriously jeopardize U.S.-Soviet relations. This view was further reinforced by President Kennedy’s apologetic attitude concerning the Bay of Pigs invasion and his generally weak performance during his summit meeting with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna in June of 1961."

Most analysts focus on the interplay in the crisis between the Soviet Union and the United States, and justifiably so, these two great powers had the stockpiles of nuclear weapons, but only touch superficially on Cuba, and its reactions during and after the crisis. This is a mistake, and one that has had dire consequences in the past, when great powers ignored the agency of small countries, such as Serbia, and the Serbian terrorist group, Black Hand, whose assassination of an Archduke unleashed a series of events that sparked World War One. Fidel Castro personally came very close on October 27, 1963 to starting World War Three.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Soviet warheads on Cuban soil would have destroyed major U.S. cities. (Bettmann / Corbis)

On October 14, 2012 the fiftieth anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis the National Archives and the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum held a forum titled "50th Anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis" during which scholar and former CIA analyst Brian Latell outlined Castro's attempts to spark a conflict while Kennedy and Khrushchev were seeking to avoid war:

"As Khrushchev and Kennedy were struggling during those last few days to resolve the crisis without resorting to war, Fidel Castro was stimulating military conflict. Castro, on the morning of October 27th -- “Black Saturday” that we keep hearing about, the worst, the most dangerous, the most tense day of the Missile Crisis -- Fidel Castro ordered all of his artillery to begin firing on American reconnaissance aircraft at dawn, at sunrise that morning of “Black Saturday.”

Fidel Castro said later on the record, “War began in those moments.” And the commander, one of the Soviet generals there with the expeditionary force, General Gribkov, said essentially the same thing. He said that, “We Soviet commanders, all the way from the generals down to the lieutenants in the Soviet force, we all agreed that conflict, military conflict, essentially began that morning.” October 27th, “Black Saturday,” Kennedy and Khrushchev are desperately trying to bring this crisis to a peaceful end, and Castro is stoking the fan of conflict.

Fidel Castro was so persuasive with his Soviet military counterparts that later that day, “Black Saturday,” the U-2 was shot down. We saw earlier in the video that the U-2 was shot down. It’s very interesting. Nikita Khrushchev believed, I think until his death, that Fidel Castro had personally ordered the shoot-down by a Soviet ground-to-air missile site, Khrushchev believed that Castro had actually somehow been responsible for it himself."

On October 27, 1962, the same day that Fidel Castro ordered artillery to fire on American reconnaissance aircraft, Khrushchev received a letter from the Cuban dictator, that historians call the Armageddon letter, in which he called for a Soviet first strike on the United States, in the event of a US invasion of Cuba.

If an aggression of the second variant occurs, and the imperialists attack Cuba with the aim of occupying it, then the danger posed by such an aggressive measure will be so immense for all humanity that the Soviet Union will in circumstances be able to allow it, or to permit the creation of conditions in which the imperialists might initiate a nuclear strike against the USSR as well.

Thankfully, Kennedy and Khrushchev reached a peaceful outcome, but the Castro regime continued to protest and was unhappy with their Soviet allies. Ernesto "Che" Guevara's essay "Tactics and strategy of the Latin American Revolution (October - November 1962)" was posthumously published by the official publication Verde Olivo on October 9, 1968, and even at this date was not only Guevara's view but the official view:

"Here is the electrifying example of a people prepared to suffer nuclear immolation so that its ashes may serve as a foundation for new societies. When an agreement was reached by which the atomic missiles were removed, without asking our people, we were not relieved or thankful for the truce; instead we denounced the move with our own voice."

In the same essay, the dead Argentine served as a mouthpiece for the Castro regime declaring: "We do assert, however, that we must follow the road of liberation even though it may cost millions of nuclear war victims."

Perceived American weakness in 1962 brought the world to the brink of nuclear armageddon. Twenty years later, during the Reagan Administration, when Fidel Castro was once again advocating for nuclear war, the Soviets quickly shut him down and did not entertain his apocalyptic plans.

The New York Times on September 21, 2009 published the article "Details Emerge of Cold War Nuclear Threat by Cuba" written by William J. Broad, the Science writer at the paper of record, revealed that Castro had continued to push for the wholesale destruction of the United State by a Soviet first strike in the 1980s.

The Pentagon study attributes the Cuba revelation to Andrian A. Danilevich, a Soviet general staff officer from 1964 to ’90 and director of the staff officers who wrote the Soviet Union’s final reference guide on strategic and nuclear planning. In the early 1980s, the study quotes him as saying that Mr. Castro “pressed hard for a tougher Soviet line against the U.S. up to and including possible nuclear strikes.” The general staff, General Danilevich continued, “had to actively disabuse him of this view by spelling out the ecological consequences for Cuba of a Soviet strike against the U.S.” That information, the general concluded, “changed Castro’s positions considerably.”

The Castro regime's conduct during the Cuban Missile Crisis was not an aberration, but a feature of the dictatorship. It is an outlaw regime. Former Florida Governor Jeb Bush and former Center for a Free Cuba executive director Frank Calzon eight years ago on October 23, 2012 writing in The Wall Street Journal warned the 2012 U.S. presidential candidates about the nature of the Castro regime observing:

"The past decades have shown that the behavior of the Castro brothers in 1962 was perfectly characteristic. Fidel Castro has never shied away from a political gamble such as deploying secret Soviet missiles and then lying about them. He assured other governments that he would never do such a thing, just as the Soviet Union's ambassador to the United States told the Kennedy administration that rumors about missiles were false. But the missiles were there, and their deployment was an effort to intimidate and blackmail America. Today, Havana's intimidation and blackmail are of a different magnitude, but there are plenty of examples."

Conventional opinion in Washington, D.C. was that normalizing relations with the Castro regime was "low hanging fruit" for the Obama Administration. The aftermath of the December 2014 opening to Cuba: more violence against activists, U.S. diplomats suffering brain damage in Havana under suspicious circumstances, the seizure of a U.S. Hellfire missile on its way back to the United States, somehow ended up in Havana, and greater projection of the Cuban military into Venezuela and Nicaragua. And to add insult to injury, Cuban troops on January 2, 2017 chanted that they would shoot President Obama so many times in the head that they would give him a lead hat.

The lessons of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis continue to remain relevant with the regime in Havana, and the failure to follow them can be seen in this recent detente with the Castro regime.

Cuban Studies Institute, October 22, 2020

What We Learned From The Cuban Missile Crisis

By Jaime Suchlicki

United Nations during the Cuban missile crisis

In 1962, the Soviet Union surreptitiously introduced nuclear missiles into Cuba. A surprised, embarrassed, and angry President John F. Kennedy blockaded the island and after eleven tense days the Soviet Union withdrew its missiles.

The crisis, which brought the world to the brink of a nuclear holocaust helped, among other things, to shape the perceptions of American foreign policy leaders toward the Soviet threat and the world. Some of the lessons of that crisis are still with us today.

The first lesson was that there is no substitute for alert and quality intelligence. The United States was surprised by the Soviet gamble, and not until the missiles were in the island and U.S. spy planes had photographed them did the While House discover the magnitude of the challenge and the peril that they represented to U.S. security. While Cubans on the island reported suspicious movement of missiles, U.S. intelligence failed to warn the Kennedy administration in advance of Soviet plans or objectives.

Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro

The second lesson was a heightened awareness about the dangers of nuclear weapons. Following the crisis, the United States, the Soviet Union, and most countries of the world signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. A direct telephone line was installed for communication between the U.S. President and the Soviet leader, and U.S. withdrew some missiles from Turkey and elsewhere.

The third lesson was in management of crises. President Kennedy’s careful moves during those tense 11 days averted a nuclear confrontation. While some in this country advocated an invasion of Cuba and the end of the Castro regime, the President preferred a blockade, and diplomacy and negotiation with the Kremlin. As we have learned since, Fidel Castro called on Khrushchev to launch the missiles from Cuba against the United States, an action that would have surely forced a counter-launch not only against Cuba but also the Soviet Union, causing a major world catastrophe.

The fourth lesson is that weakness on the part of the American leadership, or perception of weakness by enemies of this country, usually encourages those enemies to take daring and reckless actions.

The single most important event encouraging and accelerating Soviet involvement in Cuba was the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961. The U.S. failure to act decisively against Castro gave the Soviets illusions about U.S. determination and interest in the island. The Kremlin leaders believed that further economic and even military involvement in Cuba would not entail any danger to the Soviet Union itself and would not seriously jeopardize U.S.-Soviet relations. This view was further reinforced by President Kennedy’s apologetic attitude concerning the Bay of Pigs invasion and his generally weak performance during his summit meeting with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna in June of 1961.

President Kennedy addressing the nation during the Cuban Missile Crisis

The final and perhaps most important lesson is that there are anti-American leaders in the world willing to die and risk the destruction of their countries in order to fulfill their political ambitions. Castro and Khrushchev belonged to this group–the former because of his Anti-American hatred and his ambition to play a power role beyond the capabilities of his small island, and the latter because of his desire to overcome the U.S. strategic advantage and change the balance of power in the world. Both were willing to take actions that endangered their people as well as the world.

Dangerous and daring leaders, and terrorists, enemies of the United States, remain today in and out of power in many countries. The actions of Castro and Khrushchev in 1962 should give us pause, but little comfort. Not only are nuclear weapons still around, but more ominous chemical and biological weapons have been developed since the missile crisis. The lessons of that crisis and the danger of a difficult world are still with us.

*Jaime Suchlicki is the founder and Director of the Cuban Studies Institute, CSI, a non-profit research group in Coral Gables, FL. He is the author of Cuba: From Columbus to Castro and Beyond, now in its 5th edition; México: From Montezuma to the Rise of the PAN, 2nd edition, and Breve Historia de Cuba. He is a highly regarded consultant to the private and public sectors.

https://cubanstudiesinstitute.us/principal/what-we-learned-from-the-cuban-missile-crisis-2/

The Wall Street Journal, October 23, 2012

Cuban Blackmail, 50 Years After the Missile Crisis

The past decades have shown that the Castro brothers' behavior in October 1962 was perfectly characteristic.

By Jeb Bush and Frank Calzon

Oct. 23, 2012 7:16 p.m. ET

With this week marking the 50th anniversary of the Cuban missile crisis, Americans are recalling the 13 days in October 1962 when the Soviet Union and Cuba's Fidel Castro brought the world to the brink of nuclear Armageddon.

But in assessing the crisis, and President John F. Kennedy's decisions over those 13 days, it is equally important to consider what has happened since. Using what the late U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick called the "politics of deception," Cuba's Castro brothers have maintained power through international deceit, blackmail and hostage-taking.

The past decades have shown that the behavior of the Castro brothers in 1962 was perfectly characteristic. Fidel Castro has never shied away from a political gamble such as deploying secret Soviet missiles and then lying about them. He assured other governments that he would never do such a thing, just as the Soviet Union's ambassador to the United States told the Kennedy administration that rumors about missiles were false. But the missiles were there, and their deployment was an effort to intimidate and blackmail America.

Today, Havana's intimidation and blackmail are of a different magnitude, but there are plenty of examples.

Days ago, a Cuban court sentenced young Spanish politician Angel Carromero to four years in prison for committing manslaughter in the death of Oswaldo Payá, one of Cuba's most prominent human rights leaders. Payá died while a passenger in a car Mr. Carromero was driving, when it veered off the road and hit a tree under suspicious circumstances. Payá's family says that Mr. Carromero has sent text messages saying that a vehicle (presumably driven by Cuba's state security police) was attempting to force him off the road. The family was prevented from attending the trial and is calling for an international investigation.

For years, state security had tried to intimidate Payá and his foreign visitors, part of a larger effort to discourage democracy advocates from visiting or contacting Cuban dissidents. Havana similarly tries to intimidate other countries—such as Spain, whose nationals have business interests in Cuba—into accepting its routine violations of human rights, including the beatings of dissidents.

Joining Mr. Carromero as a hostage in Cuba is Alan Gross, an American development worker held since December 2009. His supposed crime: giving a laptop computer and satellite telephone to a group of Cuban Jews.

Mr. Gross has lost some 100 pounds in prison, according to his wife, who also reports that he has a growth on his shoulder that may be cancerous. The Castro regime intends to keep him in prison until the U.S. government releases five Cuban spies from prison in the U.S.

There is a long history here. In 1962, Fidel Castro wrung $53 million from Washington in exchange for releasing the prisoners he had taken after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Before that, during the guerrilla war against the Batista dictatorship, Raúl Castro extorted thousands of dollars from owners of sugar mills, threatening to burn down their homes and mills unless they aided the guerrillas. In June 1958, he tried to force negotiations with Washington by kidnapping 29 American sailors and marines; when word got out that Washington might send U.S. Marines to rescue the hostages, the Castros freed them.

In dealing with Cuba's regime, the Obama administration has too often sent contradictory signals of U.S. resolve. Though Raúl Castro (who now heads the Cuban government) has refused to allow Mr. Gross to return to the U.S. to visit his seriously ill mother, the Obama administration allowed a Cuban spy to leave an American halfway house to visit his sick mother. While Mr. Gross remains in prison, the Obama administration last year issued visas to Raúl Castro's daughter and her retinue so they could visit America and attack its Cuba policy.

The lessons of October 1962 must not be forgotten. President Kennedy showed fortitude and resolve in forcing the Soviet Union to stand down. Whoever wins the Nov. 6 election ought to deal similarly with today's intimidation and deception from the Castro regime.

Mr. Bush is a former governor of Florida. Mr. Calzon is executive director of the Center for a Free Cuba in Washington, D.C.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970203406404578070462956566472

John F. Kennedy Library, October 14, 2012

50th Anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis

October 14, 2012

[Excerpt]

MARY SAROTTE: I’d like to go over to Brian, who in a previous life before he became an author and started teaching at the University of Miami, was the principal Cuban analyst for the CIA and spent a great deal of his life thinking about what Castro was doing, Castro’s motives. So I’d be interested in what you believe Castro’s motives were in this crisis and what he viewed as the important points in its unfolding?

BRIAN LATELL: Mary, Castro, in one of his recollections about the crisis, said that those days, his guerrilla instincts all came back to the fore. He was in the mood of a warrior. He was militant. He was idiosyncratic, and he was volatile. As Khrushchev and Kennedy were struggling during those last few days to resolve the crisis without resorting to war, Fidel Castro was stimulating military conflict. Castro, on the morning of October 27th -- “Black Saturday” that we keep hearing about, the worst, the most dangerous, the most tense day of the Missile Crisis -- Fidel Castro ordered all of his artillery to begin firing on American reconnaissance aircraft at dawn, at sunrise that morning of “Black Saturday.”

Fidel Castro said later on the record, “War began in those moments.” And the commander, one of the Soviet generals there with the expeditionary force, General Gribkov, said essentially the same thing. He said that, “We Soviet commanders, all the way from the generals down to the lieutenants in the Soviet force, we all agreed that conflict, military conflict, essentially began that morning.” October 27th, “Black Saturday,” Kennedy and Khrushchev are desperately trying to bring this crisis to a peaceful end, and Castro is stoking the fan of conflict.

Fidel Castro was so persuasive with his Soviet military counterparts that later that day, “Black Saturday,” the U-2 was shot down. We saw earlier in the video that the U-2 was shot down. It’s very interesting. Nikita Khrushchev believed, I think until his death, that Fidel Castro had personally ordered the shoot-down by a Soviet ground-to-air missile site, Khrushchev believed that Castro had actually somehow been responsible for it himself. Apparently, he was not. It was a Soviet commander who actually gave the order to fire the missile. But it was in the spirit of joint conflict. The Soviet military and the Cuban military were now essentially resisting the Americans as one.

General Gribkov said that, “It was amazing that we were prepared, we, Soviet forces” -- including himself, the general -- “if the Americans invaded, we were prepared to fight as hard as we could and then to go into the mountains of Cuba, and to fight to the death as guerillas with our Cuban comrades.” This was a Soviet general who said that.

Arthur Schlesinger I think summed it up very nicely in something that he wrote later. He said that psychologically, by “Black Saturday,” psychologically Fidel Castro had come to dominate most of the Soviet leadership in Cuba. Fidel was that persuasive, that mesmerizing. He was that much of a role model, a revolutionary role model to the Soviets, that they were beginning to follow his bidding, if not his actual orders.

Gribkov, the general, said, “We were inspired, we were imbued by Fidel Castro’s revolutionary legitimacy.” So Castro ordered the first shots that were fired, the aircraft barrages on the American aircraft. He was partly responsible, he later admitted, for the shoot-down of the U-2.

And later on the evening of “Black Saturday,” he wrote what is commonly known as the “Armageddon letter” to Khrushchev. He went to the Soviet embassy in Havana late that night, October – well, he actually went on the 26th, the night of the 26th, and he was there until dawn the next day, the 27th, he dictated a letter. It was an apocalyptic letter. It’s commonly called the “Armageddon letter.” And he recommended to Khrushchev that if Cuba is invaded by the Americans, Khrushchev should not hesitate but to launch a preemptive nuclear attack on American targets.

Now, I don’t think that Castro was irrational. I think he was wildly idiosyncratic. I think it was bizarre, but I don’t think it was totally irrational. He knew that the tactical nuclear weapons were on the ground in Cuba. He really wanted those weapons. He later said, “Had I been in charge, and if the Americans had invaded, I would’ve ordered the tactical nuclear weapons fired on American invading forces.” So Castro’s “Armageddon letter” to Khrushchev recommending a first preemptive nuclear strike on the United States apparently assumed that when the Americans invade, nuclear weapons are going to be fired on the battlefield. The Soviet Union, the Soviet general staff, should not wait after those weapons are fired for an American nuclear, a strategic nuclear assault, on Soviet military and civilian targets. That was Fidel Castro. He came to dominate the Missile Crisis during its final, essentially its final day, “Black Saturday.”

[ Full Transcript ]

The New York Times, September 21, 2009

Details Emerge of Cold War Nuclear Threat by Cuba

In the early 1980s, according to newly released documents, Fidel Castro was suggesting a Soviet nuclear strike against the United States, until Moscow dissuaded him by patiently explaining how the radioactive cloud resulting from such a strike would also devastate Cuba.

The cold war was then in one of its chilliest phases. President Ronald Reagan had begun a trillion-dollar arms buildup, called the Soviet Union “an evil empire” and ordered scores of atomic detonations under the Nevada desert as a means of developing new arms. Some Reagan aides talked of fighting and winning a nuclear war.

Dozens of books warned that Reagan’s policies threatened to end most life on earth. In June 1982, a million protesters gathered in Central Park.

Barack Obama, then an undergraduate at Columbia University, worried about the nuclear threat and later wrote as a student and a journalist about ways to avoid global annihilation.

The future president didn’t know half the danger.

The National Security Archive, a private research group at George Washington University, recently made public documents that reveal the nuclear threat in new detail. The two-volume study, “Soviet Intentions 1965-1985,” was prepared in 1995 by a Pentagon contractor and based on extensive interviewing of former top Soviet military officials.

It took the security archive two years to get the Pentagon to release the study. Censors excised a few sections on nuclear tests and weapon effects, and the archive recently posted the redacted study on its Web site.

The Pentagon study attributes the Cuba revelation to Andrian A. Danilevich, a Soviet general staff officer from 1964 to ’90 and director of the staff officers who wrote the Soviet Union’s final reference guide on strategic and nuclear planning.

In the early 1980s, the study quotes him as saying that Mr. Castro “pressed hard for a tougher Soviet line against the U.S. up to and including possible nuclear strikes.”

The general staff, General Danilevich continued, “had to actively disabuse him of this view by spelling out the ecological consequences for Cuba of a Soviet strike against the U.S.”

That information, the general concluded, “changed Castro’s positions considerably.”

Moscow’s effort to enlighten Mr. Castro to the innate messiness of nuclear warfare is among a number of disclosures in the Pentagon study. Other findings in the study include how the Soviets strove for nuclear superiority but “understood the devastating consequences of nuclear war” and believed that the use of nuclear weapons had to be avoided “at all costs.”

The study includes a sharp critique of American analyses of Soviet intentions, saying the Pentagon tended to err “on the side of overestimating Soviet aggressiveness.”

Letter taken from the Wilson Center

October 26, 1962

TELEGRAM FROM FIDEL CASTRO TO N. S. KHRUSHCHEV

Dear Comrade KHRUSHCHEV,

In analyzing the situation that has arisen through the information at our disposal, it seems that aggression in the next 24 to 72 hours is almost inevitable.

Two variants of this aggression are possible:

1. The most likely one is an air attack on certain installations, with the aim of destroying those installations.

2. A less likely, but still possible variant is a direct invasion of the country. I believe that the realization of this variant would require large forces, and that this may hold the aggressors back; moreover such an aggression would be met with indignation by global public opinion.

You can be sure that we will offer strong and decisive resistance to whatever form this aggression may take.

The morale of the Cuban people is exceptionally high, and will face the aggression heroically.

Now I would like to express in a few words my deeply personal opinion on the events which are now occurring.

If an aggression of the second variant occurs, and the imperialists attack Cuba with the aim of occupying it, then the danger posed by such an aggressive measure will be so immense for all humanity that the Soviet Union will in circumstances be able to allow it, or to permit the creation of conditions in which the imperialists might initiate a nuclear strike against the USSR as well.

I say this because I believe that the aggressiveness of the imperialists is becoming extremely dangerous.

If they initiate an attack on Cuba -- a barbaric, illegal, and amoral act-- then in those circumstances the moment would be right for considering the elimination of such a danger, claiming the lawful right to self-defense. However difficult and horrifying this decision may be, there is, I believe, no other recourse. This opinion of mine has been formed by the emergence of an aggressive policy in which the imperialists ignore not only public opinion but all principles and rights as well: they blockade the sea, they violate air space, they are preparing an attack, and moreover they are destroying all possibilities for negotiations, even though they are aware of the gravity of the consequences.

You have been and remain a tireless defender of peace, and I understand how difficult these hours are for you, when the results of your superhuman efforts in the struggle for peace are so gravely threatened.

However, we will keep hoping up to the last minute that peace will be maintained, and we will do everything in our power to pursue this aim, but at the same time -we are realistically evaluating the situation, and are ready and resolved to face any ordeal.

I once again express our whole country’s endless gratitude to the Soviet people, who have shown such brotherly generosity towards us. We also express our admiration and deep thanks to you personally, and wish you success in your immense and crucial endeavor.

With brotherly greetings,

FIDEL CASTRO. "